In this first installment of a two-part interview, human rights campaigner Igor Blazevic asks Jason Tower, country director for the Burma Program of the United States Institute of Peace, about Beijing’s recent moves in relation to the Naypyitaw regime and the ethnic armies on China’s border with Myanmar.

Blazevic: Jason, in your recent article “The Limits of Beijing’s Support for Myanmar’s Military,” you argue that the Chinese government is changing its approach to Myanmar. What has changed and why?

Tower: China is in a rapid way bringing an end to its COVID-zero policy. Over the past three years, Chinese business actors could not really travel overseas. Even more importantly, the number one policy focus of Chinese government officials was on containing COVID-19. Rapid change happened in December and January and it immediately shifted to focus on resetting the economy.

Down on the China-Myanmar border, this has major implications for Yunnan Province, which has a development strategy focused on connectivity through Myanmar. Business stakeholders and government officials are now focused on implementing cross-border development schemes, trying to address major electricity shortages and reset major infrastructure and connectivity projects in Burma. My expectation is that we are going to see more and more businesses from Yunnan and from across China pouring into Myanmar, looking for business opportunities. We will see projects starting to spin. We will see the Yunnan government trying to push ahead with businesses as normal.

There are other factors as well. First, you have growing international interest for some form of intervention in Myanmar to bring an end to the military’s disastrous war against the Myanmar people. Beijing is highly sensitive to the internationalization of conflict in Myanmar. Since December of 2022 when the Myanmar issue was brought once again to the UN Security Council, Beijing moved to become much more active on the Myanmar issue, deploying a new Asian Affairs Special Envoy to support negotiations between the military and northern EAOs [ethnic armed organizations]. With ASEAN [the Association of Southeast Asian Nations] continuing to be divided, and with growing calls for ASEAN to take much bolder steps, Beijing is concerned that other international actors might build increased influence over the trajectory of the conflict—something which Beijing ultimately wishes to prevent.

Blazevic: Is China becoming nervous about the length of post-coup instability in Myanmar, or can it remain patient and wait to see how the internal conflict evolves?

