Myanmar has seen the back of the sixth Special Envoy of the Secretary General of the United Nations since 1995. Noeleen Heyzer resigned her position in recent weeks, earlier than planned from her appointment in October 2021 and assuming her role in December of that year.

What will be her legacy? Not much. A kind assessment could conclude she gave it the good old college try, but was reasoning with caged beasts. A realpolitik regard would argue she was doomed from the starting line, because those caged beasts cannot be reasoned with.

What can we learn from Heyzer’s 20 months in the position? There isn’t much to labor over. The military State Administration Council (SAC) wasn’t interested in any form of international engagement let alone mediation, and absolutely nothing to do with conflict resolution. The efforts of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) have been stuck since the signing of the Five-Point Consensus in early 2021, yet remain the lodestar of international efforts regardless of how adrift, capsized or sunk they are. Heyzer didn’t have much to work with.

The entire “good offices” position of the envoy is mired in the past, with its mandate in the UN General Assembly, not completely with the Secretary General. There hasn’t been any serious reform of the role in close to 30 years, a point acknowledged by an in-depth study of the good offices mandate released by the International Peace Academy (IPI) over 10 years ago.

One of the concluding points of that study from 2012 could have been written today: “There is no doubt that the UN carries a legacy of resentment or disappointment among many sides within Myanmar who have felt, for different reasons, that the good offices in the past did not sufficiently consider their interests. In the international donor community, while some acknowledge the potentially important role the UN can play in Myanmar, few seem to want the world organization to actually take the lead in coordinating international assistance to the country.” The failure of the UN to gain access to Cyclone Mocha-affected communities in Rakhine State, or conflict-affected displaced in Sagaing Region, poses crucially important questions on the efficacy of the UN to remain in Myanmar.

With a weak and distracted Secretary General in António Guterres, a dysfunctional Permanent Five members of a divided Security Council (China, Russia, the United States, Britain and France), it’s a wonder Heyzer got any attention let alone the level of support she needed from her first day.

Early on, she was roundly criticized for suggesting a form of “power sharing” in a Channel News Asia interview. Whether she misspoke or considered it a serious proposal and was compelled to walk it back following the furor, the damage of an unforced error was already inflicted. Her one trip to call on Min Aung Hlaing in August 2022 was an unmitigated disaster, with the SAC releasing details of their conversation that were not completely congruent with what her post-visit statement said.

Following this envoy equivalent of road-kill, she was compelled to broaden her consultations to members of the resistance including the National Unity Government (NUG) and some ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), although this was an uncommon development. From the August visit until her resignation, she was dogged by criticism from all sides, much of it perhaps unfair yet reflecting frustration at ongoing violence and the trap of diplomatic language that compelled her to express “deep concern” at incessant SAC mass atrocities.

Heyzer met with Chinese foreign minister Qin Gang on May 1, where he “stressed the need to act prudently and pragmatically to prevent the escalation of the conflict and spillover of the crisis, and expressed his hope that Madame Special Envoy will uphold an objective and fair position and play a role as a bridge.” Trips were also made to India, and all around Southeast Asia. Soon after the announcement of her stepping down, she visited with NUG Foreign Minister Daw Zin Mar Aung: a photo of them hugging was both touching and, one hopes, cardiac arrest-inducing in Naypyitaw.

The Global New Light of Myanmar made its position on the UN clear in its June 16 opinion piece from Kyaw Myint Tun-Paris called “The Picture of Irrelevance.” It was vintage vitriol. While it may have been designed to condemn the UN system and international mediation efforts, it must also be seen as a good riddance to Heyzer and a glove slap to any replacement.

“What breakthrough do they have to prove in recent memory? Where have they brought lasting peace? Name one! Under their watch record number of people have been forcibly displaced or stateless. So, what have they done? Is the world becoming more peaceful? These people should be given no role in finding solutions for the problems Myanmar is facing. Solutions for Myanmar will come from within and with the help, cooperation and understanding of the neighbours (sic) and friendly countries.” As if to pour salt on the wound, the paper also carried a report on a meeting with acting UN Resident Coordinator Ramanathan Balakrishnan and colleagues with three SAC ministers in Sittwe, still struggling for official access to assist over a month after Cyclone Mocha.

