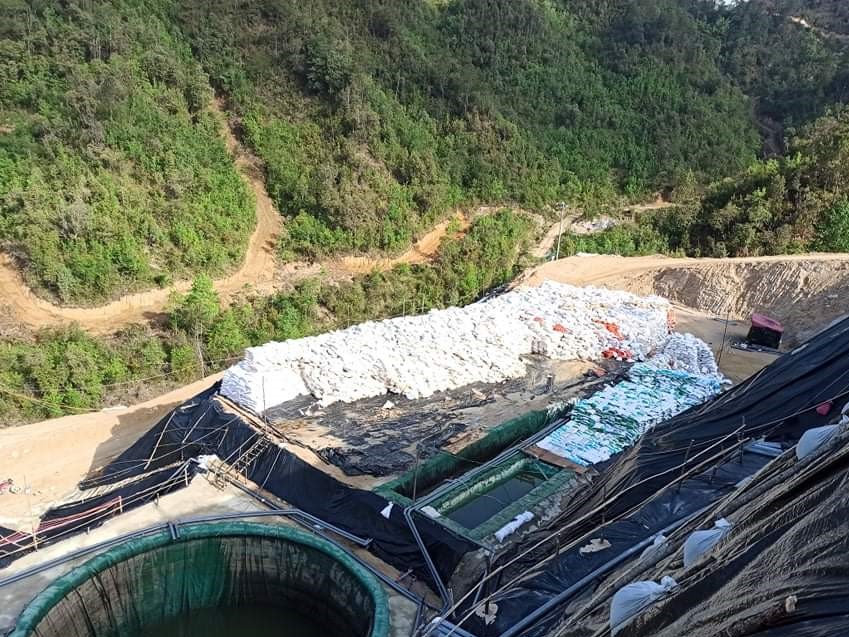

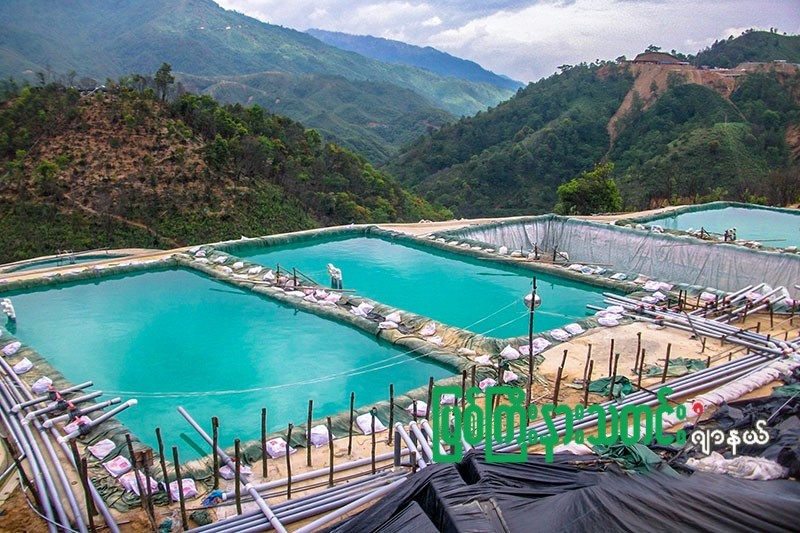

Recent reports by Global Witness and AP news highlight severe environmental destruction by unregulated and illegal rare earths extraction (REE) in northeastern Myanmar bordering China. “There is a name for what Myanmar has become: A “sacrifice zone,” or a place that destroys itself for the good of the world. The sacrifice is visible from the air, in toxic turquoise pools that dot the landscape covered by mountain jungles just a few years ago. “

Global Witness found over 2,700 collection pools at almost 300 separate locations that sprawl across an area comparable to the size of Singapore. REE mining is highly toxic, and its environmental toll has led to the closure of many mines in China in 2016. Since then, the industry has shifted to Myanmar with thousands of Chinese flooding into the country from Ganzhou, Jiangxi Province, known as China’s “rare earth kingdom”.

