As someone who has reached the third phase of life, “the age of seeking Dhamma,” according to Buddhist custom, I have realized that the world’s other major religions must also have some positive contributions to make to humanity. Based on this idea, I have been studying these other major religions in recent years. On modern media platforms such as YouTube, as well as in recent publications, I have come across several debates and discussions on religion, centering on what it has contributed to human society in positive as well as negative ways. I find many such debates in the Western media are open and frank, contrary to our way — a result of our nation’s British upbringing — that “one should not discuss religion.” Many such debates, as well as academic studies, also address the issues of religious extremism and religious fundamentalism, which have become a serious global security threat, especially to the Western world, over the past 20 years or so, along with other issues that European countries are currently facing as the result of migration crises.

Many of the scholars and religious leaders involved in these debates and discussions offer amicable criticisms and defenses of each side, based on the relevant teachings and scriptures, as well as on the historical deeds and conduct of the followers of the respective religions. They also offer comparisons with other religions, including Buddhism. Concerning Buddhism, most authors and debaters express amicable opinions, as Buddhism has no place for violence or belligerence in its teachings or in the historical accounts that result from or are stimulated by the teachings. On the other hand, during more heated debates, just to show that other religions are capable of spawning religious extremism and terrorist attacks, terms like “Buddhist Extremists,” “Religious Conflicts in Myanmar,” “Karma and the Killings” etc. are used to indicate that we, though in a Buddhist country, are also capable of such behaviors and conduct.

As an academic, I surely have no suggestions regarding the ways and means of solving our dilemma and predicament, which our nation has inherited from the events of 19th and 20th centuries. However, as a Buddhist I certainly have objections to fallacies and mistaken assertions. Simply put, my reasoning is as follows: The problems our country is facing are connected with immigration and legal matters; these are not by any means associated with religion or concerned with Buddhism. I shall support this statement with concrete data.

It is a historical fact that the areas of the Rakhine Kingdom, before it was integrated into the rest of the Burmese Kingdom in 1785, covered the Chittagong District and the Chittagong Hill Tracts, presently in Bangladesh. For this reason, of the approximately 160,000 people who live in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, 48% are Theravada Buddhists according to the 2011 Bangladesh census, including three semi-autonomous regions within Bangladesh: Khagrachari, Rangamati and Bandarban.(1) Of the Buddhist community of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, a large percentage is of the Marma ethnic group, the descendants of the Bago-Hanthawaddy Dynasty of the 16th century. (The details of this history can be studied in the relevant literature.)

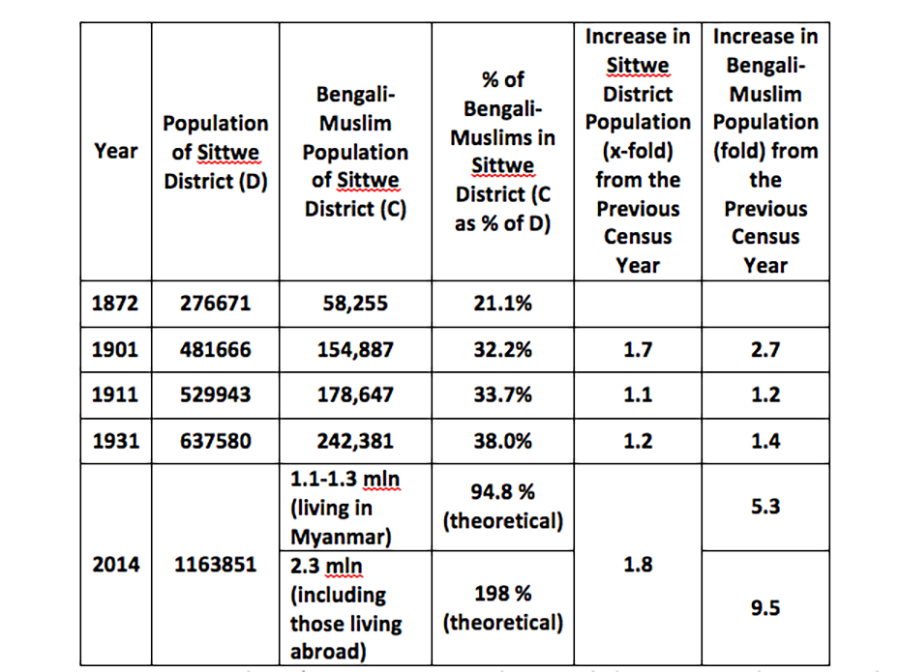

It is also clear that there was a Bengali population on the Myanmar side before both our countries came under British rule. Among them were Hindu, Muslim and Buddhist Bengalis. Rakhine State became the first part of Myanmar to be annexed to the British Empire, after the First Anglo-Burmese War in 1826. Owing to the administration system introduced by the British, reliable demographic data for Rakhine can be found in the 1872 census, according to which the population of Sittwe District was 276,671, of which 58,255 or 21% were Bengali-Muslims. It is a known fact that population movement was practically free all throughout the colonial period. As a matter of fact, this was the case, with a few restrictions, until the 1980s. Due to this essentially free migration, along with different customs and behaviors, the Bengali-Muslim population of Sittwe District increased 2.7 fold to 33.7% of the total Sittwe population by 1901 (versus only a 1.7-fold increase in the overall population of Sittwe District during the same period). It appears that, regrettably, the last reliable data on the Muslim population of Sittwe District is from the 1931 census, in which the Bengali-Muslim population had increased to 38% of the total population of Sittwe. (Data for 1931-2014 is incomplete; see table below.)