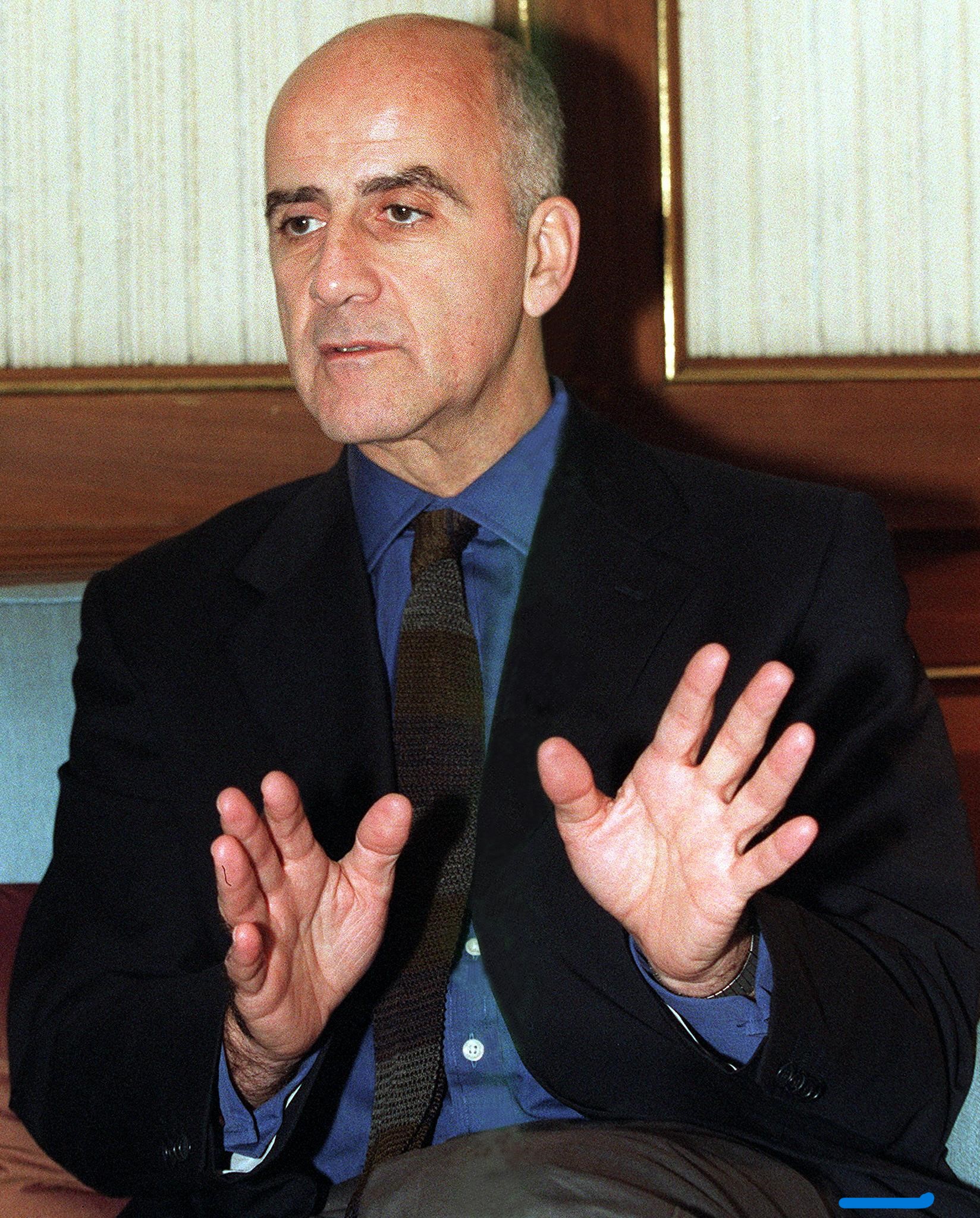

What have we learned from the near three decades of special envoys? Precious little. The first, the polished Peruvian diplomat Álvaro de Soto served from 1995 to 1999, which started optimistically with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s release before dissolving into repressive military rule deadlock. He may have visited the country six times during his tenure, but he achieved little of note apart from the “concession” of meeting with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi on every visit.