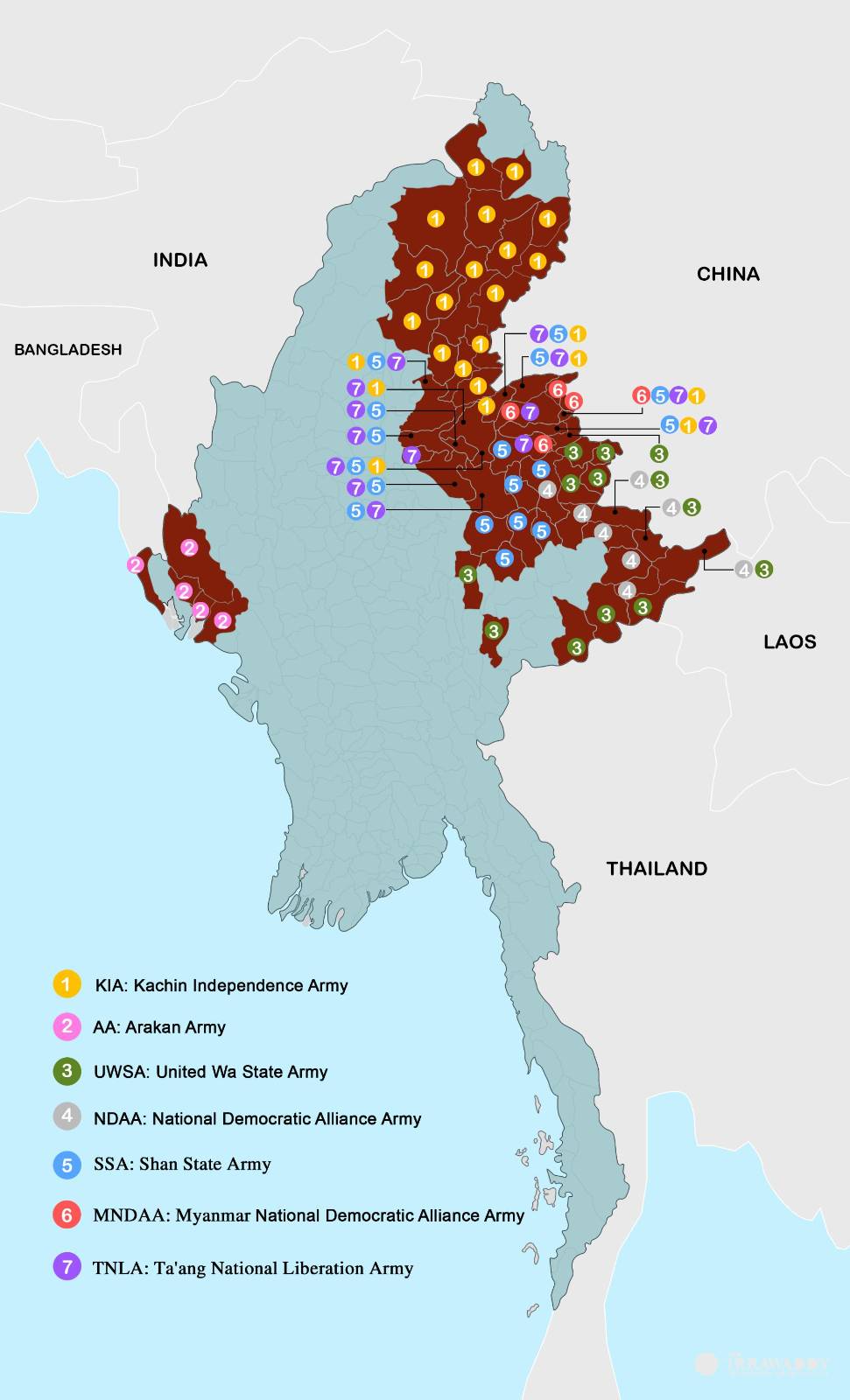

Tower: China is increasingly concerned. The military’s announcement of the extension of the state of emergency in February was a public admission that it has lost control, and this has generated concerns on the part of all of Myanmar’s neighbors. The open admission that over 40 percent of townships are out of military control is a source of anxiety for China, which has vast geo-strategic economic interests in Myanmar. China has also observed the military’s poor performance on the battlefield right on its doorstep. Key armed groups, including the TNLA [Ta’ang National Liberation Army] and MNDAA [Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army] have defeated junta forces deployed to the frontlines with surprising ease, and continue to raise new battalions and expand their influence. There is a concern in Beijing that the junta lacks the capacity needed to hold elections and reinstitute authoritarian control under a pro-military political party.

Fighting is also intense right near China’s strategic energy route through Myanmar, which provided Yunnan with more than 10 percent of its GDP. China plans for a railroad to be constructed right along this corridor, which in Shan and Magwe is now a magnet for People’s Defense Forces and powerful ethnic armed organizations. For China this is a major worry, as its energy security is now threatened by the violence, and because connectivity projects such as the railroad will likely be placed on hold over the short to medium term as violent conflict becomes protracted.

Blazevic: Does China have any clarity as to the most desirable outcome of the current crisis for its own interests? Is China ready and able to leverage development in that direction?

Tower: I’d say China is agnostic as to which party controls what piece of territory. It is much more focused on securing its geostrategic interests, advancing its economic projects and checking Western influence in its frontier areas. I don’t think China really has a clear understanding which outcome it wants. In my recent article I argue that China’s approach is to strengthen its support for which it sees as the most powerful players in Burma—a coalition of northern EAOs under the leadership of the United Wa State Army on one side, and the military and its State Administrative Council on the other. China is looking at how it uses its leverage over these parties to influence the overall trajectory of the conflict in a direction favorable to China’s interests and which can check external influence in Burma. If Beijing has its way, this will be a boon for the northern EAOs, which will consolidate their positions and extend Chinese influence deep into Kachin and Shan states; this will also help the military focus its overstretched resources on battling PDFs and EAOs aligned with the NUG.

