If he were alive today, U Thant would be 109 years old.

Long before the country became known for military oppression and pro-democratic struggle, Myanmar (then known as Burma) made international headlines when, at the height of the Cold War, he took the highest position at the United Nations. As the third secretary-general of the United Nations from 1961 to 1971, the educator-turned-civil servant became the first non-European to hold the position.

During his 10-year-and-one-month tenure at the UN, U Thant criticized both West and East for actions and attitudes that he considered threatening to world peace. He helped defuse the Cuban missile crisis, which had brought the United States and the Soviet Union to the brink of nuclear war. He also helped end a civil war in Congo among other achievements.

U Thant died of cancer in 1974 at the age of 65. The Myanmar public viewed him and his contribution to world peace with pride, but this was not shared by the country’s former dictator Ne Win, who ruled Myanmar from 1962 to 1988. Ne Win never took U Thant seriously; he was envious and suspicious of U Thant’s local and global popularity. As a result, the former UN secretary-general was denied a state funeral, and his biography was excluded from school curriculums in Myanmar.

At the initiative of his grandson, Dr. Thant Myint-U, a writer, historian and the chairman of Yangon Heritage Trust (YHT), U Thant House, a museum dedicated to the life and work of the former UN leader, opened to the public in Yangon four years ago.

On the eve of his grandfather’s 109th birthday on Jan. 22, Dr. Thant Myint-U talks to The Irrawaddy about U Thant’s legacies, both globally and in Myanmar, his memories of his grandpa, what made U Thant a successful UN leader, and other topics.

What are your fondest memories of your grandfather when he was secretary-general of the UN?

I was 8 years old when he died. And I remember him very well, as we lived together in the same house outside Manhattan — my parents, grandparents and my little sisters. I remember swimming together in our pool at home, seeing him reading and writing in his study, watching cartoons on TV in his bedroom, a portrait of Mahatma Gandhi behind him. I remember only once visiting him at his office at the UN, and that was in 1969 when the Apollo 11 astronauts, including Neil Armstrong, came to see him, though I was so young I didn’t really know who they were.

He was a provincial school teacher and later served as secretary to then Prime Minister U Nu. How did he get to become the unanimously elected leader of the UN?

