Amidst the unrelenting horrors of Rakhine state and the conflagration of Buthidaung, heavy airstrikes in Magwe and Sagaing, and the grim milestone of over three million people internally displaced in Myanmar, it may have gone unnoticed that this is the United Nations Protection of Civilians (PoC) Week, May 20-24. A number of events are being held, including debates in the UN Security Council (UNSC) and the release of the annual report of Secretary-General António Guterres on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict.

Also being rolled out this year is the latest UN Agenda for Protection, released in February to roughly coincide with the 75th Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights released in December 1948. Are all of these efforts seriously committed to dousing a world on fire? From Myanmar, to Gaza, South Sudan, the Congo, and many other armed conflicts the ability of world bodies to protect civilians is seemingly incapacitated. Or are this week’s activities, in elite settings in foreign capitals with few civilians needing protection in attendance, just the international community, especially the UN, simply fiddling while Rome burns?

The new agenda is marking another two key milestones. The first is the 25th anniversary of Security Council Resolution 1265, the first of its kind to address protection of civilians in armed conflict, which stated: “the need to address the causes of armed conflict in a comprehensive manner in order to enhance the protection of civilians on a long term basis, including by promoting economic growth, poverty eradication, sustainable development, national reconciliation, good governance, democracy, the rule of law and respect for and protection of human rights.” Since then, the UNSC has passed more than 12 resolutions on various aspects of PoC, including attacks on people living with disabilities, healthcare workers, aid workers, journalists, missing persons, food security, and in April 2014 called on states to “prevent and fight against genocide” (UNSC 2150).

The second milestone is the 75th anniversary of the four Geneva Conventions of 1949, the motto of which is “The One Set of Rules We All Agree On.” If it were only that straightforward. Protection of civilians and respect for International Humanitarian Law (IHL) is under threat more intensively than any time in the past two decades. What do all of these activities this week actually mean for the lives of civilians in Myanmar?

The protection pantomime

As the new agenda document states, drawing on case studies of past UN failings, respect for human rights is a critical component of peacebuilding, yet “we need to recognize that, in places like Rwanda, Srebrenica, Sri Lanka and Myanmar, we have not consistently been able to meet these expectations and may not have done everything possible to protect people, with disastrous consequences for people’s lives. This has undermined the UN’s reputation and legitimacy.” The UN’s scriptwriters are nothing if not masters of understatement. Over the past several years, in Myanmar if nowhere else, the UN’s commitment to protection, peace, and human rights has deteriorated to the point of insult whenever these terms are bandied about.

Peppered throughout the document is the contention that “people must be at the center of our protection response.” This is a laudable commitment, but what does it mean? The UN claims “full and meaningful participation by all those affected, including women, children, minorities and indigenous peoples, refugees and displaced persons, migrants, people with disabilities, and others, in shaping and implementing the UN’s protection work.” Yet in few cases is any participation full or meaningful; in fact, in Myanmar, public participation is often predicated on servility, subservience, quiescence, and systematic marginalization.

And that is just the UN’s national staff. If you’re a civilian from, say, Salingyi or Kyainseikgyi, the UN is often an abstraction if known at all. But there are multiple shades of exposure to the UN and the broader interpretations of what they actually accomplish. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) is often presented as the standard bearer of protection, the noble guardian of human rights promotion. But if you’re a farmer in Sagaing enduring temperatures of 48 degrees Celsius, a United Nations Development Program (UNDP) Dry Zone water pond recovery project may be more directly pertinent to your protection than a ponderous report to the Human Rights Council (HRC) in Geneva.

Some of the work of other Yangon-based agencies, from food, children to health, will likely make a more prodigious impact on civilian protection in Myanmar than this week’s elite events in Geneva and New York. This doesn’t absolve the UN from its profligate waste, corruption, nepotism, and predilection for authoritarian regimes and the cold comfort of stable “presence” it brings. But it does broaden the concept of protection to include development, as reflected in various UNSC resolutions, including last year’s PoC report’s emphasis on the right to water.

This year’s report of the Secretary-General on protection of civilians in armed conflict is both a horrific indictment of the state of war and destruction in the world, but also the callow methods of the UN in discussing it. The countries mentioned include the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali, Mozambique, Somalia, South Sudan, the Sudan and of course Gaza and Ukraine as well as Myanmar. The report is a tableau of civilian suffering that lays bare the failure of the international system to ensure peace and respect for human rights. Special emphasis was also placed on the effects of Explosive Weapons in Populated Areas (EWIPA), which are increasingly relevant to the dynamics of armed conflict in Myanmar as fighting reaches more and more urban spaces.