De Soto’s contribution to Myanmar may be slight, but his legacy as a UNSG special envoy is instructive for Myanmar. Resigning from his envoy role in the Middle East peace process, his frustration at being hogtied to conditions that limited engagement with key actors was reflected in his leaked End of Mission memo in May 2007 following his resignation: “the UN should resist the natural temptation of almost every government and intergovernmental institution to throw a committee or a czar, or in this case, an envoy, at a problem…(w)e are not in the lead, and the role we play is subsidiary at best, dangerous at worst.” A similar end of mission memo from Heyzer should be encouraged.

Then the reptilian Razali Ismael from Malaysia (2000-2005) served at a relatively optimistic time following the release of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi in 2002, but any optimism was dashed with the mass killing of her supporters at Depayin in May 2003, and then the purge of his erstwhile partner, Military Intelligence chief and Prime Minister General Khin Nyunt in October 2004. He refused to renew his position in early 2006 because he had been not permitted to visit the country in two years.

In a creepy two-step criticism of the then regime with pretension over his own performance, Razali said in an interview; “Progress has not been made towards any reconciliation. If there used to be any, that has now snapped with [Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s] continued house arrest… What possibility is there of further progress?… Still, there is no frustration as this was, after all, a noble effort… good at dodging things and stonewalling… We have been dealing with these [Myanmar military] people for a very long time now. We are familiar with their ways.” This wasn’t exactly an advertisement for institutional memory and adaptive engagement.

