YANGON—Muslims in Myanmar have found themselves the target of communal conflict—occasionally deadly—as anti-Muslim sentiment has increased along with a rise in Buddhist ultra-nationalism over the past several years.

The religious minority of 2.6 million people—about 5 percent of the country’s population of 51 million (according to 2014 census data)—have also been scapegoated by nationalists looking to incite bloody instability in the country. Using sharp anti-Muslim rhetoric, they claim that the foundations of Buddhism are under assault and that Buddhists must be vigilant against the influence of “fundamentalist” religions like Islam.

Politically, Buddhist radicals have stoked anti-Muslim sentiment in their attacks on the National League for Democracy (NLD), which they portrayed as a “pro-Muslim party” ahead of the 2015 general election. Apparently wary of being smeared as a party that the country’s Buddhist majority should not vote for, the NLD avoided fielding a single Muslim candidate in that election. Yet, many Muslims in Myanmar voted for the NLD in the hope that it would bring about democracy with equal rights for all people.

To contain anti-Muslim sentiment, when it came to power in 2016, the NLD-led government outlawed the Buddhist ultranationalist group MaBaTha and prosecuted the perpetrators of religious violence and incitement. However, many Muslims’ expectations, such as the establishment of freedom of religion or the removal of obstacles and delays to obtaining citizenship, have not been met. Some Rohingya and Myanmar Muslim applications to run as candidates in this year’s election were rejected by the election commission on grounds that their parents are not Myanmar citizens.

Myanmar’s election laws require that a candidate’s parents be citizens of the country.

A total of 38 million people are eligible to vote in this year’s general election scheduled for Nov. 8, including Muslims who are Myanmar citizens.

With less than a month to go until the polls, The Irrawaddy asked the Muslim community’s leaders and members about the community’s willingness to vote, their hopes for the election, what changes they want to see after the general election, and whether many Muslims plan to abstain from voting due to disappointment that their expectations in previous election haven’t been met.

‘Changing the system is not yet complete.’

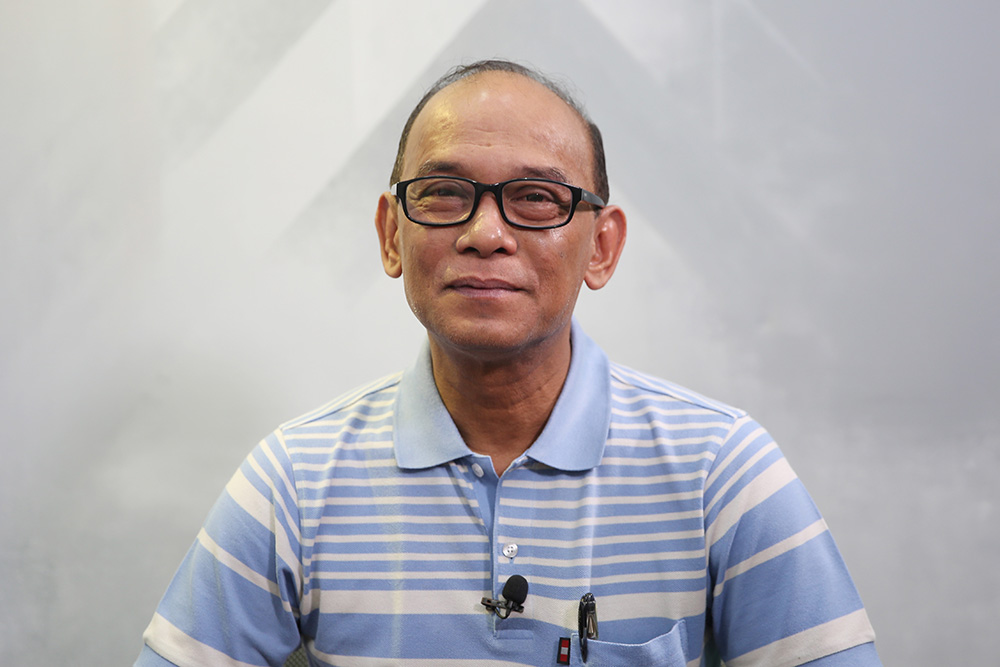

Al-Haj U Aye Lwin, the chief convener for the Islamic Center of Myanmar and a founding member of the interfaith group Religions for Peace-Myanmar, is deeply involved in peace building and conflict transformation in the country. He was a member of the now defunct government advisory commission on Rakhine State chaired by the late Kofi Annan. On the upcoming general election, he said:

“In this very important election for Myanmar, we, Myanmar Muslims, will participate responsibly and faithfully as we did before. I would like to say that we will support a force that values human rights, democracy and not bringing back the dictatorship.

“We had high expectations that the force [the NLD] would pull Myanmar out of decades of [military] dictatorship. In fact, the old establishment has not totally disappeared. It remains in power under the Constitution [they themselves created in 2008]. Not taking that fact seriously, we hoped change would happen immediately [after the 2015 election]. Yet, in reality, things didn’t turn out as expected over the past five years and thus dissatisfaction has grown along with a feeling that voting won’t change anything. But they [Myanmar Muslims] understand. The process of changing the system is not yet complete. As radical change is needed, religious minorities will vote in force.”