But the tone of the report is bureaucratic, at odds with its subject matter. “If one imagines the full protection of civilians as lying at one end of a spectrum of protection, important waypoints already exist along that spectrum, not least full compliance with international humanitarian law. However, additional waypoints that move us closer towards the full protection of civilians are emerging at the global, regional and national levels and can be further built and expanded upon.” This is essentially a meaningless assortment of words, and like so many UN documents it is inward, and process and protocol-oriented, which is ultimately dehumanizing.

International human rights and humanitarian groups may speak in stronger language than the UN, but they too are often complicit in the protection racket. Twenty organizations, including Save the Children, the Norwegian Refugee Council (RC) and Amnesty International signed a statement as the NGO Working Group on the Protection of Civilians marking PoC Week that made this warning: “We are standing at the threshold, witnessing a deliberate undermining of the collective commitments established to limit the barbarity of war, combined with a lack of accountability when international laws and standards are disregarded. In addition, survivors are often left without justice or redress. If this accountability gap is not addressed urgently, we risk barrelling further down a path of no return.”

In Myanmar, many INGOs produce internal protection reports that are little more than news summaries interspersed with what activities their agencies were able to deliver. How much donor funding goes to protection activities that are duplicative, wasteful of resources, and achieve absolutely no protection for civilians at all? For many agencies, protection is an often tacked-on activity, and efficacy is barely considered. How about displaying all the separate “protection” reports produced by various UN agencies and INGOs on a quarterly basis then calculating what actual impact that resulted in civilians being protected actually occurred? In a data-saturated humanitarian sector, that is one metric that few people want to see.

The new agenda for protection also demonstrates the capacity of the international system to routinely reinvent its conscience. Before the new permutation of the protection racket, it was Ban Ki-moon’s Human Rights Up Front (HRUF) initiative, which evolved from the 2012 Petrie Report on the UN’s systemic failures in the final stage of the Sri Lankan civil war in 2019, in which over 40,000 civilians were slaughtered. HRUF was finalized in 2014, just in time for the UN to utterly fail in response to ethnic cleansing against the Rohingya a few years later.

Myanmar was meant to be a key country for mainstreaming HRUF. Five years later, and following the 2017 ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya, the Rosenthal Report laid bare the systemic failings of the UN in Myanmar between 2010 and 2018. The new agenda is partly the product of the Rosenthal report, which found multiple UN dysfunctions, especially tensions between the pillars of the organization and how much to include human rights promotion. This in itself is astonishing: isn’t protection meant to be a core concern? Hardly. Remember what came before HRUF, nearly 20 years ago: Responsibility to Protect (R2P).

IHL and hegemony

At its core, the new agenda and the protection racket writ large is the promotion of IHL and international human rights law (IHRL). In an age of mass atrocity in Gaza, where the United States has armed and enabled Israeli airstrikes that have killed early 40,000 civilians, promoting international law seems not simply selectively hypocritical, but callous. Myanmar has been subject to intensive application of international law for several years, and has an ongoing case to determine possible breaches of the Genocide Convention at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) since 2019, an International Criminal Court (ICC) investigation of the crime of forced deportation, and of course the Independent Investigative Mechanism on Myanmar (IIMM). While the IIMM has been collecting evidence for future prosecutions, it recently released two public reports on hate speech, and gender and sexuality-based violence that were a welcome addition to public knowledge.

Yet justice for multiple victims, old and recent, seems elusive, and the promise of IHL in Myanmar is lamentably fading. There have been three years of impunity for grave crimes, most egregiously by the military council, but also increasingly by revolutionary forces at multiple sites. Even progressive political movements in Myanmar committed to human rights and accountability have all but abandoned faith in the international system of protection. The Israeli military assault on Gaza, and the support from the United States, must be a low point in the 25 years of PoC.

As Perry Anderson wrote in his essay “The Standard of Civilization” in the New Left Review in late-2023, before the Hamas slaughter of civilians was staged in all its death-cult fury, “on any realistic assessment, international law is neither truthfully international nor genuinely law. That, however, does not mean it is not a force to be reckoned with. It is a major one … as an ideological force in the world at the service of the hegemon and its allies.” In other words, it is a Euro-American, or Western construct often used to condemn others and to be rebuffed when it applies to you.