All the heavy rare earths illegally mined in Myanmar are exported to China, and the export has exponentially increased within a few years, from US$1.5 million in 2014 to $789 million in 2021. In China, five state-owned companies have a monopoly on mining and processing of these heavy rare earths that smart tech products like smartphones, electric vehicles and energy-conserving home electronics rely on. These heavy rare earths finally end up in the supply chains of international companies, including prominent ones such as General Motors, Volkswagen, Mercedes, Tesla and Apple.

One of the conflict zones in Myanmar, a mountainous corner of Kachin known as Special Region 1 has become the world’s largest source of supply for heavy rare earths. Special Region 1 is controlled by ageing warlord Zakhung Tin Ying and his militias affiliated with Myanmar’s brutal military junta. Ironically, increasing global demand for rare earths for clean energy has made those militia and military authorities unimaginably rich at the expense of local ecosystems, livelihoods and access to land, forests and safe drinking water.

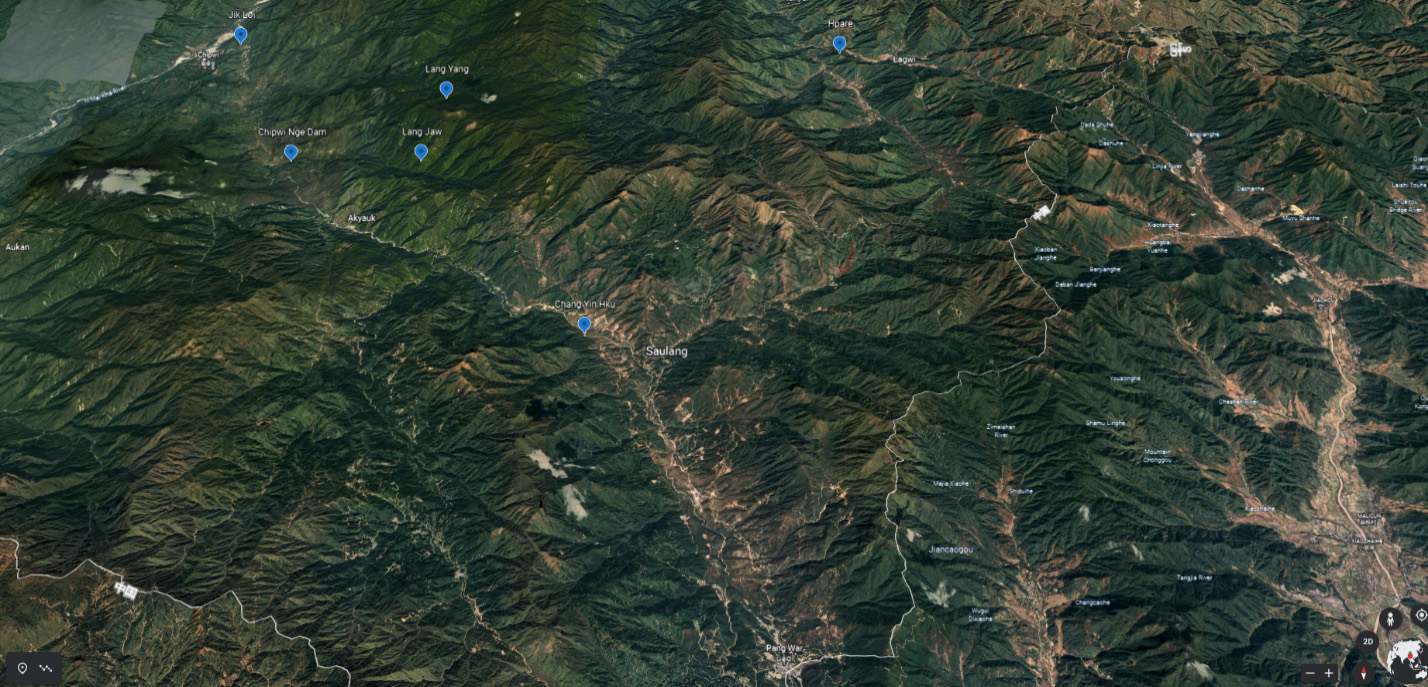

Given the devastating situations of local communities in Special Region 1, we talked to some locals in one part of the region, specifically some villages in Chipwi Township situated between Pang War and Chipwi and surrounding areas in early 2022. It aims to examine how local communities in those villages along the Chipwi Creek and surrounding areas impacted by REE mines have been coping with the situation. We found devastating environmental damages and negative impacts on communities’ livelihoods and their clean water sources. Our analysis of their daily experience reveals that REE has made communities in the area socially fragmented, fragile and extremely vulnerable, with a bleak future for the next generations. The deficit in sovereignty in the region has manifested in the booming illegal rare earths mine industry across the lawless and porous border. The situation has implications for peace, conflict and security on both sides of the border.

Social inequality, fragmentation and fragility in the sacrifice zone

Villages in the study area spread across Chipwi Creek between Pang War and Chipwi and surrounding areas with varying population sizes. Many villages consist of approximately 20 to 50 households, while a few have 80 to 300 households. It is estimated that Chipwi Township’s population is around 20,000 people. Chipwi Township consists of two towns, Chipwi and Pang War, and 118 villages. Our study area includes Pang War and some villages along Chipwi Creek and the surrounding area (see the map). Kachin tribes, namely, Lacid, Ngo Chang, Lisu, Laovoh and a few Jinghpaw reside in the area. Christianity is the predominant religion, with 1 percent practicing Animism. There is at least a church in every village. We found that in some villages, there is more than one church, and in those cases, some discord among churches due to disagreement on the sharing of the profit from REE.

