RANGOON—When Burmese filmmaker Htun Zaw Win decided to make a short comedy about the tragically bizarre process of getting movies made in his oppressed homeland, he knew exactly what to base it on—real life.

“Ban That Scene!” makes a daring mockery of Burma’s dreaded film censorship board, whose members are cast as comical guardians of a tyrannical state’s idealized image of itself.

Sunk into the faux-leather chairs of a government screening theater, they face off against a sputtering film projector that bathes them in the dim reality of their own fallen nation. The officials are offended at everything that appears on screen—beggars, corruption, power outages, even a street fight—because they all allegedly make the state look “undignified.”

“Ban that scene! Remove it!” the bespectacled censor boss bellows over and over, jabbing an index finger through the twilit darkness with a triumphant, lips-pursed “hrrrrummph.”

Beyond its highly satirical take on modern day filmmaking in Burma, what’s most striking about the movie by Htun Zaw Win, who goes by the name Wyne, is that it was made at all.

Its existence, coupled with the fact that Wyne has seen no jail time, offers proof that some artists are growing brave enough to criticize the establishment as the nation’s new reform-minded government begins allowing a level of free expression that was unheard of here during decades of suffocating military rule.

But the film also proves just how much here remains unchanged. Wyne says he never submitted “Ban That Scene!” to the government’s Film and Video Censor Board for approval because they would almost certainly have, well, banned the entire thing.

The board’s mandate is limited to screening films made for sale, and Wyne says he chose to forgo all profit to ensure it would be produced uncut. The sacrifice was essential, he said, “to show the public both at home and abroad what barriers filmmakers are facing.”

The 18-minute short was first shown in the former capital Rangoon in January during a film festival dubbed “Art of Freedom” that was hosted by opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi and the prominent local comedian Zarganar.

It has been posted on YouTube and Wyne has so far distributed about 10,000 copies on DVD for free. But the movie’s impact has been limited. It cannot be shown in local cinemas, and the vast majority of Burma’s 60 million people are out of reach—living in thatched huts without electricity or internet lines in a rural countryside that’s remained almost untouched for hundreds, maybe thousands, of years.

Still, the work is remarkable for what it contrasts brilliantly throughout—on one hand, the sanitized image of Burma that the nation’s xenophobic former regime once wanted to portray to the world; on the other, the tumbledown reality of just how far this place fell under their rule.

In one scene, the main government censor’s eyes widen in horror as a disheveled, limping man appears on screen begging for money to look for a job abroad.

“That makes the state less dignified,” the censor growls. “If people abroad see it, they would think that beggars exist in Burma!”

When another bespectacled censor—acting as a muse of commonsense—timidly suggests that everybody knows beggars do exist here, the boss gives up only the slightest ground. They “just exist in real life! Not in this movie!”

In another sequence, the censors are taken aback when the power goes out during a love scene—an affront, they say, to the Ministry of Electricity.

When another official notes that outages are commonplace, the boss trumpets the government line—Burma is not short on power; it has so much, it has to sell it abroad. (The sad reality is around 75 percent of people here spend their nights in darkness. The country exports much of what it produces because so little infrastructure has been built to channel electricity to those who need it).

Amid the debate, the movie shows the screening theater’s lights promptly dying—by the time a generator sputters to life, the boss is snoring loudly.

Wyne, 39, said he has been surprised at the positive response to the film he has received from a few top officials in the country’s post-junta regime, which is made up largely of military officers who retired to join the civilian government.

Wyne said one told him: “This needs to be shown in public. People need to know what’s happening. Because if we keep banning scenes like this, we’ll have nothing left to watch.”

Wyne declined to identify the man or any others who’ve offered praise, however, underscoring the sensitivity of the subject.

The censor board itself could not be reached for comment. Zarganar, the comedian, called the satire “an important work” that shows artists are truly becoming independent again.

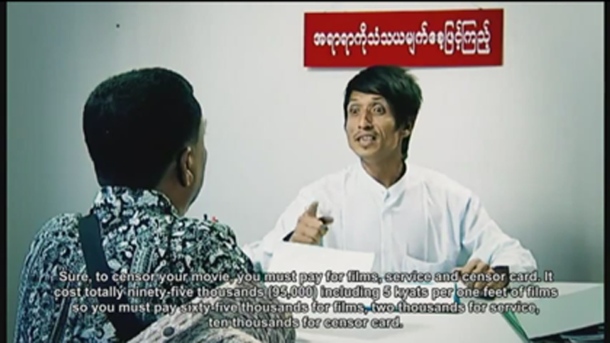

For now, though, getting movies made requires a lot of cash, and not just for production expenses.

Transparency International ranks Burma the third-most corrupt on Earth, and Wyne says that even banned scenes can be still get made if substantial bribes are paid.

In one of the movie’s final skits, the censors are aghast at a sequence showing a civil servant accepting a box of withered currency bills; their horror turns to delight when baskets filled with flowers and whiskey are brought into the screening room—a gift from a desperate producer.

Wyne ends the movie with three hopeful words: “We can change.”