TAUNGGYI, Shan State — Sitting at his home in Taunggyi, 100-year-old U Khan is still proud of what he did for Gen. Aung San, the father of Burma’s independence, in February 1947.

Nearly 70 years ago, U Khan drove Bogyoke (General) Aung San along a narrow, steep and snaking road that stretched 100 km from Taunggyi to Panglong, where the national hero and ethnic leaders from Shan, Kachin and Chin states signed the historic Panglong Agreement as part of efforts to speed up Burma’s return to independence from British colonial rule.

Unsurprisingly, none of the leaders who signed that agreement is alive today. Aung San was the first of them to die, assassinated as he was on July 19, 1947, just six months before the country gained its independence.

Born in 1915, the same year as Aung San, U Khan remains in good enough health that he can still be seen driving occasionally in his hometown of Taunggyi, where he was born to a migrant Muslim father and a Shan mother. U Khan still considers himself a devout Muslim.

He remembers the past clearly, including the small part that he played in history, and is happy to show guests old photos hung on the walls of his house.

“I drove him [Aung San] to Panglong,” he told me, pointing to a photo of Aung San receiving a bouquet from a young local woman in Taunggyi, U Khan himself pictured sitting behind the steering wheel of a Jeep just before setting off for Panglong.

When they arrived at Panglong but before signing the agreement on Feb. 12, U Khan recalled Aung San telling the gathered ethnic leaders, “You can separate your states from Burma after 10 years if you are not satisfied with [this agreement].”

U Khan said: “Ethnic leaders, including the Saopha of Yawngwhe [who would become Burma’s first president after independence in 1948], responded to Bogyoke Aung San by saying, ‘Let’s not talk of secession at the moment; we are just about to sign for a union.’”

Feb. 12 has since been recognized annually as Union Day and the historic Panglong Agreement remains a rallying point for Burma’s ethnic minorities, with its guarantee of full autonomy for ethnic regions never realized and still sought to this day.

Common Interests

U Khan and Aung San had become acquainted thanks to their common interests in politics and their country’s struggle for independence.

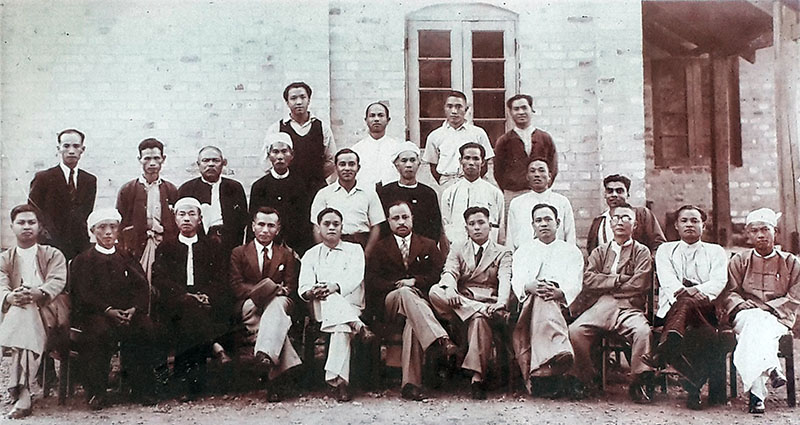

“Bogyoke Aung San was involved in the nationwide independence struggle, while we were involved in political activities here in our Shan State,” U Khan said. “I worked with U Tin E for the Shan State People’s Freedom League.”

The late Tin E, who was one year U Khan’s junior, was one of a handful of prominent Shan leaders who managed to convince many Shan to support Aung San’s Panglong plan to expedite independence from Britain, which was seeking a show of unity before agreeing to relinquish the whole of Burma.

In 1952, four years after the country had ridded itself of the yoke of colonialism, U Khan was elected as the first mayor of Taunggyi, the capital of southern Shan State. Four years later, he was re-elected to a second term and was also appointed chairman of the Taunggyi Municipal Committee.

As mayor in the 1950s, U Khan received domestic and foreign dignitaries during his time in office. Other photos on the walls of his home capture the centenarian with Burma’s President U Ba Oo and visiting Chinese President Liu Shaoqi, both of whom paid visits to Taunggyi. The premiers Kyaw Nyein and Ba Swe were also among his acquaintances at the time. While serving as mayor, he was also a successful businessman, running movie theaters and a construction company that operated in Taunggyi and other towns in southern Shan State.

However, doomsday came for him on March 2, 1962, when the late dictator Gen. Ne Win staged a coup, ousting from power the civilian government led by Prime Minister U Nu. Indeed, that fateful Friday was a dark turning point not just for U Khan, but also for the entire country.

In the wee hours of March 2, Ne Win’s troops began surrounding the homes of cabinet members as well as ethnic leaders, most of whom were Shan princes, known as saophas, in Rangoon and across Shan State. The soldiers arrested the entire cabinet, including the then incumbent President Mahn Win Maung (an ethnic Karen), U Nu and the rest of the government ministers. In Shan State, almost all of the 25 Shan saophas who were members of the regional Nationalities Parliament and another 25 members of the People’s Parliament were arrested along with other politicians.

Burma’s former first president and the incumbent chairman of the chamber of nationalities, the saopha of Yaunghwe Sao Shwe Thaike, was among the purged Shan princes, having also been apprehended at his residence in Rangoon. During the arrest, one of his teenage sons was killed. Ne Win’s regime said he died as guards at the saopha’s residence exchanged fire with the soldiers attempting to arrest Sao Shwe Thaike. It was reportedly the only casualty of an otherwise bloodless coup.

