At last month’s UN General Assembly, U Kyaw Tint Swe, Myanmar’s minister for the office of State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, hit out at Bangladesh, blaming the stalled repatriation of Rohingya Muslims on Dhaka’s failure to crack down on a militant group and its supporters, who are actively trying to sabotage the process.

Over 700,000 Rohingya Muslims fled a Myanmar military crackdown in 2017 and are now living in camps in the neighboring country.

Many members of both the Myanmar public and government agreed with U Kyaw Tint Swe’s lambasting of Dhaka on the issue.

“Both the terrorist group ARSA [the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army] and the terrorist insurgent group AA [the Arakan Army] have used Bangladeshi territory as a sanctuary,” he said.

“Efforts to prevent ARSA and its supporters in the camps of Cox’s Bazar from hampering the bilateral repatriation process through threats, violence or other illegal conduct also need to be strengthened, as such activities pose a risk to both Bangladesh and Myanmar.”

The reply from Bangladesh was predictable.

Exercising the country’s right to reply in the General Assembly, a Bangladeshi diplomat dismissed Myanmar’s complaint as “another blatant demonstration of falsehoods” and rejected allegations that Bangladesh is harboring any terrorists from Myanmar.

Recently, the Myanmar military increased security patrols along the border with Bangladesh.

Military spokesman Major General Zaw Min Tun said, “There have been increased activities by the AA and ARSA along the border in Buthidaung and Maungdaw townships [in Rakhine State]. While we have stepped up security measures, [Bangladesh] has openly raised objections. And it has also filed a complaint with the UN. So we have suspicions that it has a hidden agenda.”

Tensions between Myanmar and Bangladesh have risen steadily since two Myanmar soldiers were reportedly taken from Bangladesh to The Hague, the seat of the International Criminal Court in the Netherlands, after allegedly confessing while in the AA’s custody to committing atrocities against Rohingya civilians.

Insisting that Dhaka has a zero tolerance policy toward all forms of terrorism, Bangladeshi Home Minister Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal praised his country’s border guard force for maintaining security.

“We categorically assert that the terrorist groups such as ARSA and [the] Arakan Army do not get any indulgence from Bangladesh. There is no presence of ARSA and Arakan Army in Bangladesh,” he told BenarNews.

The home minister’s assurances notwithstanding, government and police sources in Bangladesh privately acknowledge they have arrested “several” insurgents in recent months.

The Myanmar government and military have declared both the AA and ARSA to be terrorist organizations. The AA is currently engaged in ongoing fighting with the Myanmar military (or Tatmadaw) in northern Rakhine.

