RANGOON — Hmyar Ni still remembers how his nearly 10-member editorial team crowded around a small attic in Burma’s biggest city to write articles and lay out his daily newspaper, Our Cause, 25 years ago

It was late August 1988, several days after the government brutally cracked down on pro-democracy protesters trying to topple then-dictator Gen Ne Win’s regime. Outside the newspaper bureau, the streets of downtown Rangoon had ground to a halt, as the country trembled with the people’s determination to oust a dictator who had oppressed them since 1962.

The days were chaotic but had a silver lining: a brief return of press freedom to a country that had been muzzled by a literary censorship system for the past 26 years. Newshounds like Hmyar Ni and his friends ventured out to report and publish independent newspapers, taking advantage of the government’s inability to restore Burma to normalcy.

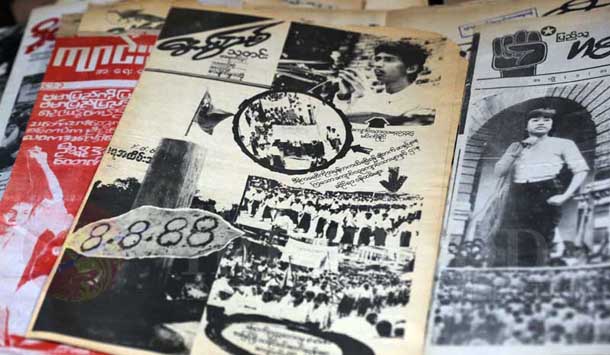

Starting around mid-August 1988, newspaper boys hawked morning and evening papers featuring photographs and accounts of ongoing demonstrations against the Burmese authoritarian government. Some editions were handwritten and then photocopied or mimeographed, while others were professionally printed.

“As far as I’m concerned, there may have been more than three dozen dailies and weeklies like us at that time in Rangoon” the 64-year old Hmyar Ni said.

It was the first return of privately owned daily news publications in modern Burmese history, long before the resurrection of today’s private dailies in April with permission from the quasi-civilian government. The Southeast Asian country had lost freedom of expression after the 1962 coup, when Ne Win shut down nearly two dozen private papers and established a draconian censorship board to ban anything that would disgrace his government.

The resurrection of independent publications in 1988 was short lived, however. The newspapers published only from mid-August to Sept.18, when a new military government came to power.

“We just grabbed the chance we had at the time,” said 77-year-old Maung Moe Thu, editor of the Warazein news weekly, which lasted four weeks. “We enjoyed freedom of expression during that short period because there was no longer censorship.”

His weekly was in broadsheet format, while other editors opted for tabloids. Like many newspapers at the time, his paper sought to oppose dictatorship by covering ongoing democracy movements across the country. Sales soared as the public heartily welcomed a chance to learn more about the demonstrations.

“Any move against the government became news,” Hmyar Ni from Our Cause daily said with a laugh. “Everyone became reporters overnight because they were always calling to give us information.”

Win Tin, a veteran journalist and co-founder of the country’s main opposition party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), said the 1988 newspapers became “voices of the 88 Uprising” by documenting the wishes of the public. He added that some entrepreneurial editors made lucrative businesses from the brief return of press freedom, referring to newspapers that published graphic photographs and unethical stories about the demonstrations.

“As a whole, you could hear people’s voices and find out how much they disliked the government in those papers,” he said. “It was the first time they could unleash their anger.”

Mandalay, the second-biggest city in Burma, also saw a boom of independent newspapers. Hsu Nget, a Mandalay-based writer, recalls that nearly 30 privately owned papers hit newsstands in the city. Among them was the Four-Eights daily—named after the 8/8/88 uprising, or the 88 Uprising—where he worked as an editor.

“People had a hunger for news,” he said. “They really wanted to know what was happening, and where. They had to rely on Burmese services from the BBC or VOA [Voice of America], but at that time not everyone could afford to buy a radio, so they turned to our newspapers.”

Among those who embraced the brief return of press freedom were journalists from the government’s six daily newspapers, which usually served as propaganda tools for the state. Several days after the country took to the streets on Aug. 8, journalists at these papers restored their first loyalty to the public.

“We publicly announced that we had left behind censorship and were now with the Burmese people,” said Ko Ko Gyi, who was then editing The Mirror daily, one of the state-run papers. “We told them to wait and see tomorrow’s paper.”

They kept their promise, with full coverage the next day of demonstrations across the country. When Burma’s democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi made her first public appearance at an open ground near Shwedagon Pagoda’s western stairway on Aug. 25, Ko Ko Gyi allocated a spot on his front page for the story.

The press freedom came to an abrupt end on Sept. 18. At 4 pm that day, a male announcer on the state-run Burma Broadcasting Service (BBS) proclaimed that “in order to bring a timely halt to deteriorating conditions all over the country. … in the interests of the people, the defense forces have assumed all power in the state, effective from today.” The broadcaster’s regular programs were then interrupted by strident martial music.

With news of the military coup, nearly all independent newspapers quickly shut down their operations for fear of retribution. Editors burned the draft layouts they had prepared for the next day’s papers and went into hiding. Photojournalists looked for secret places to stash away the negatives of photographs that had captured historic moments from the previous month.

Soldiers arrived at The Mirror’s bureau in downtown Rangoon at 2 am on Sep 19.

“They stormed into our office to confiscate dummies for the next day’s paper and seal the office,” Ko Ko Gyi said. “Then they kicked us out!”

Shortly after the generals in olive green uniforms came to power, military intelligence officers combed through the country to arrest anyone who had been involved in publishing the newspapers. But to people’s surprise, the journalists were only detained temporarily for interrogation.

“To the best of my knowledge, people weren’t seriously punished for publishing the newspapers,” Hmyar Ni said. “For my paper, only a few senior editors were taken away for questioning. They were released very soon.” He himself was spared from detention.

Ko Ko Gyi was not so fortunate. He was arrested three days after the coup and taken to an interrogation center, where he spent the next 20 days. Upon his release, he was forced to retire from his job. He was 54 years old, or six years shy of official retirement.

Now 77, the veteran journalist doesn’t seem remorseful about the decisions he made more than two decades ago.

“I’m proud of what I did,” he told The Irrawaddy.

“For me, it was the time when we suddenly saw a flash of light after 26 years of darkness.”