In terms of the government’s handling of racial discrimination and religious conflict, U Aye Lwin said the NLD government has taken quick and decisive action against those who insult religions—a significant change from the previous government led by the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), which was accused of doing nothing to curb incitement and hatred against Muslims, and religious riots. But due to the smear campaign against the NLD as “pro-Muslim”, U Aye Lwin said, the party has taken a cautious approach, even when it comes to ensuring equal rights for Muslims. He said the party is opposed to discrimination, but it does not want to be seen as favoring Muslims, either.

“Even if the NLD members [simply] attend an Islamic ceremony, the propaganda [by nationalists] spreads, tainting the party as a Muslim party, so they have to think hard before every single move.”

‘We want equal rights. Nothing more or less.’

The Muslim community leader said the community’s members continue to face a loss of basic citizens’ rights, including freedom of religion or belief. Many of its members face obstacles and delays in citizenship applications, and in being able to stand for election, as several Muslim candidacy applications were rejected by the election commission due to the citizenship status of the applicants’ parents.

In 2015, more than 100 would-be candidates had their applications rejected, most of them Muslims. Twenty-eight Muslims contested the election, but none were elected. In the Nov. 8 poll, around 20 Muslim candidates are running in the election.

U Aye Lwin welcomed the inclusion of Muslim candidates in the main political parties’ candidate lists, including the NLD and the Democratic Party for a New Society (DPNS). The NLD fielded two Muslim candidates, one each in Yangon and Mandalay, whose candidacy applications the party rejected in 2015.

“We don’t seek favors. We just want to gain the rights of ordinary citizens,” he answered when asked about what changes he wants to see for the Muslim community after the 2020 election.

Well-known Muslim writer Dr. Myint Thein, who is also known as Nyein Chan Lulin, shared the same wish—that his community would achieve equal rights as citizens after the election.

“We can’t deny that rights violations occur in Myanmar. There is discrimination against individuals because of their religion or beliefs. As a Myanmar citizen, I want equal rights as a citizen, nothing more or less.”

The writer said Muslims suffered more during the previous U Thein Sein government’s time, as authorities turned a blind eye to the perpetrators and instigators of anti-Muslim riots, allowed Buddhist nationalists to operate with relative freedom, and failed to intervene to protect the community during religious riots. The places of worship and homes that were torched in the riots have yet to be fully restored, he added.

The situation has improved to some extent under the NLD due to the government’s quick responses to incitement and interfaith friends’ opposition to violence against Muslims, he said.

He gave the example of the case in Yangon’s South Dagon Township, in which a nationalists mob forced the closure of three temporary worship sites for Muslims in May 2019. The Yangon regional government had given permission for the buildings to be used during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan.

Public defiance of nationalists prevented further violence, the writer said. The prayer sites were reopened within a few days and those who led the mob were jailed.

‘We want equal protection under the law.’

“We know the NLD tried to provide [more] protection [to the community than before], but it used temporary solutions to deal with the problems. But what we want is for the system to change, and protection by law.” For example, offering temporary prayer sites is not a solution to a lack of places to worship, Dr. Myint Thein added.

“As there have been no systematic changes, there is dissatisfaction. But we need to see clearly that they [the government] weren’t unable to achieve that—whether it was because they didn’t want to do it, or because the conditions weren’t right from them to do it.”

‘‘No vote’ campaign could lead more disadvantages.’

“Many people, responding emotionally, said they won’t vote in the coming election, out of disappointment. But given the current political climate in Myanmar, there shouldn’t be a ‘no vote’ [campaign]. That would be giving up a right we can exercise. We need to consider whether a ‘no vote’ campaign would actually be effective or just lead to more disadvantages,” Dr. Myint Thein said.

Ma Rosey, a member of the Myanmar Muslim Education Committee based in Bago Region, who has also worked as an election observer since 2015, said she heard a lot of people earlier saying they would abstain from voting in the election because of their frustrations, but now they have changed their minds, as they understand the importance of their vote and are keen to exercise their right.

‘I want to see representatives who will speak out for the rights of minorities.’

“As a Myanmar Muslim, I want to see more changes [after the 2020 election], especially having representatives who will speak out for the rights of minorities in Parliament. And I want a safe environment for all of us. We could say the protection of security for the Muslim community has improved to some extent under the incumbent government. We have seen less violence [towards Muslims]. And previously, an incident of violence often set off a chain reaction of further violence and there were large numbers of resultant fatalities. Now, such cases are prevented. Still, we continue to face violence in ethnic areas, as well as towards the Muslim community. Conflicts have erupted in Rakhine State. Our rights are still being repressed. It is sad to see incidents of violence toward minorities and loss of life.”

‘The election is a milestone on the road to democratization.’

Ko Mya Aye, a leader of the Federal Democratic Force and one of the leaders of the ’88 Generation Students Group, said:

“Despite so many people calling for a ‘no vote’ in the upcoming election, it will turn out differently on the ground on election day. Thanks to their political awareness, many people will vote. Voter turnout will only depend on the COVID-19 situation. If it is brought under control, the voter turnout will be high.”

You may also like these stories:

Sacrifices of September 1988 Not Forgotten as Myanmar’s Long March to Democracy Continues

As Myanmar Charter Change Fails, a Good Time to Remember U Win Tin