Until the late 1990s, the lifestyle of those villagers was largely agrarian, but it has now significantly changed with the booming rare earths extraction. In fact, Zahkung Tin Ying and his groups have been engaged in various lucrative business deals in the special region, such as logging, bamboo trading, cattle trading, and exploitation of various minerals such as iron, tin, tungsten, marble, lead and zinc since they signed a ceasefire agreement with the military in 1990. They transformed their ceasefire groups to a Border Guard Force (BGF) under the command of the military in 2009. Even before 2010, Tin Ying started rare earth extraction with the backing of the military.

This area controlled by militias and BGFs affiliated with the military exemplifies a gap in economic and social status caused by unequal distribution of wealth and the negative impact of illegal mining. While one-quarter of the population is extremely rich, the rest is faced with a deteriorating economic and social situation. Grievances and social discord in society are widening out of a lack of rule of law and a poor justice system.

Gap in economic and social status

At the top of the social strata are Tin Ying’s family, relatives and allies, including authorities of BGFs and militias. Militia authorities and their allies earn a fortune by renting their land to REE mine sites given that the militia monopolizes these lands and registers them under their name using their authority. In some cases, they might rent their land close to the village without considering its negative impact. In addition, the militia collects various kinds of taxes relating to REE businesses, including informal REE permits to Chinese businessmen, passenger trucks and trucks with loads of REE passing through border gates. They also reinvest in REE mines. According to interviews, estimated investment per site amounts to at least 40 million yuan (about $6 million).

At the secondary level of the social strata are ordinary villagers, militias at lower ranks and their relatives, who have a connection with militia authorities and Chinese businessmen. They also earn a huge profit, but to a lesser extent than militia authorities, by working as agents who either connect Chinese with other villagers to rent village lands, or by looking for general workers to work at REE mine sites or supervising REE mine sites. Agents or brokers manage REE sites on behalf of bosses behind the investment. One rarely knows who the real boss of a particular mine is, which can include Chinese businessmen and militia themselves. Some villagers reinvest their wealth in transport businesses to carry REE loads, and some run commodity shops and restaurants to cater to Chinese migrants and internal migrants from other parts of the country.