Ne Win’s takeover destroyed the union spirit that had been forged by Aung San and the ethnic leaders at Panglong, with the Burman-dominated military junta entrenching distrust between the country’s ethnic majority and its many ethnic minorities. Without question, it dealt a devastating blow to hopes of ending Burma’s civil war, which by that time had entered into its second decade.

‘Come With Us for a While’

U Khan was also among those arrested.

“I was sent to Insein’s annex jail,” U Khan told me, referring to a compound within Insein Prison, a penitentiary in Rangoon that has housed thousands of political prisoners since the 1962 coup.

Sao Shwe Thaike and other politicians were also kept at Insein, where U Khan told me he still can’t forget one morning in November 1962.

“Around 7 am, Sao Shwe Thaike shouted to us, ‘How are you guys?’, while he was taking a walk to work out in the prison compound,” U Khan recalled. “At around 11:00 am, he died. We had no idea why.”

“He was poisoned,” one of my friends, seated next to us, interrupted. U Khan responded: “I know, I know. Not good to talk about it.” The former president was believed to have been killed while in detention.

After having spent six years in the country’s biggest prison, U Khan was finally released without facing any charges. Though he was no longer behind bars, he wasn’t truly free.

Authorities did not allow U Khan to return to Taunggyi, instead forcing him to remain in Rangoon where they could better keep an eye on him and his activities. He was placed under this “city arrest” for four more years.

“They [authorities] just told me to come with them for a while,” U Khan recalled of the moment in 1962 when he was rousted from his home. “That ‘for a while’ meant 10 years in detention.”

Some businesses belonging to U Khan were confiscated by Ne Win’s Revolutionary Council, including two cinemas, as the government nationalized commerce across the country in the name of the “Burmese Way to Socialism.”

“At one of those locations, you can see Innwa Bank today,” he said, perhaps adding insult to injury for the man, given that Innwa Bank was founded by the Myanmar Economic Corporation, a conglomerate owned by the military.

U Khan has never received any form of compensation for the businesses he lost. After his release, he went back into the construction business in Taunggyi, but chose to remain outside the civic arena.

“I didn’t return to politics,” he said.

And though his past woes are attributable to a dictatorship that has ostensibly ceded power, Ne Win and his military successors still cast a shadow.

“I shouldn’t have talked a lot to you,” he told me as our conversation neared its end. “If I talk a lot, I am afraid that I might be ‘invited’ to prison again.”

Then, when asked whether he thought the current reformist government was as bad as the previous regime, he answered immediately: “I didn’t say it’s bad. It’s good.”

He continued: “Don’t write anything bad of the government. I don’t say bad things about the government. The government is really good.”

I asked a general question about Taunggyi and he replied in a similar vein.

“Everything is good. Yes, it’s good. Don’t write anything against the government. Just say everything is good. This government is also very good.”

At this point U Khan’s son jumped into our conversation: “He no longer dares to say anything critical.”

One of the reasons, his son explained, is that U Khan was again detained for a few days when a nationwide pro-democracy uprising rocked the country in 1988, despite his having steered clear of politics for decades.

More than a half century after his arrest, I can feel that the 100-year-old still lives in fear.

Though he is no longer willing to engage in politics, it hasn’t dampened his interest in the subject, nor caused him to shy away from visible affiliations with the country’s opposition.

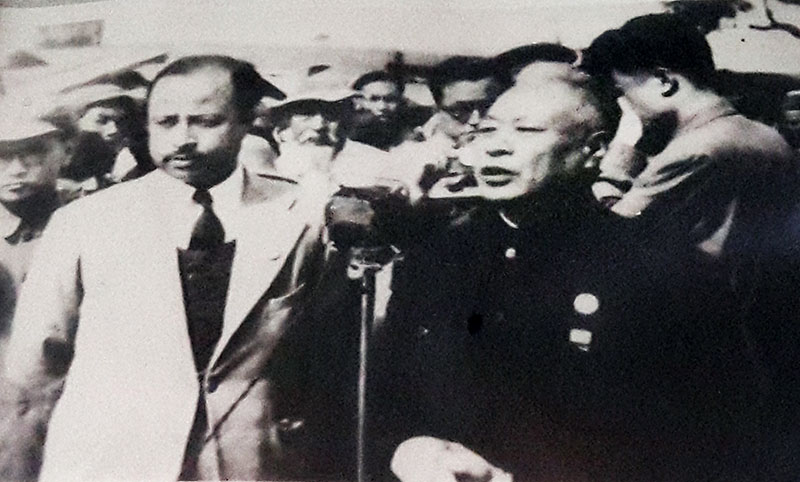

One photo hanging on the chimney in his living room shows U Khan with Tin Oo, a former commander in chief and founding member of the National League for Democracy (NLD), Burma’s largest opposition party led by Aung San Suu Kyi.

“He [Tin Oo] visited my house in recent months. Daw Suu [Aung San Suu Kyi] is very good and smart. I am not a politician but am interested in politics,” U Khan said. “I want to see Burma as a good country.”

Whatever the past, U Khan said life at his ripe old age is peaceful and filled with contentment. He still goes to the office most days after morning prayers, though he no longer handles the business responsibilities and simply enjoys meeting up with his friends to shoot the breeze.

“Sometimes I am still driving, but I don’t have a driver’s license anymore,” U Khan said. The licensing department, his son said, stopped issuing him a driver’s license after deeming him too old to get behind the wheel.

“But he is quite impatient if I drive,” said his son with a laugh, leading one to wonder what kind of harrowing road trip the apparent lead-foot may have embarked with Bogyoke so many years ago.