BANGKOK—For almost three weeks, Ma Yamin has been volunteering to help her fellow migrant workers in Thailand fill in the required forms to register for early voting in Myanmar’s 2020 general election. At her home in Bang Bon district of Bangkok, the capital of Thailand, she welcomed them, took their details, filled in the forms correctly, and copied their passport to attach to the application. The Myanmar migrants would usually arrive at her house from early evening to around 10 p.m., after finishing their overtime shifts.

She is one of many other volunteers who help their compatriots complete such forms; some who help are individuals, some are groups like the Migrant Workers Rights Network based in Mahachai in Samut Sakhon province.

In contrast to the last election in 2015, after the Union Election Commission (UEC) announced that the election date would be Nov. 8 and that citizens based overseas could register for early voting, thousands of Myanmar migrant workers in Thailand began to mobilize to register for early voting.

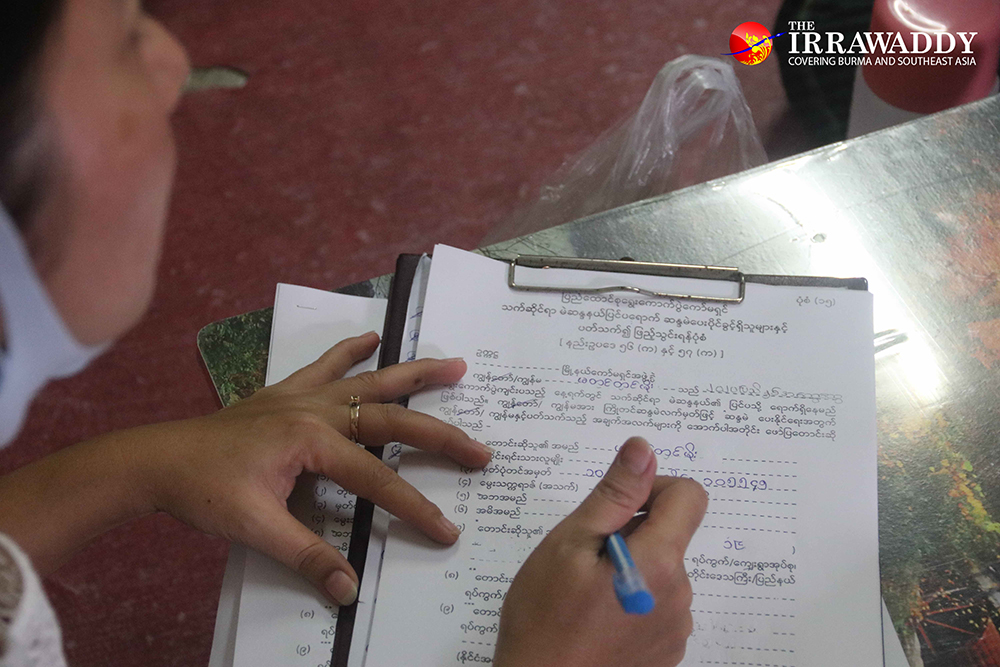

To register, eligible voters who are out of their constituency were required to submit Form 15 between July 16 and Wednesday.

“Here in Thailand many migrant workers in my community are interested in early voting, but they don’t know what to do or where to get the forms. They get information through their mobile phones. So I help them with the registration process,” said Ma Yamin, explaining why she offers assistance to those looking to register.

Not all migrants are interested in voting though. “Some are not interested,” she said. “They say they’re not interested in who is in power or what kind of government it is, because in the end they have to support their families. But I tell them we have to grab our chance to cast our ballots freely in the 2020 election.”

Ma Yamin cast an early ballot in 2015; she recalled there were difficulties at the time of registering as well as on the actual early voting day. She said the situation in 2020 is “very different,” as this time the Myanmar Embassy is sharing all necessary information transparently.