At the lowest of the strata are villagers who have no connection with authorities. Some of them work at REE mine sites as laborers. They earn between 1.5 million to 2 million kyats ($700 to $900) by working at REE mine sites. Although they earn much more than a general worker can in any other part of the country, the nature of work includes exposure to chemicals that harm the health of workers themselves and local people.

Some still rely on their crops such as cardamom, walnuts, potatoes, corn, mustard, black peppers, quinces, apples and livestock, such as herd and cattle farms. They now have lost their natural market, nutritious fish from pristine natural streams, forests endowed with traditional herbal medicines and orchids, and good pastures for their cattle to REE mines. Additionally, Chinese do not buy their crops or pay reasonable prices anymore, especially those crops within 80 km of REE mine sites.

Among such villagers are Internally Displaced People (IDPs) in the area. For instance, Jik Loi Village, situated at the bank of Chipwi Creek, about a 6-km distance from Chipwi, was impacted by the 2011-12 civil war between the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and the military. Jik Loi IDPs were staying at Hpare, which is situated about 30 km north of Pang War. When Jik Loi IDPs returned to their village, the bad smell of the Creek forced them to leave their native place again. According to interviews, the whole village had to be reestablished at a new place far away from the Creek. This makes their lives even more difficult because they are unable to access clean water, fish and vegetables from their natural market.

According to the interviews, militia authorities and villagers who got huge profits from REE bought properties like cars and expensive real estate in cities like Myitkyina, Mandalay or Yangon. They have moved to those places while continuing business activities on the border land. Prior to COVID and subsequent Chinese border restrictions, those rich people sent their children to schools in China and bought properties there. On the other hand, many ordinary villagers who remain in their native place are left with toxic land and water with a bleak future.

Our analysis of the daily experience of the communities in the study area reveals various social strata due to uneven wealth distribution and signifies a gap between the rich and the poor and the powerful and the powerless. This has led to social discord and grievances.

Widening social discord and grievances

Fearful of raising their voices against REE mines, locals rarely raise their concerns. The situation has worsened since the coup, with the doors to the civic space being closed, not only at the local level but also at the national level. Powerful and rich militias and their allies, who have benefited from this lucrative business, use various means to shut down concerned voices, including threats, coercion and incentives.

A few years ago, some locals were arrested for raising their voices against REE mines. Recently in April of this year, a local rights defender against REE mine extraction was arrested by the militia, according to Kachin News. A recent report of Global Witness also includes a threat from militia leaders to REE opponents.

Another way of shutting down complaints is giving away a lump sum amount of compensation by Chinese businessmen to those who lost their lives or farmland. Locals said family members of a worker who was killed by a landslide in the REE mine sites or a worker who was crushed to death by a REE-loaded truck, received thousands of yuan as compensation. Thousands of yuan were given in compensation for some farms damaged by soil erosion from REE mines. One of the locals remarked that “They put money [as a] priority, and they solve everything with money. Here money means justice. Villagers have never seen such a huge amount of money in their lives, and they lost their sense of justice and spiritual values.”

One of the locals revealed that nowadays, some villages have no choice. Given the total destruction of the environment, they just rent their village land to REE mines. In one village, villagers agreed to rent a hill near their village to extract REE, and each household reportedly receives 5,000 yuan. In some villages, renting village land for REE and sharing profits among households ends up in disputes. Some complain that they do not receive a fair share when splitting the earnings among themselves and hence, also among the churches they attend. Lack of social cohesion and widening discord and grievances among community members and even among religious entities in the area have manifested in a booming REE industry and money-oriented mindset.

