Karen language education is still strong in the Thai-Myanmar border regions. There are currently over 130,000 children being educated in Karen schools operated in Myanmar by the Karen National Union (KNU) and the Karen Refugee Council (KRC) in Thailand. These schools are taking advantage of mother tongue-based principles of literacy, which emphasize that literacy starts with the home language. Since the 1980s at least a million people have completed the basic Karen curriculum focused on Karen literacy, with many of those continuing to secondary and post-secondary education where programs are taught in Karen and English.

Karen language education continues despite the marginalization of Karen schools in Myanmar since Ne Win’s 1962 coup. At that time, Karen schools in the Delta Region were replaced with Burmese language schools from the Burmese Ministry of Education. Since then Karen systems of education have remained strong in border areas outside control of the government. Indeed, Karen programs may have even strengthened after many government-funded schools were shuttered following the emergence of the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) in 2021.

Karen education is strong because, in part, it moved into Thailand, where schools continue both in refugee camps, and in migrant schools. The Karen language instruction in Thailand is typically organized by the KRC, which also provides support to schools still operated by the KNU inside Myanmar. The Karen schools in both places reflect Karen education traditions inherited from the Karen schools in Burma, which began in the 19th century. They do this while using teaching techniques and pedagogy adapted from the West, which train students to be “critical thinkers” for a Karen democracy.

Development since the 1840s

Karen education actually began in the 1840s with the development of modern Karen literacy, the establishment of a printing press, and the emergence of schooling. The earliest efforts were in the Irrawaddy River Delta and Rangoon (now Yangon). This led to a rapid expansion of the Karen school systems over the following decades. Karen and English language programs flourished around the large Christian mission compound in Bassein (Pathein, the capital of Ayeyarwady Region) in the Irrawaddy River Delta, as well as in Rangoon.

Baptist Mission primary schools among Karen were first opened by American Baptist missionaries in 1852 at Bassein. A Karen secondary school was opened in Koesue in 1854. The Karen Baptist Theological Seminary was already established in 1845 in Rangoon to train pastors literate in Karen and English.

The Bassein Sgaw Karen Normal and Industrial Institute taught English, Bible, Mathematics, Geography, History and Health, along with 19th-century vocational subjects like carpentry, joinery, wheelwrighting and rice production. There is no indication that Burmese language was a medium in the Karen schools, except as a subject.

After 1962, Karen schools declined when Ne Win’s government nationalized the Karen schools, and insisted on a “Burmanized” curriculum emphasizing Burmese language, history, and nationalism. Karen teachers trained in Karen Teacher Colleges were replaced with Burmese-speaking teachers trained in government colleges. Mother tongue-based Karen language instruction moved into the highlands, where independent schools were re-established by the KNU. After 1984 Karen schooling also moved into refugee camps in Thailand supported by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and international NGOs.

Independent Karen school systems emerge

The KNU resisted Burmanization by establishing their own schools. The education systems they established favored, preserved and reproduced Karen language and culture under difficult circumstances. In this fashion, Karen education survived, even as Karen education declined in the Irrawaddy Delta and the capital, Rangoon.

This did not stop Myanmar’s military from trying to spread their control into the mountains. In 1995-96 the KNU capital at Manerplaw was captured. The Karen Education Department (KED) continued to operate schools inside Burma, even as the Karen Refugee Committee—Education Entity (KRC-EE) based in Mae Sot, Thailand, became more important. Ironically this strengthened the Karen schooling system because it put the school system into contact with international organizations interested in educational reform. Once established in the 1990s, the KRC-EE reevaluated how modern pedagogical approaches would be used effectively. Young Karen teachers studied these techniques in the United States, Australia and Canada, and then returned to implement programs in the refugee encampments and in Mae Sot. The programs were successful, and soon refugee schools received not only Karen students from KNU controlled areas of Myanmar, but also ethnic students from Yangon, Ayeyarwady and Tanintharyi seeking a Karen and English media curriculum.

Karen education in the border region today

The KRC’s Education Entity developed the Karen curriculum by adapting the older KNU-KED curriculum, which in turn, was based on the Karen curricula developed in 19th-century Burma. The primary and secondary curriculum lasted 12 years. Notably, this is longer than Myanmar’s system, which lasts 10 years. Pedagogical techniques emphasizing critical thinking were introduced in a post-secondary training system which emphasizes secular teacher training, and the development of church leaders. The refugee camp schools had a simple advantage in the development of Karen education because they were not subject to attacks by the Myanmar military, as were the schools in Myanmar itself.

