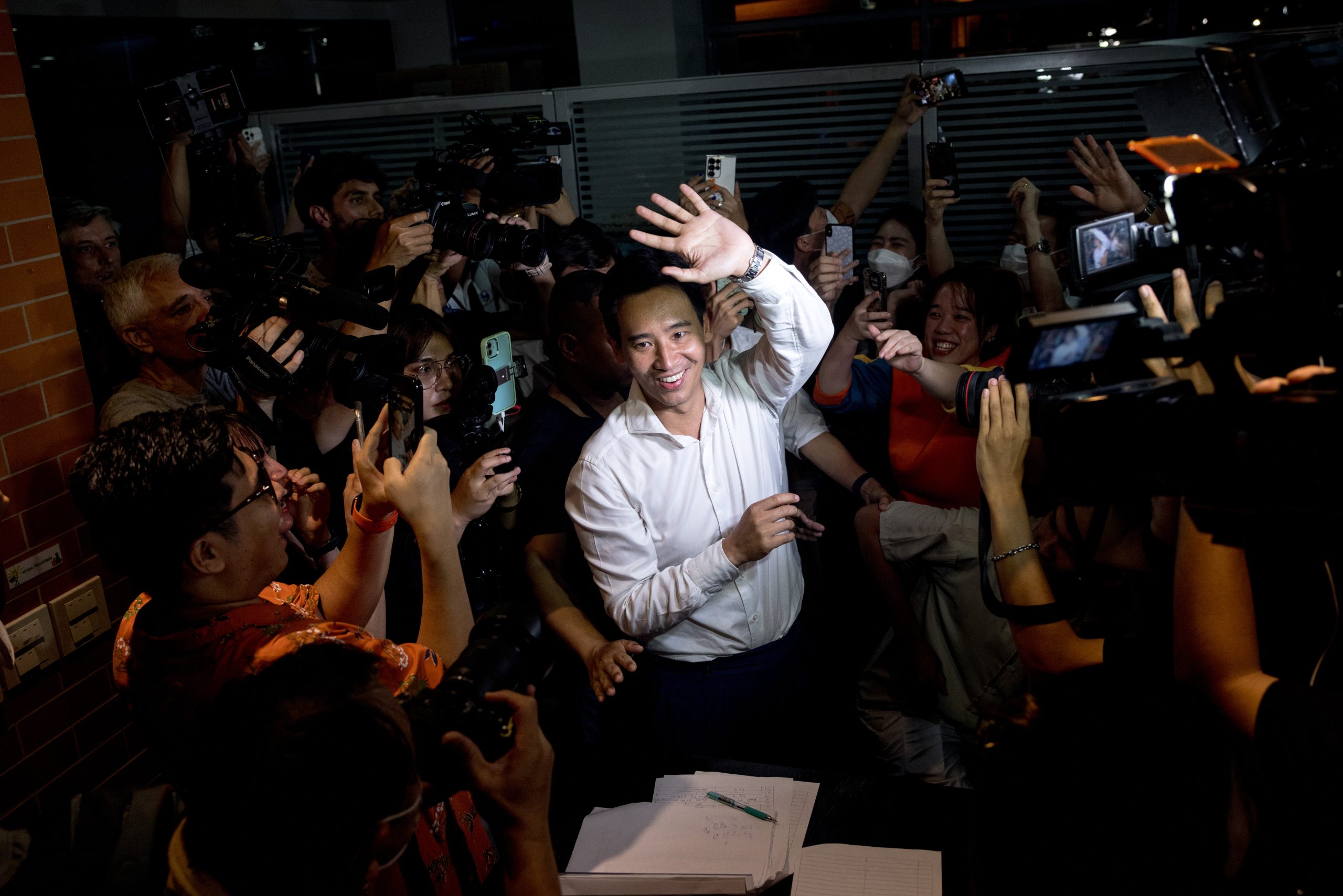

The possibility of Thailand getting a new, democratically-elected government which is not a military proxy has raised hopes of a fresh and more sympathetic policy towards the forces in Myanmar that are fighting against the junta in Naypyitaw. Pita Limjaroenrat, the leader of the Move Forward Party which gained the most votes, has been a consistent critic of Bangkok’s policy towards its western neighbour. He said only two days after the May 14 Thai general election that Thailand should make sure that the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Five-Point Consensus peace plan is implemented, with the first and most urgent task being to establish a “humanitarian corridor” between Thailand and Myanmar.

Pita also said that Thailand should work together with the international community and referred to the Burma Act, which was passed by the United States congress after the 2021 coup and authorizes humanitarian assistance and civil society support, as well as promoting democracy and human rights in Myanmar. The right amount of pressure and incentives should be applied, Pita said. Pita’s foreign affairs chief, Fuadi Piysuwan, went even further and said on May 23 that Thailand should move from pursuing old-style “quiet diplomacy” to playing a more active role in dealing with problems confronting the region, especially the crisis in Myanmar.

The Five-Point consensus, which was agreed upon by all ASEAN members at a meeting in Jakarta on April 24, 2021 and calls for “an immediate cessation of violence in Myanmar and constructive dialogue among all parties”, has turned out to be a non-starter. The military regime in Naypyitaw has simply ignored it, and there is no mechanism through which ASEAN can implement its various agreements and recommendations. Traditional Thai diplomacy has also proven fruitless. But the question of a humanitarian cross-border corridor could be a game-changer, as it would involve activities on the ground.