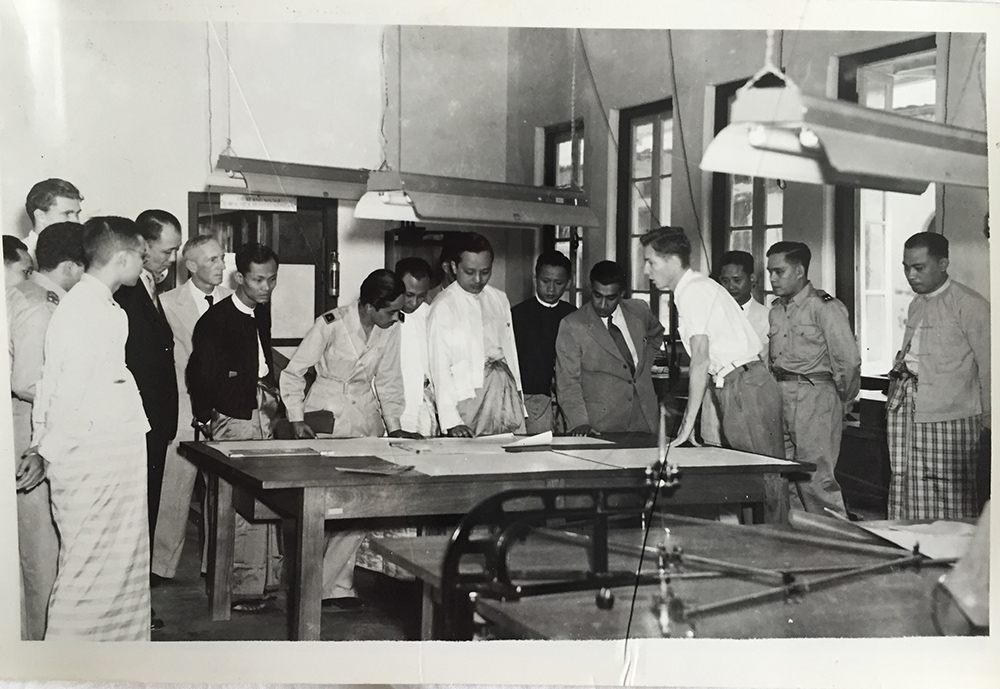

He arrived in New York as Burma’s Permanent Representative to the UN in August 1957. By the time Dag Hammarskjold, his predecessor, was killed in a plane crash four years later, he had already established himself as one of the more dynamic and capable diplomats in New York, chairing for example the Non-Aligned Movement’s committee on Algerian independence. He was very active on all decolonization issues and Hammarskjold, who believed the next secretary-general should come from the “Third World”, had identified him as one of two possible successors. “Third World” and “Developing World” were actually terms Hammarskjold and U Thant came up with together. Burma was then of course a neutral country in the Cold War and in November 1961 he emerged as the only person acceptable to both the Americans and the Soviet Union.

What do you think set your grandfather apart from other UN secretaries-general?

He was the first non-Westerner ever to hold a senior international position. He was the first person from a recently decolonized country to lead world debates on peace and development. In many ways he continued the seminal work of Dag Hammarskjold. And he depended very much on the Nobel Laureate Ralph Bunche, the African-American civil rights leader who had been Hammarskjold’s key deputy, as well. But a difference was that he brought to the top job the perspective of the very young governments of Asia and Africa; many like Burma, [were] then desperately trying to hold their countries together. He placed great importance on development cooperation, setting up the UNDP and many other funds and programs. He placed great importance on human rights, saying that nothing was more important than “individual human dignity.”

Defusing the Cuban Missile Crisis and ending the civil war in Congo are U Thant’s milestone achievements as secretary-general. In your opinion, what qualities allowed him to handle those successfully?

His personal courage and integrity were very important. He did what he thought was right and took responsibility for his actions, never blaming others. People knew they could trust him and trust that he was acting on behalf of the principles of the United Nations and nothing else. And he knew to take the advice of those more experienced and knowledgeable than himself on many issues. He was a good listener and he delegated authority to his many capable aides, like Ralph Bunche. I think he was also a person who was at peace with himself, with a clear mind, who could go home at the end of the day, swim, watch TV and have dinner with his family.

How much do you know about the relationship between U Thant and the late General Ne Win? Why did their relationship turn sour?

They of course knew each other well in the 1950s but they were not particularly close in any way. General Ne Win had a good trip to the UN in 1965 on the sidelines of his visit to President Johnson in Washington. I think the relationship soured in the late 1960s after U Nu set up his government in exile with the aim of overthrowing the Revolutionary Council, and General Ne Win suspected U Thant was colluding with U Nu. U Thant and U Nu had of course been close friends since university days.

As secretary-general, he was of course restricted from being involved in any way in Burmese politics, but he did meet U Nu when U Nu came through New York in 1968 and spoke to journalists at the UN Correspondents Club, calling for revolution. I’m sure General Ne Win was not happy.

What are his legacies for the world and Myanmar today?

His role during the Cuban missile crisis was indispensable, and helped bring the world back from the brink of nuclear war. There were many other successful mediation efforts, some so successful, for example in Yemen in 1962 and Bahrain in 1968, that barely anybody remembers them today. He made development a key focus of international cooperation. And he brought environmental issues front and center, speaking out against what he saw even then as the destruction of the planet.

In Burma he represented a liberal tradition that has since almost disappeared. And as Burma’s ambassador to the UN he showed that this was a country that could make a real contribution on the international stage.

If he were alive today, what would be his contribution to rebuilding our country?

Well, he would be extremely old, so I hope he would just be retired and enjoying life. If things were different and he was still alive but somewhat younger, I think he would first and foremost be a voice for “individual human dignity,” apart from issues of ethnic and group identity and politics. He would also be a strong advocate of education. I’m sure he would see any progress towards democratic government depending largely, if not entirely, on progress in education. He would doubtless be heartbroken to see the violence that has taken place and continues to take place in Burma and to see so many in the country still so poor at a time when Asia was becoming so prosperous. And he would have spoken out very clearly on the importance of a free and spirited media.

Given the situation Myanmar faces today at the international level, how would he respond if he were at the UN now?

I’m not sure. On the one hand he increasingly saw himself as a global citizen and wanted people to rise above nationalism and understand the importance of global cooperation, of finding global solutions to problems. On the other hand, as someone who had lived through colonialism and had worked in a post-independence government, I don’t think he would have been an interventionist, or at least he would have seen the limits of outside intervention. He would likely have placed a high value on quiet diplomacy, a quiet search for how the UN could be useful.