Embassy role

In 2015, only 561 Myanmar nationals—few of them migrant workers—registered to vote early from Thailand, according to the UEC, and they were only given one day on which to vote at the embassy in Bangkok. In 2015, around 30,000 overseas Myanmar nationals registered to vote early in 37 countries, with Singapore seeing the biggest turnout. In Thailand and numerous other countries, most of those who tried to vote found they could not. Some migrants said they only found out about early voting on the actual day (Oct. 17, 2015) and did not know how or where to request early voting. In the last election, the embassy failed to inform Myanmar citizens in Thailand or set up sites to cast ballots, essentially barring them from participation.

For the upcoming November election, the Myanmar Embassy has changed its tune. It informed Myanmar overseas voters in Thailand on July 3 that any Myanmar citizens who hold a legitimate document of identification, such as an ordinary passport, a passport for job type or a certificate of identification (CI), can apply for early voting for the 2020 general election.

The embassy used Facebook, which is the most widespread social media platform among Myanmar people, to share its information. Thanks to Facebook, many migrants with access to mobile data, 3G and 4G networks became aware about the voting and the need to check voter lists back home in their villages or townships in Myanmar.

To participate in early voting, Myanmar people in Thailand could register online, through the postal service or in person at the embassy in Bangkok or the Myanmar Consulate General’s Office in Chiang Mai, until today.

The Myanmar Embassy in Bangkok said in a statement on July 24 that depending on the number of peopled who register to vote in Thailand, it would announce the dates for early voting and the venues once all registrations had been checked and verified by the UEC.

The embassy urged citizens to register to vote early, saying it was their responsibility as well as their right. The embassy also released a list showing whose requests to register for early voting had been received correctly and whose needed changes. In this way, faulty applications can be resubmitted on time.

First-time voters excited

For some migrants who have been working in Bangkok, Samut Prakan or Samut Sakhon for more than 10 years, the 2020 general election will be their first experience of casting a ballot.

They did not have a chance to vote in the last general election, as at that time many migrants in Thailand did not know about the electoral information in advance.

Myanmar migrants in their 20s, 30s, 40s and 50s, and those who have been living and working in Thailand for 10 to 30 years, are making time to be able to take part in this election.

Most being factory laborers, their only day off is on Sunday, which makes it harder for them to submit the forms by themselves. Thanks to the volunteers and the labor rights organizations, forms for requesting permission to cast advance ballots can be obtained from the volunteers.

According to Thailand’s Department of Employment, there were over 1.15 million registered Myanmar migrant workers in the country as of August 2019, and an unknown number of undocumented workers. Since COVID-19 hit Thailand’s businesses, over 100,000 migrants returned to Myanmar, an initial group in March and then another group since May 23.

Thailand had a total of 2.79 million registered migrants from Myanmar, Laos and Cambodia in December 2019. Due to the unemployment caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, Thailand’s Department of Employment said that over 310,000 people had returned to their countries since March, but as of June, Thailand still hosted some 2.589 million migrants in its various business sectors.

“We get this chance to vote once every five years. This is my first time to vote, so I am excited,” said 24-year-old Ko Win Ko Oo, who took leave from work on Tuesday in Mahachai, Samut Sakhon province, to volunteer to help others submit forms.

He volunteered for others who could not get the day off and brought a dozen forms to the embassy. He has helped submit forms three times since July 22, said Ko Win Ko Oo, who is from Taunggu in Bago Region.

In the 2015 election, he could not cast a ballot, as he did not have an ID card. After the embassy issued him with a Certificate of Identification, a document provided to formerly undocumented workers in Thailand after a verification process, he went back to Myanmar, obtained an ID and obtained a passport in order to be able to work.

The Irrawaddy met a few individuals who were able to submit their forms to register at the embassy without the help of volunteers.

Ko Aung Naing Win, a 46-year-old Karen man, took a day off from his job in Samut Prakan on Tuesday to submit his Form 15 (an official request from someone who is outside their home constituency to vote in advance).

He has been working in Thailand for nearly 20 years and “never cast a ballot in an election”. He hopes to participate this time, he told The Irrawaddy after submitting his papers.