Development left behind, destruction and a bleak future for next generations

Although there are some public services and development activities like free English and Chinese classes in Pang War, the headquarter of Tin Ying’s militia, other villages have no adequate infrastructure, public services and development activities. Many villages still do not have electricity apart from two villages with the support of an individual militia authority and a Chinese investor. Pang War relies on electricity from China and Chipwi on the Chipwi Nge hydropower dam.

According to the locals, there are only four high schools in the whole of Chipwi Township, and the matriculation exam pass rate is less than 10 percent. There is one high school in Pang War. However, in other villages, only during the NLD government era did the government open one primary school per village. Given that the region is semi-autonomous, both the government and the militia controlled the area. However, since the coup, the area has been subjected to absolute control by the militia backed by the military.

Prior to COVID, people in the area mostly depended on China for healthcare. However, COVID hindered them from crossing the border to get medication in China. Those who can afford it nowadays travel to cities like Myitkyina, Mandalay or Yangon for their health-related matters. There are only two public hospitals: one in Pang War and another in Chipwi. During the NLD era, one clinic was open per five villages. There were also public nurses who used to visit villages to raise reproductive health awareness and provide care in every village. One of the locals said, nowadays, such activities have been stalled.

He said “militia authorities are not interested in protecting the environment and developing the region. Instead, they are only thinking of extending REE mines and extracting them as much as possible. Nowadays, mine sites are extended closer to Chipwi.” It is not surprising that militia authorities are now immensely rich and enjoy their wealth in capital cities, either in China or Myanmar. They do not care about local development.

Destruction

With increased REE activities, the environment has been destroyed. REE mines have left the flora and fauna of the area, and many of its pristine water sources, in destruction. A local person lamented, “Within a decade, all lands have been destroyed, and bald hills with perforated metal sheets have been left.” Traveling is challenging, with frequent landslides every 6 to 9 km along the way from Chipwi to Pang War, especially during monsoon. In some villages, roads are no longer in good condition. For instance, Lang Yang, one of the villages between Chipwi and Pang War, has been known as a mining village since long before REE extraction. A company owned by Tin Ying’s son, Zahkung Ying Sau, has been extracting a kind of metal in the village. No one knows the exact kind of metal that has been extracted. The locals said the village’s streets have been destroyed with lots of big holes and muddy paddles. In villages like Chang Ying Hku near Pang War, beautifully paved roads with pine trees along the side have been destroyed due to REE trucks.

A bleak outlook

Nowadays, local youths do odd jobs like working at gambling houses or at logging sites and mining sites near their villages, and others go and work in China. One of the locals said, “Now we earn Chinese yuan, but it will not last long. Within a few years, there will be nothing left. Even now, we can no longer depend on our forests, water and land for farming anymore. I am sure we will have to face difficulties. We won’t survive here if we don’t have money.” He thinks an option for survival for future generation would be turning the area into a trading border area. Otherwise, he said, the area will be a deserted land since our next generations will have to migrate to other places without natural resources to rely on.

It signifies the fact that the booming of the REE industry and increased income of some individuals are not correlated with local development, and a sustainable future, but rather a destruction of its environment and existing infrastructure, due to the illegal and unregulated nature of the industry.

Sovereignty deficit

Chinese yuan is the main currency used in this border area. Given the nature of cross-border tradition, and kinship ties across border areas, the China-Myanmar border is a porous one. Corruption and collusion of militia authorities with the Chinese administration on China’s side enable illegal trading smoothly. One of the locals said that at border gates, 3,000 yuan must be paid for any kind of truck, including trucks loaded with chemicals and equipment for REE extraction and REE loads. But they were not sure how much Chinese custom gates charge them.

The corrupt leaders of the area, the military, China and the rest of the world can maintain a lucrative income from REE. The sacrifice of the area will remain until the resources run out within this current situation in Myanmar with the illegal coup and lawless state. One of the locals lamented that the “Chinese demand all natural resources from here. They don’t care about the destruction of the environment, human resources and villages.”