There is also another factor. The PRC is increasingly supplementing its economic Belt and Road Initiative with the new Global Security Initiatives [GSI] that the Chinese government unveiled last year. China recently issued a white paper on the GSI, sending a very strong signal that it intends to play a much more robust role in security affairs globally. For Southeast Asia, this White Paper emphasizes that China will focus on the Lancang-Mekong Region, implying that China will leverage its Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Forum to address the Myanmar issue—something which it quietly started in 2022. In early March, China sent a strong signal of its intention to assist the Myanmar military bolster its international legitimacy when it took the unprecedented step of brokering the establishment of diplomatic relations between the military junta and Guinea Bissau in Beijing.

Blazevic: Can China deal with a Syria type of outcome in Myanmar, with the junta controlling just part of the territory and several militias controlling other parts? Or would China like to see strong central power in Naypyitaw as a guarantor of stability?

Tower: There is a significant level of distrust between the Chinese government and the Myanmar military. This is fairly deeply rooted. It goes back to the history of formation of the Myanmar armed forces, China’s own civil war spilling over into Burma, and its desire to support a communist revolution in the country, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s. While China ended support for the Burmese Communist Party in the late 1980s, and set about building a comprehensive strategic partnership with the central Burma military authorities in the 1990s, these efforts were seriously aggravated by more recent efforts of the military to consolidate its control and challenge rising Chinese influence in the country. In 2009 for example, [junta leader] Min Aung Hlaing himself led an operation to defeat one of the key ethnic armed organizations right on the China border—the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, or Kokang. This resulted in tens of thousands of refugees fleeing violence across the border, and a major shift in Chinese influence over a key trading hub. Even more importantly for China’s interests, the [government led by the] pro-military party, the USDP [Union Solidarity and Development Party] suspended a multi-billion-dollar dam project in Kachin State, the Myitsone Dam, which is something that senior government officials in China remain bitter about, particularly given the recent energy shortages in southwestern China.

Given the lack of trust with the military, China’s preference is to maintain powerful ethnic armed organizations as allies in the northern part of the country because it gives it leverage over the military. China continues to arm, train and assist these groups because it helps create a buffer in the border area, consolidates Chinese influence, and equally importantly, creates strategic needs on the part of the military vis-à-vis China. Those northern EAOs will also do quite a lot in extending Chinese influence further south, particularly into the important space down in the Golden Triangle at the upper region of the Mekong River. China looks at the Wa and MNDAA as an opportunity to expand its influence into neighboring countries and over the strategic waterways.

By balancing its relationship with the northern EAOs and the military, China has a much better ability to meet some of its interests than would be the case with a very strong central Burman state. A strong central government might be in a better position to leverage relationships with neighbors or with other external parties to hedge against Chinese influence and ultimately get a better deal in bargaining with China.

Blazevic: If northern EROs [ethnic revolutionary organizations] that are seen as under China’s influence are expanding their control, is that making Thailand nervous? Could that trigger a change in the Thai policy towards Myanmar, because they will be worried about Chinese influence expanding closer to their borders?

Tower: I don’t think Thailand necessarily minds more investments coming in or it minds the growing economic partnerships. What Thailand is clearly nervous about is the growing presence of “grey business” or “illicit business,” which will likely expand dramatically given the involvement of some of the northern EAOs in narcotics production. Then, if you look at what might come along, in terms of China having more influence on the Mekong River, potentially larger and larger Chinese ships coming down the Mekong River, China having more and more control over the Golden Triangle region, these are things that Thailand has traditionally been very sensitive to. They don’t really want to see growing Chinese security influence in the region.

Thailand is showing signs of responding to this. In particular is a very significant crackdown on as the “gray business influence” in Thailand. Over the past eight months, the Thai police have arrested a series of high profile [China]-affiliated triad leaders operating in Bangkok, including the notorious She Zhejiang, who was operating a massive criminal city right on the Thai-Myanmar border in partnership with the Myanmar army’s border guard force.

Jason Tower is the Country Director for the Burma Program of the United States Institute of Peace. Jason has over 20 years of experience working on conflict and security issues in China and Southeast Asia. Since 2019, his research has focused on a range of issues at the nexus of crime and conflict in Southeast Asia and on China’s influence on conflict in Myanmar.

Igor Blazevic is a senior adviser at the Prague Civil Society Centre. Between 2011 and 2016 he worked in Myanmar as the head lecturer of the Educational Initiatives Program.