Refugee school curriculum

Since 2008, the refugee camps’ education system has been standardized with new curricula designed and supported by Karen education stakeholders and international nongovernmental organizations. The KRC Education Entity curriculum adopted student-centered pedagogy to replace the rote learning methods traditionally used in Burma. Karen is the medium of the schools, and English is taught as a subject beginning at the primary school level. Consistent with mother tongue-based education principles, the Burmese language is taught as a subject but not as a teaching medium. The Thai language is also occasionally taught in some schools as an elective. The Karen leaders in the camps encourage Burmese language, but not surprisingly, most young refugee students resist learning the Burmese language, which is viewed as a tool of domination.

In 2015 KED published an education policy with the following four basic principles. Notably, it leaves out references to national boundaries, but reflects values found in many national and statewide curricula around the world.

*Every Karen shall learn his own literature and language.

*Every Karen shall be acquainted with Karen history.

*The Karen culture, customs and traditions shall be promoted.

*Our own Karen culture, customs and traditions shall be made to be respected by the other ethnic nationalities, and the cultures, customs and traditions of the other ethnic nationalities shall mutually be recognized and respected.

At all levels, Karen history, literature, poetry and world history are taught.

Sensitive subject

Karen history is perhaps the most sensitive subject taught from the Burmese perspective. Karen history describes how the Bamar culture and its kings dominated and enslaved the Karen before the arrival of the British. The British arrival in the 19th century is described in the Karen history books as a liberation from Burmese domination, which permitted the re-emergence of indigenous Karen culture.

In contrast, Burmese history, first created by Ne Win’s Education Ministry, teaches that the Karen are rebels and a threat to national unity, particularly in the context of the highly centralized government structures insisted upon after 1962. Burmese history textbooks refer to Britain as an external enemy that sought to destroy the country and describes the British as imperialists, collaborators and as “stooges.” Karen history textbooks teach about the positive legacy of the British parliamentary system, and the American education system on which the missionaries first based the Karen education system.

In addition to Karen being the medium of instruction in primary schools there are other contrasts. A few examples from the Karen curriculum.

- Karen poetry (Hta)—Karen poetry is studied from Grade 6–8 in the Karen subject. The writing style of the Karen essay is studied, drawing from Karen Hta literary styles. Beginning in Grade 8, the varieties of Karen Hta and its interpretation are reviewed. In Grade 9 and 10 of the Karen subject, different classifications of Karen Hta and its history are studied.

- Aung San—General Aung San is not specifically mentioned in the Karen history curriculum and is mentioned only in a brief history of the Burmese revolutionary movement. The conflict between the Burmese Independence Army (BIA) commanded by General Aung San and the Karen during World War II is described in Grade 7 History, including the massacres of Karen undertaken by combined Japanese and BIA forces.

- Saw Ba U Gyi—Saw Ba U Gyi is studied in Karen school in Grade 6 and Grade 10 as the national hero and father of the Karen nation. In Grade 6, Saw Ba U Gyi’s biography is also studied in both Burmese and Karen subjects. Saw Ba U Gyi’s own writing is studied in Grade 10 and 11 in Karen History. Since Saw Ba U Gyi’s writing was originally in English, the Grade 10 and 11 materials about him are taught in English.

- Religious diversity—This is studied in grades 6, 7, 9 and 10 of Social Studies. In grades 6, 7 and 9, it is studied in the Karen language, and English in Grade 10 is in English. The importance of religion and the religious diversity of Burma, including Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism are studied.

A shared consciousness has emerged among Karen crossing international boundaries “rhizomatically,” as refugees grew up in the camps and in the diaspora, including many who have no personal memories of Myanmar. Ironically, refugee children born in the temporary camps consider the Karen diaspora and Kawthoolei their nation, even if such a place exists on no international maps. In this context, the Karen language thrives. The popular Karen-language film and music production scene serves Karen youth and has a substantial audience on YouTube and other social media.

The persistence of Karen education in the highlands of course creates a conundrum for any future Myanmar government seeking peace. The divergence of the Karen, Burmese and Thai curricula long ago created what social scientists call a “national consciousness” among the Karen of the Thai-Myanmar border region. This consciousness is about their identity as a people, and presumes a level of cultural and political autonomy. Talks about federalism in past decades assumed this autonomy, but of course negotiations were unsuccessful. So there remain tensions between the 130,000-plus children being educated in Karen-medium schools, their families, and the demand of Myanmar’s Bamar-dominated military government for one disciplined nation under military control.

