RANGOON — The floor of a grand but forgotten spiral staircase in a corner of Rangoon’s Secretariat office complex has been transformed with a large square of bright yellow pollen. Painstakingly collected by hand, the yellow powder stands out among the building’s faded paint, rusting steel, and weathered stone.

The installation is part of an exhibition by German artist Wolfgang Laib titled “Where the Land and Water End.” The conceptual artist creates large minimalist installations often using natural materials such as milk, pollen, beeswax, rice, and marble. To display his works, the Secretariat will open its creaky doors to the public.

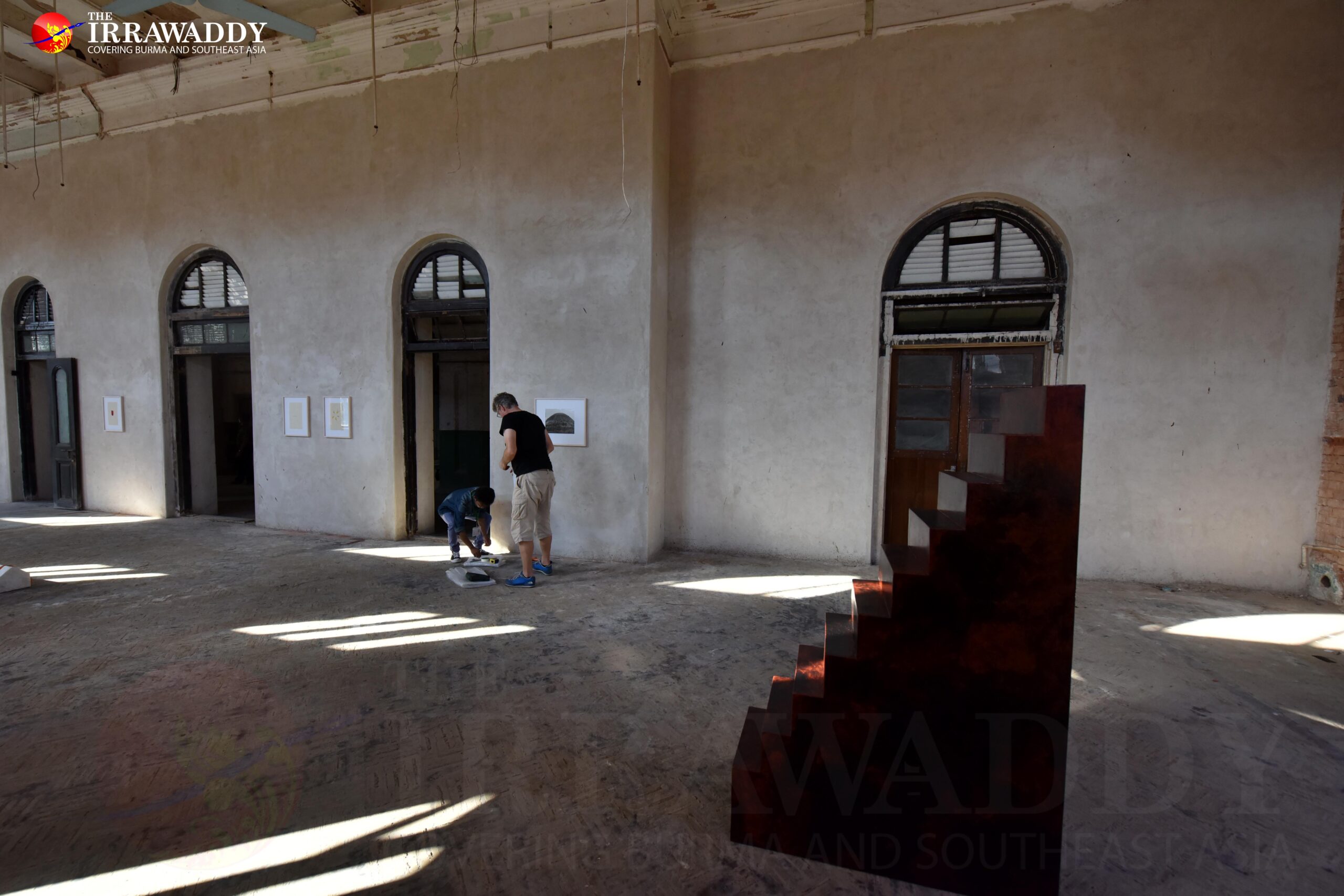

“I love this place, I love the rawness and the columns,” Laib told The Irrawaddy in one of the building’s large halls, to the soundtrack of cooing pigeons and Rangoon traffic. “It’s an honor, but it’s also a responsibility to put on an exhibition here.”

Four areas of the Secretariat’s southern wing are occupied by pieces created by Laib throughout his decades-long career. The exhibition is somewhat of a retrospective. At the top of the staircase is one of Laib’s “milkstones,” a large white marble shelf thinly covered in fresh milk. It was first created by Laib in 1977 when the artist was just 27 years old.

On a verandah overlooking the Secretariat’s inner courtyard, local rice is piled on a row of brass-colored thali plates from India—a piece Laib conceived in the 1980s. In the largest hall is a fleet of brass ships with rice piled around each one.

Germany’s Goethe Institut wanted to bring Laib’s work to Burma but knew it would have to find a space worthy of this artistic heavyweight—his 2013 exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art drew crowds of 10,000 a day, and in 2013 he won the Japanese art prize Praemium Imperiale.

The curator sent Laib photographs of the space, and, together with the German Institute for Foreign Relations, they resolved to make it happen. Navigating Rangoon’s red tape and bureaucracy was an art in itself—“It was never clear who had the say. It is all in transition here,” said Laib.

Installing the exhibition presented its own challenges. Accompanying the brass ships are larger versions sculpted in beeswax. In previous exhibitions, they perched on scaffolding above the floor. But with no air conditioning at the Secretariat, the risk of melting was deemed too high, so the ships sit firmly on the hall’s floor. Laib’s precious pollen, which he still collects every spring, will only stay for two days to minimize the chance of being contaminated by pigeon poop.