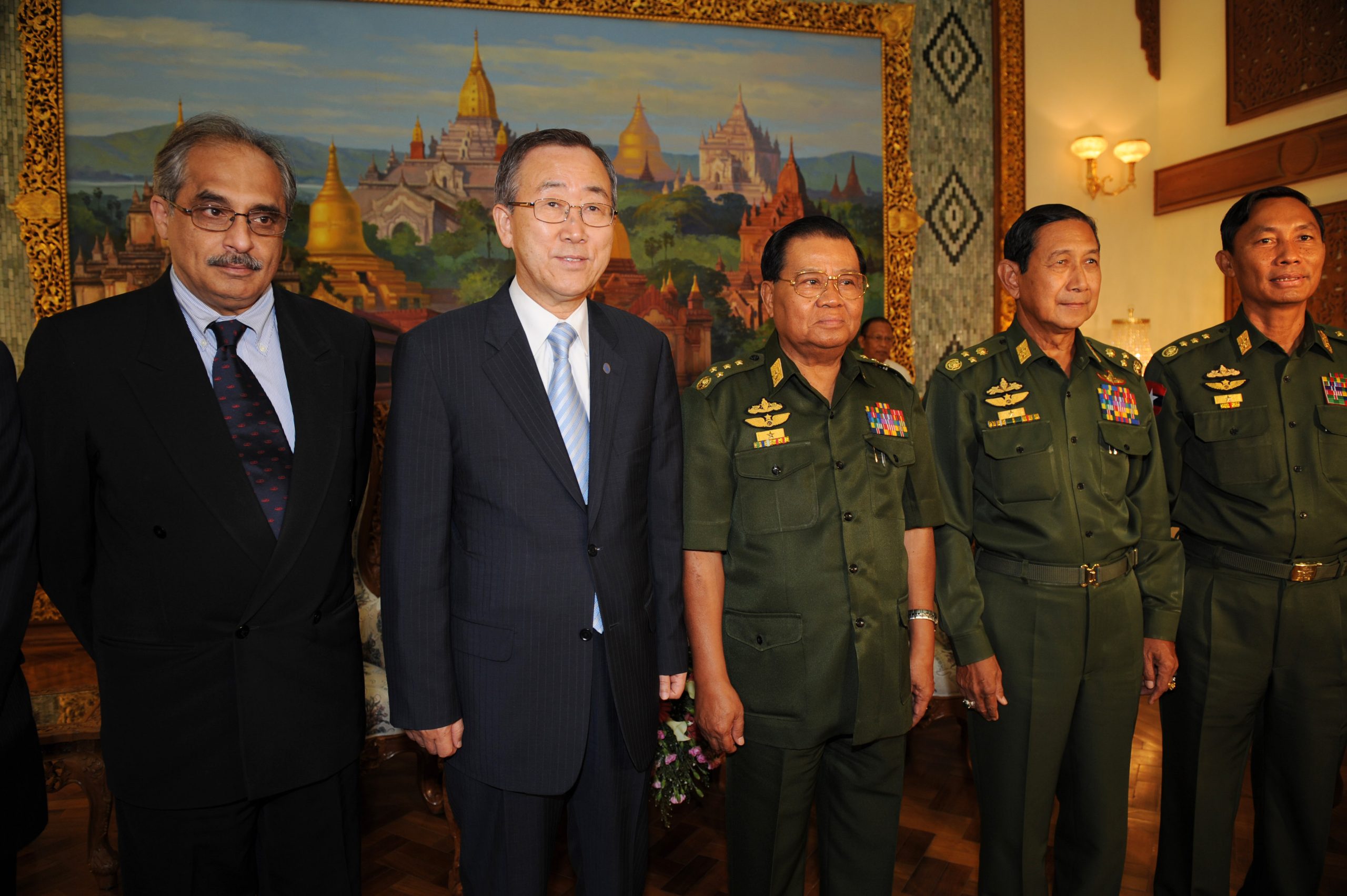

Next came the former Nigerian ambassador to the United Nations, Ibrahim Gambari. The then ruling State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) should have recognized a kindred spirit in Gambari, after all he rebuffed the General Assembly when they condemned the execution of prominent environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight other Ogani people in late 1995. Gambari faced a genuine domestic political deadlock in 2006, then the popular protests and the brutal crackdown of September 2007, Cyclone Nargis and the desperate days of the UN seeking access to affected areas and the timely visit of Ban Ki-moon (who visited again in April, with great fanfare and no progress).

The Indian diplomat Vijay Nambiar enjoyed greater success, but he operated between 2010 and 2016 when the opening afforded him access, and even some EAOs welcomed his role in the peace process. Nambiar wasn’t completely astute: he asked Senior General Min Aung Hlaing to contribute Sit-Tat troops for UN peacekeeping operations in 2014 (a small number served in Liberia and South Sudan).

Christine Schraner Burgener was appointed in April 2018 following the carnage of ethnic cleansing against the Rohingya in Rakhine State, was told by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to stay out of the peace process and stick to Rakhine, where she could do little. Her post-2021 performance was strident in condemning the SAC, her calls with Vice Senior General Soe Win unresponsive, and her plaintive calls to visit Myanmar rebuffed by the SAC, but also over-stating her importance: “Clearly, I can imagine that he [Min Aung Hlaing] would not like to see me now in Myanmar because the people know me… and they would probably be very encouraged by my presence.” Despite pushing a much stiffer and determined UN response for an envoy, she was also criticized in Myanmar for perceived moral equivalency in condemning violence by all sides (the trap of neutrality in vocalizing opposition to violence, even grossly asymmetric state violence and atrocity).

Kyaw Myint Tun-Paris summed up the past envoys in colorful fashion. “There have been appointments of those who were no longer wanted anymore close to the Ivory Tower in New York. Dump them all on Myanmar! There was one who was appointed so that frequent trips can be made to see family and relatives in a nearby country [likely Gambari]. Then, there was a lightweight who had no clues whatsoever about Myanmar [this could be any of them]. One promptly turned up at Davos soon after the appointment… Whether there is a need or not, they visit the country frequently and put out press statements just to show they are working hard and justify their employment. Attempts would be made to visit the country especially when their contract is up for extension.”

Like carrion birds, potential replacements are circling. But any future appointment will face not just the same blend of SAC stonewalling or UN dysfunction Heyzer endured, but a witches brew of competitive engagement initiatives from predatory actors from China, India, Thailand and Japan through the Nippon Foundation, along with the frozen efforts of ASEAN, and the rumors of attempts from Switzerland, Norway, Finland and other deluded European states looking to forge a breakthrough. The competing “Track 1.5” efforts of Thailand has annoyed Indonesia, received no support from the rest of ASEAN, and is but the latest data point of dysfunction. Many of these efforts have some bit-part Myanmar players who have highly questionable legitimacy and political cachet. All of this incoherence benefits the SAC, who chortle at foreigners competing for pole position to appease them.

For many in the international community have adopted a stance of mee-sa-ta-phet yay-mote-ta phet (holding the flame/torch in one hand and the firehouse in the other): effectively hedging their bets on who is going to “win” the conflict and be the side to ingratiate. There has been a plethora of post-coup shapeshifting amongst foreign actors, who prior to February 2021 sought to engage the Myanmar deep state and its many war criminals, and who—regardless of their affected ardor for the resistance now—will casually betray the revolution when the winds of opportunism shift.