His hometown is Thanbyuzayat in Mon State, and he said his wish was for the people’s representatives to be elected and for the government to do good for the people.

He echoed others’ view that they “want to elect leaders who will change their lives and the lives of their generation.”

As of Monday, over 10,000 applications had been received, according to the Myanmar Embassy. The embassy has been sharing a list of those whose applications have been accepted and those whose applications need updating with further details on its Facebook daily since last week.

Ma Nyo Nyo Win, a migrant worker in Bang Khae, in the southern part of Bangkok, is another first-time voter.

On Sunday, she visited volunteers at the Mahachai-based Migrant Workers Rights Network, which helps send early voting forms to the Myanmar Embassy in Bangkok.

No interest in elections

While some are enthusiastic and happily give up their time on a Sunday—their only day off for the week—to participate in the electoral process, some other migrants, especially those from the ethnic states of Myanmar, said the election held no interest for them.

Sai Chit Ko Ko, 33, from Mon State’s Tha Hton Township, said he did not know anything about the election, and was not interested in casting a ballot.

One of the reasons for this ethnic Pa-O man’s lack of interest is that “they [politicians] come when they want the votes, but later they do not care about us. We ethnic [minorities] have not seen any [development].”

He has been in Thailand for 10 years and lost work for three months due to COVID-19, but he got a new job when Thai businesses were able to reopen. He said he would continue staying in Thailand like many others, as there are no job opportunities in Myanmar.

Ko Kyaw Oo, an ethnic Karen from Mon State’s Kyaikmayaw Township, said, “I want to cast a ballot, but it is difficult as I don’t understand politics.”

He went on to say that as he never had formal schooling, family survival is his top priority.

“I just want my country to be good. If the government did good things such as provide access to electricity and better road transport like other nations, it would be good,” he added.

Visiting his home on the outskirts of Mahachai in Samut Sakhon province, The Irrawaddy learned that even though there are some people who are interested in the election and voting, they had no way of applying to register to vote early due to limited time and knowledge. They saw the information on Facebook, but have neither the technical knowledge nor the equipment to print it out, and many lack the knowledge to correctly fill the forms and submit them at the embassy.

Although there is enthusiasm among the migrant workers about the election, their access to information about the electoral process is limited. But a few are well aware and are actively volunteering.

Some of those who register for advance voting incorrectly think that they have already cast a ballot, mistaking registration for voting.

“Migrant workers have little to no access to information; they spend most of their time at work and home. We are also volunteering based on the little knowledge we have. It would be good if there was more information sharing during the campaign period,” Ma Yamin said.

Not only in Bangkok, but also in other areas where many Myanmar migrants work, including Chiang Mai, Ranong, Mae Sot and Samut Sakhon, volunteers play a key role ensuring every migrant exercises their right to vote early.

In Mahachai, there are an estimated 400,000 Myanmar migrants working in factories, many of them in the seafood processing sector, but the number of people interested in the Myanmar election and early voting is low compared to the population of migrant workers, said U Aung Kyaw, the head of the MWRN.

MWRN office staff and volunteers have been distributing forms, helping migrants who are interested in voting to fill in the information correctly and submitting them on behalf of the constituents for three weeks.

U Aung Kyaw, himself a first-time voter, said Mahachai has many migrant workers and his group had helped submit more than 1,000 forms so that their colleagues would be assured of their right to vote.

He said that in the upcoming advance voting period, it would be better for migrant workers if the embassy could open an early polling station in Mahachai, rather than requiring the migrant workers to go to the embassy to vote.

However, it is not clear yet how the UEC and the embassy will decide on this issue—whether registered voters (once they are verified) will have to cast early votes at the embassy premises (or the Consulate-General’s Office in Chiang Mai), or whether the embassy will be able to arrange mobile polling booths in areas with high numbers of registered migrant voters.

You may also like these stories:

Ex-Aide to Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to Contest Election, but Not Under NLD