The challenges were not just bureaucratic and logistical. “To make an exhibition in such a building with such a history is a difficult thing,” Laib told The Irrawaddy. “We know that shootings and killings happened here,” he said, referring to the assassination of Burma’s independence hero Aung San and his colleagues in an office in the west wing of the Secretariat in 1947.

The artist showed an understanding of, and connection with, Burma, its history, and its people. Laib pointed to his fleet of brass ships and said, “in the past there were many ships in Rangoon—but they were war ships, or they were ships taking things away from this country.”

Laib’s sensitivity stems from a long association with the country. Another of his pieces on display is a large stairway in lacquer from Bagan—just some of the 100 kilograms the artist bought on a visit over twenty years ago. On the wall, a sketch titled “Botahtaung” depicts the shapes of Rangoon’s famous downtown pagoda in a fantastic pollen yellow.

Ten years ago, Laib even looked into setting up a studio in Burma, but instead settled for rural southern India. He now splits his time between India, his studio outside a small village in southern Germany, and Manhattan.

“I feel lonely, and I live a very lonely life as an artist,” said Laib.

Like his work, Laib is calm and reflective. He has spent a lot of his life studying eastern philosophies, including Taoism and Zen Buddhism. “My work is my meditation,” he said, “I don’t have to sit with my legs crossed.”

Laib wants his work to bring people together through beauty. He previously trained as a doctor but thought that art was more important. He said that Burma’s recent history and ongoing conflict make this exhibition even more significant. “When you look back at history, it is culture that brought humanity forward, not soldiers.”

“Art is not decoration,” he told The Irrawaddy. “I want to change the world.”

“Where the Land and Water Ends” at the Secretariat (entrance on Thein Phyu Road) runs from Jan. 14 at 2.30p. It runs between 10am and 5am every day until Feb. 4. The pollen installation will only be in place on the opening weekend.