After Myanmar’s military regime staged a bloody crackdown on the pro-democracy uprising in August 1988, many of the country’s democracy activists fled to the Thai border.

As armed conflicts intensified in ethnic areas over the years, war refugees and economic migrants also left for Thailand, which became a base for Myanmar’s democracy activists, ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), political parties, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and exiled news agencies.

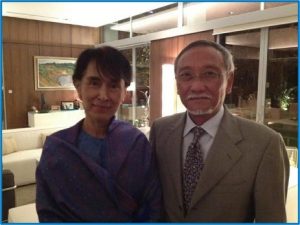

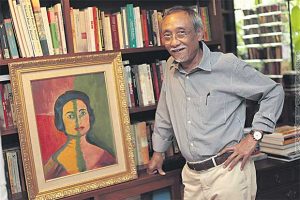

Myanmar democracy activists and EAOs based in Thailand must engage with Thai military and civilian officials. Kraisak Choonhavan, who died of cancer on June 11 at the age of 72, was one such official, but he was different from the others. Despite his upper class background, he dedicated his life to tackling the issues of Myanmar war refugees, migrant workers and human rights. It is fair to say that he was known by every Myanmar democracy and human rights activist based in Thailand.

Out of respect, Myanmar activists based in Thailand addressed him as “Saya”. The only son of former Prime Minister and General Chatichai Choonhavan, he was educated in Britain, France, Switzerland and the United States. He was well known in Thailand as a lecturer, political party leader, senator, environmentalist and activist.

Kraisak was long a staunch supporter of the causes of democracy and human rights in Myanmar, and was never hesitant to voice that support, both inside and outside the Thai parliament. Thanks to him, the Thai people, including business owners, political parties and military officials, learned about ethnic issues, refugees, human rights and political problems in Myanmar.

His faith was strong, though his heart was tender. Despite his high social status as an educated member of the Thai senate, he stood up for the vulnerable and underprivileged. And he was so approachable. His door was always open to visits from democracy and human rights activists.

His efforts on behalf of Myanmar migrants in southern Thailand in the aftermath of the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004 is engraved in my heart. Among the thousands of people killed in Thailand by the tsunami were hundreds of Myanmar migrants. Though the Thai and foreign survivors received proper help from the Thai government and their respective embassies, thousands of Myanmar migrant workers were arrested and sent back to Kawthoung on the Myanmar border. Thousands more were forced to hide in rubber plantations and forests, struggling to survive. One migrant whose leg was injured in the tsunami had to have the limb amputated, as he dared not go to a hospital for fear of being arrested.

When I told Kraisak about it, his heart went out to all Myanmar migrant workers. Immediately, he made phone calls and sought help from the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand. Thai police stopped arresting the migrant workers and aid was arranged for Myanmar tsunami victims.

I shared many unforgettable moments with him.

In 2000 I founded the Foundation for Education and Development (FED)—previously the Grassroots Human Rights Education and Development Committee—in the border town of Sangkhlaburi in Thailand’s Kanchanaburi province to assist Myanmar migrant workers with issues relating to education, health and labor. Like other illegal Myanmar organizations in Thailand, the FED ran into numerous problems and troubles.

There were frequent confrontations with Thai authorities and businesspeople, and in some cases, FED officials were arrested. So, I decided to officially register the FED with the Thai government so that it could be based inside Thailand and help Myanmar migrant workers and provide long-term support for refugees along the border.

For an NGO to register in Thailand, it must have Thai citizens on its committee. We therefore requested Thai activists with whom we had ties—and who were interested in the causes of democracy and human rights in Myanmar and were willing to help us—to serve as FED committee members.

Though Kraisak and I were known to each other, I was reluctant to ask him to join the FED because of his family background, reputation and social status.

However, Kraisak nodded willingly when his close colleague, the US documentary producer Jeanne Marie Hallacy, asked him to chair the FED.

And he did not lead the FED in name only, but played a major part in designing the organization’s policies for sustainable development. He also built up local and international contacts and helped raise funds. The FED became the first Myanmar NGO to register in Thailand.

For children, he had a genuine love. I once witnessed him fly into a rage upon learning that children of undocumented Myanmar migrant workers in southern Thailand were being denied schooling and security rights.

The FED today bears witness to his leadership, under which it developed to promote the rights of Myanmar migrant workers and provide education for their children.

He believed that the Myanmar migrant workers charged in the Koh Tao and Ranong murder cases were unfairly prosecuted, and used his contacts to help the defendants get whatever assistance was possible. He helped arrange meetings with officials of the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand at his house.

Kraisak was diagnosed with tongue cancer in 2015. His passing last week was reported in both local and international media.

This article is a tribute and expression of gratitude to Kraisak, who dedicated his whole life to the causes of democracy, human rights, ethnic war refugees and migrant workers from Myanmar.

Rest in Peace, Kraisak!

U Htoo Chit is the executive director of the Foundation for Education and Development, which supports Myanmar migrant workers in Thailand.

You may also like these stories:

How Will Millions of Myanmar Migrant Workers Vote in the 2020 Election?

Long Way to Go but Marching to It: 20 Years of Pushing Political Reform in Myanmar