REE is not the only reason for China’s encroachment. Locals have been troubled by terrible foul and pungent odors from what they call “a color dying factory” that chokes their breath. The factory is on the bank of Chipwi Creek and about 16 km from where REE is burnt between Pangwa and Chang Ying Hku. Locals said they have no idea what the factory is producing. They predict that the number of such factories will increase since local militia officials reportedly earn about 1 million yuan from letting the factory open in the area. According to the locals, the Chinese government does not allow that kind of factory to be set up in China due to waste from the factory affecting the environment, and taxes imposed on this kind of factory are very high in China.

It is likely a textile factory. Some news sources said in China, textile factories have been facing restricted environmental regulations imposed by the Chinese government. Complying with such regulations are costly for the factories. It is also possibly a metal cleaning factory. No locals that we contacted know what kind of factory it is. However, one thing people came to realize is that if secret activities happening on the Myanmar border hurt China’s interests, the government immediately takes action. Otherwise, they keep their lips tight if an enormous amount of profit is involved. If China wanted to, it could intervene. In 2008, “the biggest casino in Chang Ying Hku in the controlled area of NDA-K near Pangwah Pass on the Burma-China border was closed down because about 80 Chinese gamblers were either dead or missing. The pressure to close came from the Chinese government,” said NDA-K sources.

Given the above case, many locals have some doubts about their neighboring country, even when they support Myanmar, questioning whether they are genuine or not with their good will. Some see COVID vaccine donations and testing activities in Pang War and Chipwi as something that does not come from altruism. One remarked, “China supported COVID prevention materials, equipment, even testing machines to prevent COVID from spreading in Pang War. They do not want to postpone REE extraction. It’s all for their own benefit.” The locals said REE was postponed only for a year during COVID. Even during COVID, some Chinese migrants reportedly remained in Myanmar. One of the locals said that Chinese migrants pay bribes at border gates and enter Myanmar freely without restriction, both legally and illegally.

On the other hand, due to the COVID-induced border restrictions, a porous border is no longer easily traversed, especially for ordinary Kachin villagers in the area. One of the locals said China is playing loudspeaker announcement every morning on the border that illegally entering China from Myanmar is not allowed.

It arouses a sense of resentment among local communities. One of the locals said, “In the future, these areas will be overwhelmed by Chinese from China and will become an exporting gate.” Some locals comment that China exploits natural resources from their soil and discriminates against local people. They said Chinese SIM cards that start with “18” are only for Chinese citizens and they have access to premium connections with very low charges, while SIM cards that start with “17” or “15” are for non-Chinese with bad connections and higher charges.

The sovereignty of a country to guard its border against the intrusion of a foreign entity, in this case, specifically in the form of exploiting resources, has been lost due to the illegal and unregulated businesses, including REE in this border area facilitated by corrupted militia and the military authorities.

Implications for peace and security

The exploitative and unregulated situation in the sacrifice zone has implications for peace, conflict and security on both sides of the border. Analysts have already pointed out how REE has provided funding to conflict parties. A recent Global Witness report also highlights that “there is a high risk that revenues from rare earth mining are being used to fund the military’s abuses against civilians, which have intensified since its February 2021 coup. This is nothing new; Myanmar’s military has funded itself for decades by looting the country’s rich natural resources, including the multi-billion-dollar jade, gemstone, and timber industries.”

Since the area is controlled by the militia backed by the military, guns and fighting have been silent since the early 1990s except in 2011 when fighting resumed between KIA and the military and its militias. Since the coup, clashes between those conflict parties have occurred in some parts of Kachin. Armed confrontations between them are likely to be escalated in coming weeks and months.

Given that the KIA controls a few parts of the study area, tension is always there. In the study area, one of the villages where REE is being extracted is a militia-controlled area adjacent to the KIA’s controlled area where REE is not allowed. While some locals have concerns that there might be some renewed conflict between conflict parties in the area, others think the likelihood is low due to China’s influence on those parties and its expectation of them not to jeopardize China’s business interests.