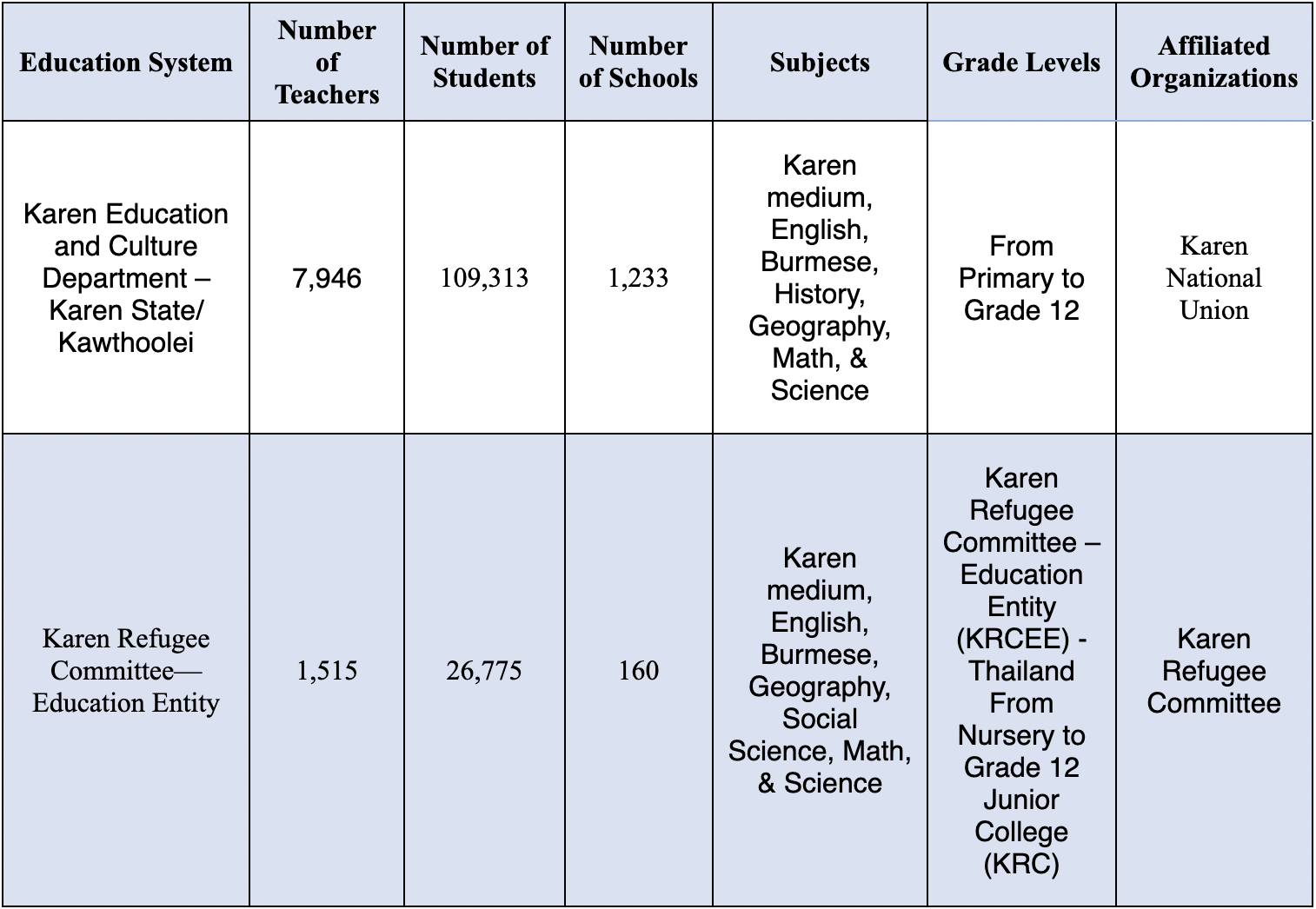

Table 1—Karen Medium Schools in Burma and Thailand, 2022

(Source: KECD 2022; KRC-EE 2022)

This article is adapted from “Schooling, Identity, and Nationhood: Karen Mother Tongue Based Education in the Thai–Burmese Border Region,” by Hayso Thako and Tony Waters. Social Sciences. 2023, 12(3), 163;

Hayso Thako has more than 20 years of experience working in Karen education fields and capacity building on the Thai-Myanmar border. Since 2015, he has been a leader in refugee education. He is the head of the Bureau of Higher Education at the Karen Education and Culture Department (KECD), and president of the Institute of Higher Education for KECD and KRC-EE.

Tony Waters is a professor of sociology, currently at Leuphana University, Germany. Previously he taught at Payap University in Chiang Mai, Thailand, and California State University in Chico, the US. He is an occasional contributor to The Irrawaddy. His email is [email protected].