If another envoy is going to be offloaded on Myanmar, it will likely be another seasoned diplomat with similar skills sets to Heyzer. The candidates will resemble archetypes of international servants, but to the SAC a bevy of min-laung (pretender kings, or more accurately “imminent kings”) and their cohorts of pontificating min-sayar (king’s teacher, or advisor). There will be no “innovation”, “off-ramping”, “nuance”, or that absolute pearl of statecraft thinking, “fresh approach.” It’s almost certainly going to be some soiled version of what came before.

But does it need to be? Is there a possibility of obviously needed reform? Ralph Waldo Emmerson wrote that “foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of small minds, adored by little statesmen”, which could aptly describe the current cohort of Western diplomats and donors working on Myanmar all conjoined by a dearth of clear thinking.

There are four potential courses of action: in theory. In all likelihood the UN and P5 countries will shuffle on with an utter disregard for impact, progress or the interests of the people of Myanmar. But what if we entertain the potential for the self-straitjacketed global order to react differently, even with expectations on progress being as low as possible?

First, consider a completely different candidate. Heyzer was deemed suitable in late 2021 because she was a consummate UN insider, who had sidled up to the generals before, and being Singaporean could “read their minds” more acutely. Many observers thought then as now, these qualities worked against her. The same calculation holds true. If you find merely a “new Noeleen” then we’ll all be concluding similar bleak assessments of dashed expectations in three years as we are today. Six very different envoys from Africa, Southeast Asia, Switzerland and Latin America have confounded calculations on whether outsiders or Asians are most effective. No one who actually wants the job should be considered, especially if it’s former US ambassador to the UN Bill Richardson or disgraced British politician Boris Johnson, should they put their hands up. A UN lifer obviously has little comparative advantage other than a more acute understanding of the UN’s internal defects, as Heyzer demonstrated (as did previous envoys). Former military officers elicit little respect either, as retired US general Wesley Clark found in 2010 when he co-chaired an Asia Society task force on engaging Myanmar, or most recently the lack of any discernable progress in engaging with the SAC from former Indonesian army general Agus Widjojo.

Second, rewire an entirely new approach, with a new mandate directly from the Secretary General and a closer rapport with the SG’s office. The need for reform has been apparent for many years, but even tinkering with structures in the UN is seen as disruptive. If Heyzer’s failure should spur anything, it is the necessity for a genuine reimagining of the role, and what its long-term utility could be for the UN’s assistance to Myanmar. One dimension could be the total restructuring of the UN’s presence in Myanmar, discarding half of the operational agencies and paring down presence and operations to address immediate humanitarian and development needs related to livelihoods, health, education and emergency relief. This would alleviate the funding gap for donors who have already invested in multi-donor funds. The current leadership under Ramanathan Balakrishan needs to be radically reconstituted, and a balance sought between operational realities and high-level mediation efforts.

Third, consider a collective effort of a contact group of multiple officials, expanding the team from a bare bones operation (although one I’m certain well remunerates the players regardless of their 1-0 scorecard) to multiple high-level actors. Nothing limply ineffectual like the “Group of Friends of Myanmar” that the UN tried before, following the 2007 demonstrations and crackdown, involving some 14 countries. However, this shouldn’t be a consortium of existing envoys or point people such as the Norwegian envoy, or Igor Driesmans, the European Union envoy, but a group of higher level officials who can interact with multiple actors.

These consultations must be broad and inclusive, especially the resistance actors in EAOs, the NUG and emerging political forces such as the Karenni State Interim Executive Council (IEC) and new configurations such as the Sagaing Forum. However, just the convening of such a forum within the constraints of the UN is devilishly difficult with protocol, egos and above all competing state interests. Look at one collection of “Group of Friends” meeting memos from 2009, which echoes the impasse of 2023, and face up to the hard facts that change in Myanmar didn’t come about from outside pressure or support.

Or, fourth, do nothing. Just inform the SAC that they’re not worth the trouble. Alleviate the diplomatic corps from having to expend energy on supporting labored interventions that have no chance of even minimal success. Clear the space for ASEAN to continue to fail. Stop investing in false hope in Myanmar; it might do the standing of the UN some good, but likely not.

The Heyzer maneuver of early departure should be a call for reform and reengagement, to clear a clogged diplomatic passage. But it won’t be.

David Scott Mathieson is an independent analyst working on conflict, humanitarian and human rights on Myanmar.