But there is a problematic issue that is often overlooked by most outside observers. When it comes to matters of national security, which includes relations with Thailand’s immediate neighbors, the Thai military has always been is in charge and the foreign ministry in Bangkok may not even be fully aware of what was and is happening in sensitive border areas. An early example would be the fate of the Nationalist Chinese, Kuomintang forces which after their defeat in the Chinese Civil War retreated first into northeastern Myanmar and then settled in northern Thailand.

They established a string of bases in the border areas from where they launched raids into China. Their stated, long-term purpose was to retake China from Mao Zedong’s communists but when that failed they turned their attention to the Golden Triangle opium trade. The Thai authorities ignored that, and even benefited from it, because the Kuomintang’s forces acted as a buffer between Myanmar and Thailand and, at the same time, collected useful intelligence from across the borders. They also brought in vast amounts of money which was reinvested in the Thai economy.

In the late 1960s, the Kuomintang army was transformed into Chinese Irregular Forces (CIF) and placed under the supervision of a special task force codenamed 04 which was controlled by the military’s supreme command in Bangkok. Connected with that effort was an outfit called the Free China Relief Service, which supplied Chinese-language schools in CIF settlements with textbooks and other learning aids from Taiwan. That was never official policy, and the clandestine scheme continued long after Thailand in July 1975 derecognized the Republic of China (Taiwan) and established diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China. The government in Bangkok also had little to say when the military brought in CIF troops to fight against the insurgent Communist Party of Thailand (CPT). Without the active participation of the CIF, the Thai military would never have been able to conquer the CPT’s military headquarters at Khao Kho-Khao Ya in 1981.

Thailand has always had cordial diplomatic relations with its ASEAN partner Malaysia, but even there it is possible to discern the difference between the official foreign policy and the one conducted by the military’s security agencies. The Thai military permitted the outlawed Communist Party of Malaya (CPM) to have camps in jungles in the far south of Thailand as long as they collected intelligence on Pattani Muslim separatists, who had bases across the border in northern Malaysia. Significantly, when the CPM in 1989 eventually decided to lay down arms, it happened in Thailand and the party’s leaders, including its legendary chairman Chin Peng, signed separate peace agreements with Thailand and Malaysia — in the southern Thai city of Hat Yai. Chin Peng, though, was never allowed to return to Malaysia. He remained in exile in Thailand and, on September 16, 2013, died at the age of 88 in Bangkok. He was cremated there according to Buddhist rites.

In more recent years, the Pha Muang Task Force has been responsible for overseeing Thailand’s northern borders with Myanmar and Laos, while the Naresuan Task Force was put in charge of Myanmar border areas further to the south. Both are under the command of the Third Army Region of the Thai military and operate without any noteworthy governmental oversight and accountability.

There are also other interests and actors in those border areas. It would not have been possible to build all the casino enclaves, which in the last few years have emerged opposite the border town of Mae Sot, without solid contacts with local business communities and law enforcement agencies on the Thai side. Construction material, machinery and equipment have been brought across the Moei River, which marks the border between Myanmar and Thailand, and into areas controlled by local militia forces which are allied with the Myanmar military.

There is little doubt that Pita stands for democratic values, but that could also be his downfall. Thailand’s generals have time and again shown that they are willing to intervene when the outcome of an election, or some other development, has not been to their liking. Since the absolute monarchy was abolished in 1932, the Thai military has staged at least a dozen coups and the country has had 20 charters or constitutions. The most recent constitution was adopted in 2017, and gives the military unprecedented power over the elected assembly. The House of Representatives with 500 members is elected while the 250 members of the Senate are directly or indirectly appointed by the military.

In some ways, that resembles how Myanmar was governed prior to the 2021 coup. There, the military appointed a quarter of all seats in the upper and lower houses as well as in regional assemblies. In that way, the Myanmar military had the power to block any attempt to change or amend the constitution it had drafted. In Thailand, a majority of 376 out of 750 seats is needed to elect a prime minster and form a government. Move Forward with 36.23% of the popular vote got 152 seats, and will have to find several coalition partners in order establish a functioning government. And even if Pita’s party succeeds in doing so, a “silent coup” could be launched to unseat it.

Move Forward is a de facto successor to the Future Forward Party, which became popular especially among young voters and won altogether 81 seats in the March 2019 election. The charismatic leader, Thanathorn Saengkanokkul, was suspended from his parliamentary post over his alleged illegal holding of shares in a media company and the party was dissolved in a Constitutional Court ruling on February 21, 2020. It was alleged that Future Forward had violated election laws regarding donations to political parties.

Something similar could well happen again if the military wants to get rid of Pita, not immediately — which would look bad given the outcome of the election — but later. And the process may already have begun: the Election Commission is expected to rule whether he is eligible to take part in an election due to his alleged ownership of shares in a media company. The military believes that it has to protect what it sees as “national security”, and would not want to see any attempt to interfere with its handling of border issues. Powerful economic interests will also be plotting behind the scenes to make sure that their cordial partnerships with the Myanmar junta, and the businessmen who are connected with it, remain unchanged and unchallenged.

Thai diplomacy in all its glory and pledges by the winners of this year’s election may in the end have little impact on the situation on the border between Thailand and Myanmar. If a humanitarian corridor against all odds was established it is unlikely that any civilian institution, elected or otherwise, would be able to influence how it would be run and managed. On-the-ground realities — strategic, political and economic — will most likely override concerns about democracy and human rights.