In the early 1960s, when Maung Maung was attending the 7th grade, his grandmother gave him a His Master’s Voice (HMV) gramophone, locally called as dog brand gramophone, a present that obsessed him for the rest of his life.

“This was one of the main factors that inspired me to collect gramophone records,” said Maung Maung, who is commonly known as researcher Maung Maung.

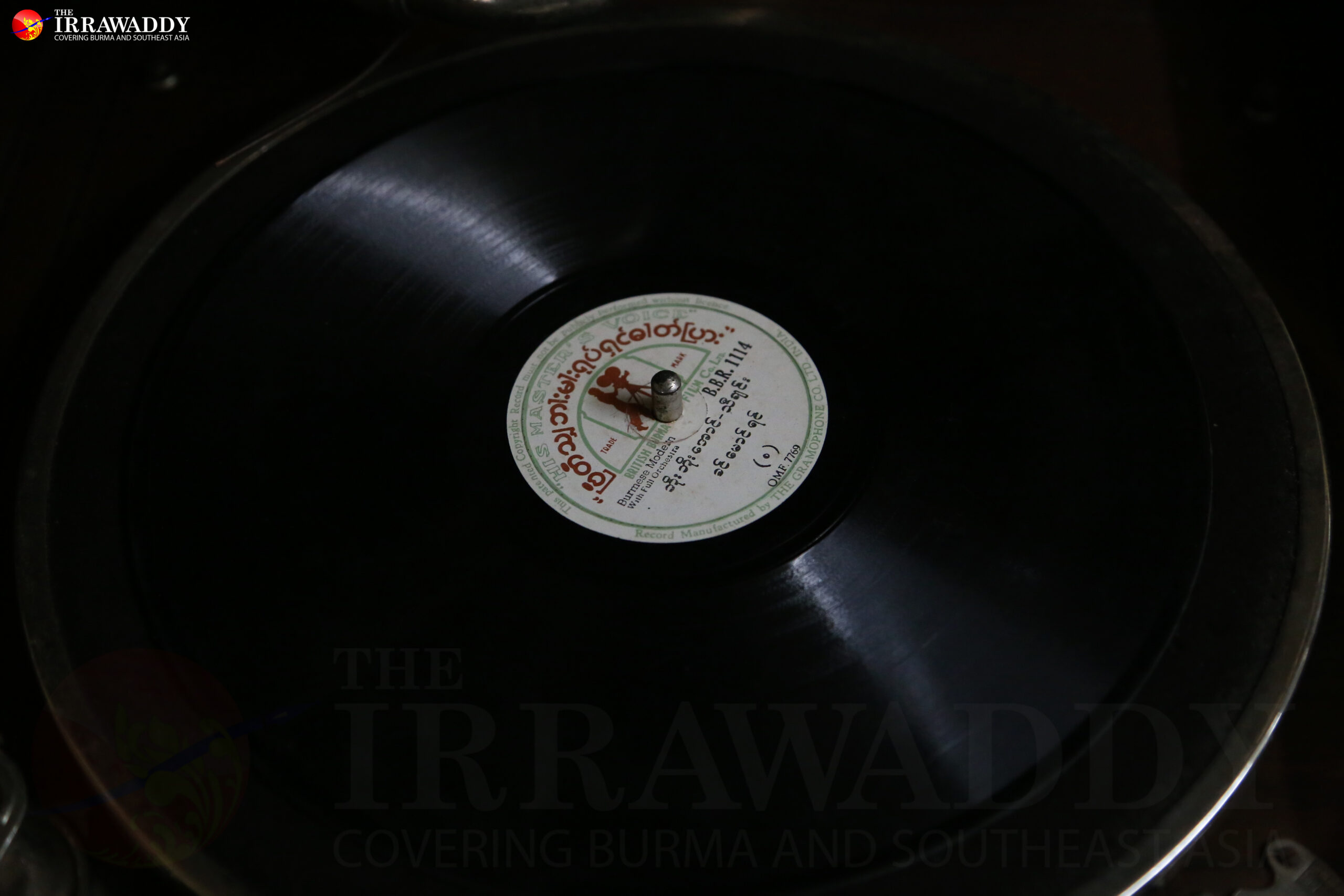

When it comes to the history of the gramophone in Myanmar, no one knows as much as Maung Maung who has collected almost a century’s worth of gramophone records—from the records of a play by Saya Pu—a court artist in the reign of Myanmar’s last monarch King Thibaw in late 19th Century—to the last gramophone record produced in Myanmar in 1976 by classical musician Kyaukpadaung Kyaw Lwin in 1976.

