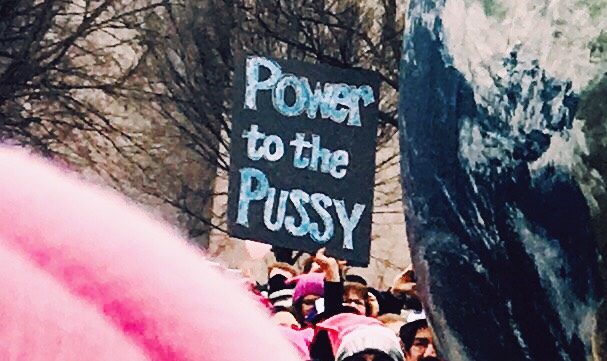

Last week, as I peered over a sea of pink hats at the Women’s March in Washington DC, one poster caught my eye. Next to a gigantic papier-mache earth was a sign, distant, but discernable, hoisted high into the air by a fellow demonstrator whose face I could not see. It read: “Power to the Pussy.”

The United States is still reeling from the misogyny that came fully to the surface in reaction to its first female presidential candidate, Hillary Rodham Clinton. In one meme that was circulated during the election, a picture of Clinton was placed on a large bucket of Kentucky Fried Chicken. It read: “Hillary Meal Deal; 2 fat thighs; 2 small breasts and a bunch of left wings.” Feminists pointed out that Clinton’s candidacy had resulted in a “sexist backlash,” bringing into bold light the “internalized misogyny” that still existed in the US. The sea of pink “pussy hats” that I swam through during the Women’s March was meant to reclaim that word—and its power.

The history of gender equality and women’s empowerment—or “pussy power”—in Burma is long and complex. Christian missionaries and colonial administrators were impressed by the liberated Burmese woman and her high status. Melford Spiro, the famous anthropologist, wrote: “Burmese women are not only among the freest in Asia, but until the relatively recent emancipation of women in the West, they enjoyed much greater freedom and equality with men than did Western women.” Burmese women enjoy social and legal equality with men, including property, inheritance, divorce, and voting rights.

The representation of the Burmese woman as high status was overturned only in the last two decades. Historian, Chie Ikeya, claimed that accentuating Burmese women’s privileged status was an anti-colonial strategy. Progressive thinkers emphasized Burmese women’s high status so that they could then point to its erosion under colonialism. Ikeya went on to interpret the status of Burmese women in relation to other colonial and orientalized subjects—mainly East and South Asian women. Ikeya positions Burmese women such that they are understood entirely through the lens of others. Rather than acknowledging the legal and social equality enjoyed by Burmese women as historical facts—worthy of analysis in their own right—she dismissed the very representation of the free Burmese woman as a form of fetishistic orientalism. The image of empowered Burmese women—equal to their men in most ways that mattered—was buried.

What emerges as even more puzzling than the dismissal of native forms of gender egalitarianism and female empowerment by scholars like Ikeya is the reintroduction of both these concepts by international NGOs. From 2011 to 2015, foreign NGOs led hundreds of workshops in Burma on women’s empowerment. One women’s conference in Rangoon kicked off with a video message by Angelina Jolie, offering words of encouragement to Burmese women. Participants at another workshop drew pictures of their own vaginas. That Burmese women have always enjoyed legal rights for which millions of women on this globe are still fighting was not discussed. They had rendered the notion of the equal and independent Burmese woman to be untrue—recasting her as oppressed—so that she could then be re-liberated by white women.

The same observations can be made of the West’s relationship with Aung San Suu Kyi. If the test of true female empowerment in a society is how people—both men and women—emote towards their female leaders, then Burma passes with flying colors. Even after Clinton had won the presidential nomination and the public was dependent upon her victory to overthrow Trump, Democrats were still wondering out loud whether Hillary was “likable.” With Aung San Suu Kyi, there is very little ambivalence. An unwavering majority of the Burmese public feel a deep sense of love and awe towards her. That awe—sustained for twenty-seven years—resulted in a landslide victory for her political party last November.

Western journalists embraced Aung San Suu Kyi as a prisoner of conscience; but since her release in 2010, she has been represented in Western media in the same disparaging manner as Clinton. Aung San Suu Kyi’s image survived the junta’s propaganda machine, but was being immolated by Western misogyny.

Even the Burmese word for pussy was buried by the deluge of overly general and largely inadequate observations made by foreign NGOs and journalists. In 2015, the Guardian published an article declaring: “In Myanmar there are no vaginas.” They went on to explain that there was no word for “vagina” in the Burmese language. The author claimed that this “verbal taboo” hampered progress towards gender equality. While it is true that there is no direct translation for the medicalized term “vagina” (the closest word is borrowed from the Pali term yoni or yoni magga), Burmese women have always spoken about their pussies.

Indeed, the Burmese word sauk (derived from saukpat, translated as “pussy”) is widely and frequently used in colloquial Burmese. Sauk is impolite, most often used as a profanity, but it is no more vulgar than the English terms pussy or cunt. Burmese speakers use sauk more often and apply it more broadly than English speakers use the word pussy. The term sauk is more flexible than the word pussy because it can be used as both an adjective and adverb, much in the same manner that the “f-word” can be placed as a modifier in front of other words in American English. Unlike pussy, which is only used in the States to belittle females or to belittle males who are thought to behave effeminately or cowardly, sauk is applied across situations and persons. The two most common insults that you can direct at someone is to call them a sauk-kaung or sauk-kaungma (translated literally as “pussy-man” or “pussy-woman”). The Burmese favor this insult over jerk or bitch.

Women do not skirt around the word either; they own it. During his fieldwork in Burma during the 1960s, Spiro observed that women used the term freely. He describes an elderly woman telling a neighbor to “eat (her) pussy” because he took a piece of jaggery; and when a girl was teased about a sweetheart by a group of young men, she retorted: “I wouldn’t rub him with my pussy.” An insult that only women can use is: “I will raise my skirt as a flag”. Brown wrote in 1915 that it was normal for Burmese women to drop their sarongs (tameins) during verbal altercations, grab their crotch and “hurl a rude invitation at (their) adversary.”

We can only delve into deeper discussions about gender and power in Burmese society when we move past the idea that Burmese women’s experiences parallel those of white women. Along with this realization, it is time we unearthed the buried image of the high status, liberated Burmese woman, not because we should valorize or romanticize any one culture, but because more than ever—not only in Burma, but in the US—we need new models of how men and women should emote towards female power. And for Burmese women, unearthing that buried image can perhaps help them to realize that rather than trying to create a Burmese word for vagina, they should continue—as they always have—to talk about their pussies.

Seinenu Thein-Lemelson, Ph.D. is a Burmese-American psychological anthropologist and postdoctoral scholar at the University of California, Berkeley. You can follow her on Twitter @SeinenuTL