This is no better underscored than in the letter sent to ICC prosecutor Karim Khan by 12 US senators in April, including the great defender of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the Rohingya, Kentucky Senator Mitch McConnell, and ultra-rightwing senators Tom Cotton, Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio, decrying reports that the court would issue an arrest order for Benjamin Netanyahu. It included some extraordinary threats, which no one genuinely committed to justice of any kind would issue. “The United States will not tolerate politicized attacks by the ICC on our allies. Target Israel and we will target you. If you move forward with the measures indicated in the report, we will move to end all American support for the ICC, sanction your employees and associates, and bar you and your families from the United States. You have been warned.”

‘You have been warned.’ McConnell has over the years issued similar threats to Myanmar military leaders, who deserved them far more than Karim Khan, but there wasn’t much follow-through. If the international rules-based order and commitment to IHL was in tatters before Gaza, it’s in shreds now. But Khan called the senators bluff, issuing arrest warrants for Netanyahu and Israeli defense minister Yoav Gallant and Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar. US President Joe Biden called the decision “outrageous.” Regardless of what stance one takes on the conflict in the Middle East, this decision establishes that international law can, and should, be applicable to any party accused of war crimes.

Yet it’s cold comfort to the victims of air strikes in Gaza and Myanmar, where IHL fails to provide any protection other than the slim possibility of justice years in the future. It should also remind all recipients of US assistance that American support for justice is always a calculation of interests, not values.

Localized civilian protection strategies

So how should civilians in Myanmar mark Protection of Civilians Week? Probably not at all. But it does raise the necessity of relocating the frontline of protection work from UN talk-shops back to the communities caught in conflict. In many respects this has already been well underway for several years as part of the broader “localization” push presented at the World Humanitarian Summit in 2016. Yet many community-based organizations (CSOs), local human rights defenders, women’s rights organizations and legal aid groups are well-versed in IHL, IHRL, and protection language and principles.

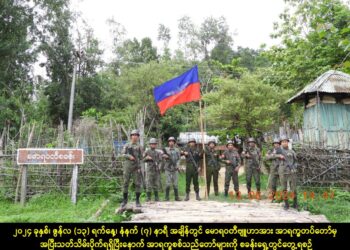

A statement from a recent meeting of some 20 civil society organizations from Karenni State, while recognizing the legitimacy of the Karenni Interim Executive Council (KIEC), contained a series of recommendations to the new governance body and to the “Armed Revolutionary Forces” which called on them to “effectively promote, enforce and adhere to laws of war that emphasize civilian protection cases.” For many revolutionary coalitions or collectives, especially those in Eastern Myanmar, the language of protection is already mainstream. This may not be the case in many parts of the Anya Region where there was historically less exposure to these norms and programming.

Localizing protection will become even more necessary as revolutionary governance structures consolidate in the future: think of “solidarity protection” to support “humanitarian resistance” as Hugo Slim and others have promoted. Local CSOs are generally better placed to advocate for civilian protection norms, access to justice (traditional and legal code) and accountability than elite international efforts increasingly divorced from realities on the ground, in Myanmar and elsewhere. Much of the international humanitarian research on protection stresses “partnerships” with INGOs and the UN, but many of these arrangements are perceived by local actors as unbalanced. Lopsided in terms of risk, financial disbursement, and meaningful participation in project design and leadership.

While some specialized cooperation with international organizations may still be useful in the future, there should ideally be more direct funding to protection activities where it actually matters. There should ideally be a reversal of protection cluster protocols, a decolonization process whereby UN agencies and INGOs are invited as partners not principals.

Essential for “state-based” protection design in the future will be local ceasefire monitoring efforts, which should be designed with core protection principles in place. As the armed revolution will continue for the foreseeable future, local efforts at conflict mitigation, securing vulnerable or at-risk communities and de-escalating conflict will be more effective if led by real protection efforts at a community level. If the UN is serious about placing people at the center of protection, those people who face the effects of armed conflict are the ones who should take the lead, not the purveyors of prolix reports reinventing the language of international failure.

David Scott Mathieson is an independent analyst working on conflict, humanitarian, and human rights issues on Myanmar.