He started collecting gramophone records while he was a student after his grandmother gave him a gramophone and kept on collecting through various stages of his life as a university student, a police officer, and then a lawyer.

Gramophone records have recorded Myanmar’s classical music, traditional culture and historical events that were previously passed down from generation to generation by word of mouth as well as from books and literature, he said.

“Around 1972 I was attending university [in Yangon] and gramophones started to lose popularity,” he recalled, “Because of the invention of cassette players and the decline in quality of gramophone records.”

He related the quality decline to the socialist system being practiced by Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP) at the time.

As cassette players became popular, people were selling their old gramophones to dealers. “At that time, people started to exchange their gramophones for cassette players. Later, gramophones were [discarded and] stacked in piles like bricks.”

“Nobody would stop you if you take them because people thought they were garbage and you’ve just cleared it. If I had been the director-general of [State Broadcaster] Myanma Radio and Television [MRTV], I would have taken them by car,” he said about the demise of gramophones.

He scavenged through piles of gramophones and records in Yangon and took his favorites back to his native Daik-U Township in Bago Region.

“My father also helped me collect newspaper adverts for gramophone records,” he said.

After he graduated, he worked as a school teacher back in Daik-U and taught his students Myanmar literature and nationalism which was taken from Anyeint and marionette songs, and plays in gramophone records, which he had collected.

Then he joined the police force and served as a police chief in a number of townships in Bago Region.

“While I was serving as a police chief, I told second-hand goods dealers like this. I don’t care anything else but gramophones and records. I would buy any, and any consequence is yours if you don’t sell me,” he explained how he collected gramophone records.

When he heard somebody had some rare gramophone records, he went there along with his gramophone. He bought gramophone records if owners sold, but when owners didn’t, requested owners to let him play it on his gramophone.

He continued collecting gramophone records while he was working as a lawyer after retiring from the police force. He continued to get gramophones and records from his clients and friends.

Former information minister U Kyi Aung, who is also a gramophone fanatic, once solicited him to donate his gramophone records to his ministry, but he refused.

However, with the approval of the minister, he got an opportunity to group the gramophone records of MRTV according to their genres.

“MRTV has plenty of gramophone records, but not as many as my archive in terms of records with real historical values, for example, only I have the original record of the song Doh Bamar which was the origin of today’s Myanmar national anthem and sung by Thakhins in colonial period.”

“However, that was very beneficial to my research on gramophones. I am grateful to authorities for this,” he said.