Hpare, about 30 km north of Pang War, was separated after the civil war in 2011 into upper Hpare, controlled by the militia, and lower Hpare, controlled by the KIA. REE has been extracted from all the surrounding hills within 4-6 km of Hpare. All the streams around the village have been polluted by REE waste. Around the village, some farming lands remain, and villagers only do potatoes and corn farming. Only one stream named Hkang Shing that flows through the middle of the village is protected from damages by REE waste under the authority of KIA.

Regardless, in the present time, the imminent security threats incurred by REE are booming gambling and drug issues related to a flood of migrants, both from China and from other parts of Kachin and other parts of Myanmar. In fact, the border area was already being affected by such issues even before REE, and REE just makes it worse. It is estimated that the number of internal migrant workers could range from 4,000 to 5,000 in the area, and Chinese migrants, including businessmen and skilled workers, could number as many as 16,000.

Drug use is booming at REE sites since workers are falsely encouraged to think that drugs will help them by giving them strength to work hard. The booming drug abuse and gambling has caused increased rates of crimes such as theft, robbery and violence.

One of the local miners who worked at a mine site a few years ago said, “All the workers are easily addicted to drugs by working in those sites. I worked at a metal mine last year. They gave us meth freely. If we want heroin or opium or yaba, all drugs can be freely used in mines. They are just assigned day and night. Night workers use almost all kinds of drugs more than day workers.” He continued, “We have to buy drugs by ourselves, especially night workers because the drugs they gave us were not enough anymore. Even if we earned 300 yuan per day, it was not enough since we spent most of our salary on drugs. Working in mines and using drugs is harmful to our health. I had worked there for four months, but I am suffering from lung pleural effusion. That is why the Chinese do not employ workers who have been working for a year.” In Chang Ying Hku, once a beautiful, quiet and green border village near Pang War, people recount how they did not need fences or need to close their doors in the past. But nowadays, they face security threats. They said, “Thieves break into our houses even though we lock the houses. Drugs are booming and syringes and needles are spreading everywhere. Some villagers have been injured by those needles.” Chang Ying Hku was affected by Chinese gambling businesses in the 2000s. Even after the gambling house was shut down in 2008, nowadays, thousands of REE miners, dealers and shop owners have been staying there and entertainments like KTV and massage parlors are booming with an increasing number of commercial sex workers.

One of the locals said “Chinese love gambling. Quarrels or fighting always come up at gambling houses. In one case, two women who worked at a gambling house were killed amidst such quarrels.” In addition to physical threats, economic insecurity has been increasing due to increased commodity prices in the area.

Due to increased demand for accommodation, commodities and food due to migration, commodities and real estate prices have been increasing in the area, and the population from the lowest strata has been hit hard. In fact, high prices in real estate are not only seen in the border area but also in cities like Myitkyina, Mandalay and Yangon. Due to high demand from rich people from those border areas in these cities, real estate prices have been rising for some time. The issue is made worse by the economic mismanagement of the junta since the coup, pushing the grassroots population of the country into desperate poverty and insecurity. It shows how illegal businesses along with illegal migration have increased negative impacts, including booming drug abuse and gambling, and threaten the physical and economic security of the area. It also has implications for other parts of the country.

Conclusion

The social and economic landscape of the sacrifice zone reveals that the impact of illegal business practices and natural resource exploitation in the border area has widespread implications for human security issues, including increased social inequality, fragmentation, vulnerability, and overall, the country’s peace and conflict dynamics. It has also implications for rising anti-China sentiment since the coup. This in-depth analysis shows that the destruction is not only causing environmental and social woes for the people in the region. It is also a sovereignty issue, fueling a loss of trust in the good will of Myanmar’s powerful neighboring country.

Corporate Accountability Myanmar (CAM) is a group of local researchers formed in 2020 to conduct research on corporate accountability issues in Myanmar.