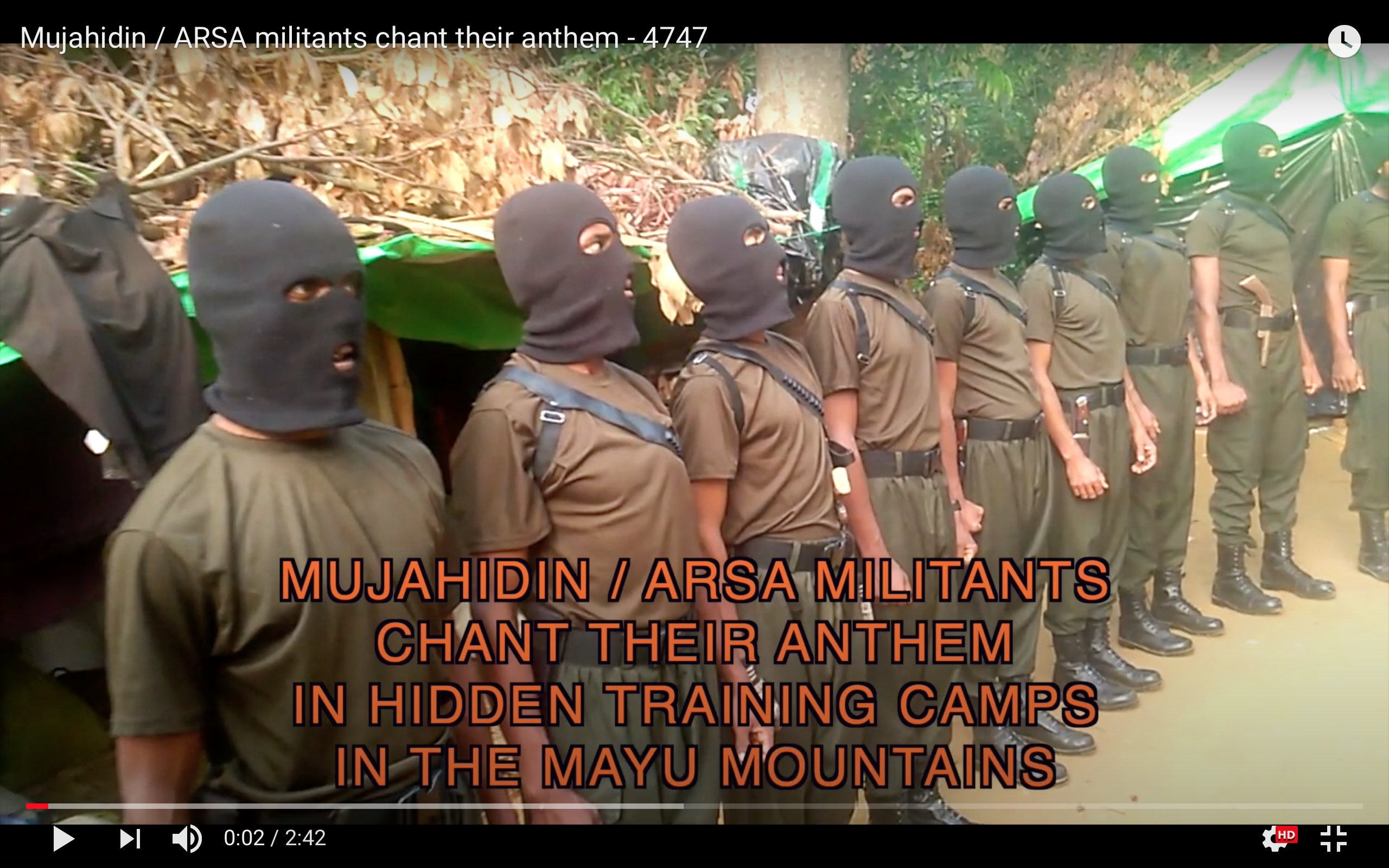

ARSA made international headlines when it launched a coordinated attack on 30 border guard police posts and an army base in Rakhine State in Myanmar in August 2017, killing 12 members of the security forces.

In fact, the group already had a history of instigating violence. In 2016, it stepped up its atrocities in northern Rakhine, committing mass killings of Hindu and other minority civilians. Indeed, the attacks marked a major escalation in the region’s long-simmering conflict and triggered the large-scale and violent army offensive.

ARSA’s attacks prompted the military to carry out clearance operations that forced an estimated 730,000 Rohingya into neighboring Bangladesh. Myanmar has since come under international pressure to hold military officers accountable for the mass exodus.

ARSA and AA members are hiding on Bangladeshi soil, but where exactly? In the refugee camps or in the hills?

In Cox’s Bazar, the district housing the Rohingya refugee camps, ARSA members move around freely and even conduct military training. The AA has also set up camps inside Bangladesh, including field hospitals to treat its wounded.

Both Western and regional intelligence agencies have full knowledge of the presence of the camps and the ongoing military training along the border. Myanmar officials who monitor the situation say small ARSA units have been seen training in the hills, but they always manage to melt into the jungle before the Bangladeshi border forces arrive.

In February last year, German news agency DW reported on growing concerns among local Bangladeshi officials that the Rohingya in the camps are vulnerable to a number of emerging negative external influences.

“Since they [the Rohingya refugees] came, the presence of arms and drug [traders] has increased,” Tofael Ahmed, chief of community police in Cox’s Bazar, told DW. “Many accuse some groups of instigating unrest in the camps. That is how they try to hinder the repatriation process.”

ARSA’s leader is Ata Ullah, a Rohingya who was born in Pakistan to refugee parents before moving to Saudi Arabia. He was reportedly educated in a madrassa, an Islamic school.

Downplaying the threat posed by the group, some Bangladeshi security analysts maintain that ARSA is a small, ragtag, poorly armed militant group with a voluble Twitter account, and insist there is no evidence that Bangladeshi forces or nationals are actively arming or training them.

It is true that ARSA’s statements and Twitter messages are well written—a reflection of the fact that there are several foreign-based groups involved in assisting ARSA and the wider Rohingya movement. Moreover, ARSA’s flags depict an outline map of Rakhine, suggesting that its agenda is to assert control over the Buddhist-majority state. This only heightens the fear and distrust toward ARSA that is felt in Myanmar.

Several years ago, regional and transnational jihadist networks began showing an interest in exploiting the plight of the Rohingya. Reports indicate that the international Islamic extremist group al-Qaeda included Myanmar on a 2014 list of its key targets.

In December 2016, al-Qaeda’s Bengali-language media output included a video call to arms to avenge the persecution of Muslims in Rakhine. Akayed Ullah, the Bangladeshi immigrant who detonated a pipe bomb in a New York subway corridor on Dec. 11, 2017, had visited the Rohingya camps three months earlier.

Observers continue to debate whether ARSA itself is a jihadi organization. But several Islamist groups in the region have adopted the Rohingya as a cause celebre, including Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), Islamic State, and al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent.

Regardless, analysts have long warned that the longer the Rohingya remain in the camps, the easier it will be for ARSA to bend them toward radical Islamism, and the more likely it will be that radical Islamist militant groups will commit violence on their behalf.

Myanmar’s criticism of Bangladesh is valid; Bangladesh’s denial that the AA and ARSA have a presence on its soil is baloney.

The only way to solve the issue is for the two countries to open up a regular dialogue, instead of trading accusations.

You may also like these stories:

Sacrifices of September 1988 Not Forgotten as Myanmar’s Long March to Democracy Continues

As Myanmar Charter Change Fails, a Good Time to Remember U Win Tin