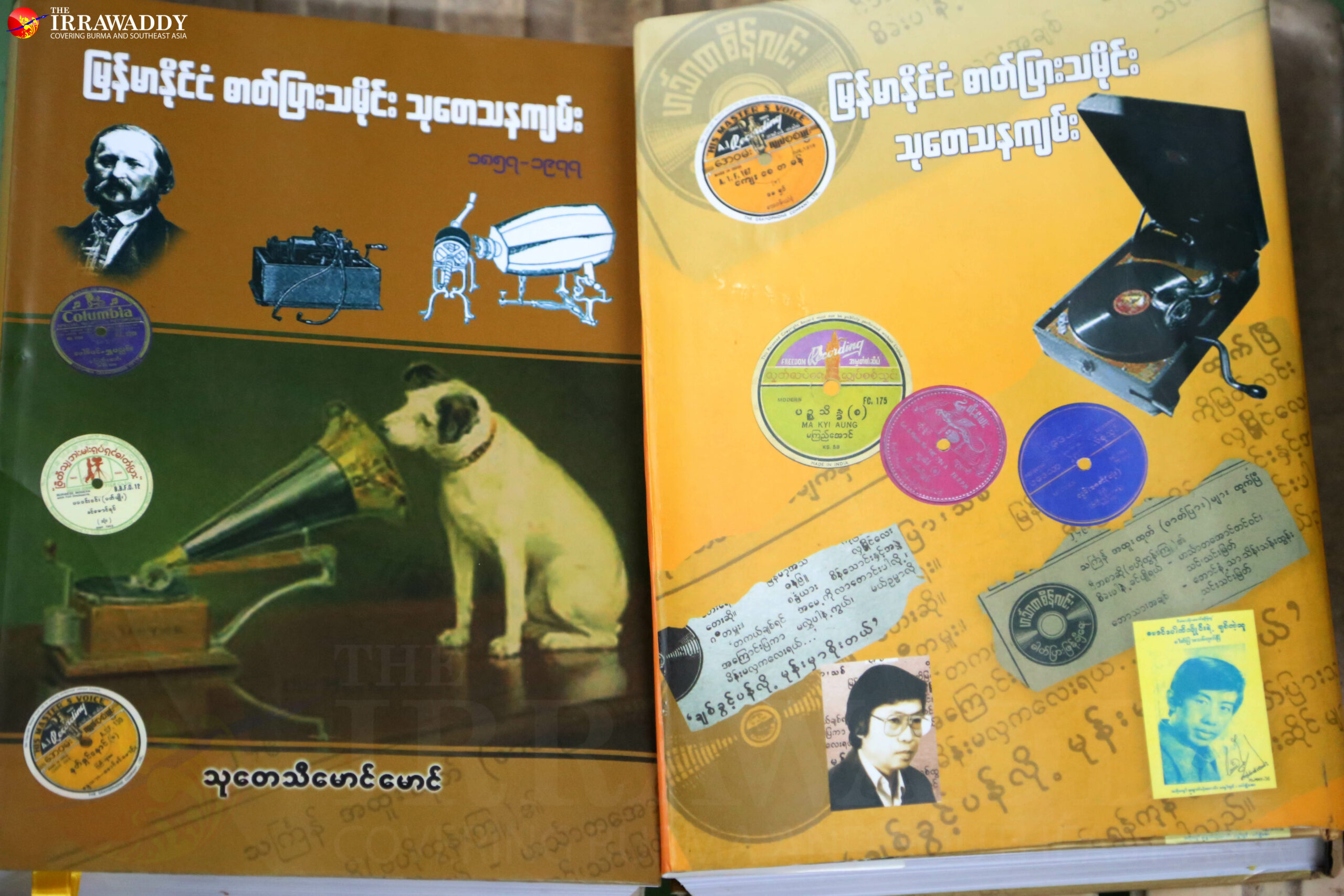

Based on his collection of records, newspaper clippings and adverts and references, he published a 1000-page research book on the country’s gramophone disc history, for which he won the national literature award in 2015.

Regarding the book, historian Dr Toe Hla said: “This is a book which has never existed before, and which every artist should keep.”

“From this book, scholars and researchers can find the history of artists and songs of eras, and socio-economy and faith reflected by songs,” he remarked.

“I collected them because I’m crazy about it. I’ll figure out the arts, history, literature, tradition and culture reflected in those records. I will share the quality of old classical Myanmar songs and standards of Myanmar literature to younger generations and international gramophone disc researchers,” he said.

About the future of over 100,000 records which he collected for nearly six decades, he said: “Frankly speaking, I don’t expect to receive help from the [information] ministry.”

“If I say something, they [information ministry officials] would reply they would submit a letter to the minister or come back again at this or that time. I don’t care. In fact, they should come to us. If they don’t, I will do it on my own. But if there are people who know the value and can afford to keep my records in a museum or alike, I will transfer them,” he said.

“I’ll keep on collecting those records. That’s my life,” he said.