According to the latest data from several media sources, in 2014 there were between 1 and 1.3 million Bengali-Muslims in Sittwe District, in addition to around 1 million living abroad; this gives a total so-called Rohingya population of around 2.3 million. (2) This implies that the so-called Rohingya population increased more than nine-fold between 1931 and 2014, whereas the Sittwe District population itself saw a 1.8-fold increase during the same period. Obviously, this discrepancy and inconsistency can only be attributed to immigration from other regions.

Overall population and Bengali-Muslim population growth in Sittwe District

Source: Census data. (Sittwe District population includes nine townships, as in the British colonial period: Sittwe, Ponnagyun, Pauktaw, Yathedaung, Mrauk U, Kyauktaw, Minbwa, Maungdaw and Bothidaung. What is now Taungpyoletwe Sub-township was formerly part of Maungdaw)

Concerning the term “Rohingya”, and the issue of whether they are an indigenous race or not, this term was not known and not used even by Bengali-Muslims themselves until the late 1950s. The British administration was exact and systematic; starting from 1872, the decadal censuses included precise information on race, religion, and indigenous or foreign status. (For example, the Indian population was divided into nine groups, the Chinese into five, etc.) Data was collected in all townships. There was no mention of this race called Rohingya. Another source of information on the indigenous races of Myanmar is the 1931 book “Races of Burma” by Major C.M. Enriquez. (3) He counted and described all the national races of Myanmar, right down to the minute details of their physical stature and appearance, and even the mental characteristics of the national races of Myanmar. The book makes no mention of this race.

Concerning linguistic affiliation, I have dedicated myself considerably to studying the languages and peoples of this region from the time I lived there in the 1980s while working for the United Nations Human Settlements Program (UN-Habitat). One of my assignments was the planning of the Ramu region. (Ramu is an upazila, or sub-region, of Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar District. The Burmese name is Pan Wa — the location of the Battle of Pan Wa during the First Anglo-Burmese War.) The Bengalis in Sittwe District speak a kind of Bengali dialect, the same one that is spoken in Ramu and in Cox’s Bazar. It is a branch of the Chittagong-Bengali dialect, considerably different from the standard Bengali that one hears on Bangladesh’s national radio or television. The dialect is spoken by the Buddhist, Muslim and Hindu Bengalis in these areas. Buddhist Bengalis from these areas usually have family names like Barua; a common surname of Hindu-Bengalis is Chakrabarti; and Muslim-Bengalis normally have Arabic/Islamic names. Regardless of the faith or which side of the border they live on, the Bengali population in these regions all speak the same dialect. Educated people can also speak standard Bengali.

The truth is that this term, Rohingya, was never widely known, or even used by most ordinary Muslim-Bengalis. I have tested this myself several times during my stay in these areas in the 1980s and also later on during my official duties in Rakhine State in the 1990s. When asked, “What is your ethnicity [lu myo]?” they immediately answer “Bengali.” This term “Rohingya” was simply invented by the educated upper class Muslims of this area. Furthermore, it is not logical for any group of people to have such a name, as “Rohin” simply means “Rakhine” in the Bengali language.

The serious animosities in Rakhine started during World War II, in connection with the endeavors to separate Pakistan from India. In the face of the Japanese invasion, the retreating British Army gave weapons to the Bengali-Muslims. In March 1942, there were killings by both sides in northern Rakhine State, in Minbya and Mrauk-U townships.(4) After the war, the Muslim leaders of Rakhine founded the Arakan Muslim League in Sittwe and contacted Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, asking for his assistance in incorporating the Mayu region of Rakhine into Pakistan. The proposal was turned down and never initiated by Jinnah, as that would have been tantamount to interference in the matters of a neighboring country;(5) Jinnah also mentioned this matter to General Aung San during their meeting in 1947, while on his way to England to participate in independence negotiations. (6) Shortly afterwards, some Sittwe Muslims started a rebel organization named “Muja-Hid” prior to Myanmar’s Independence in January 1948. (7) In short, these are the main points that prove that immigration is the main source of the issues and the problems that later on resulted in undertakings to achieve separation.

To rebut the accusations that these are religious conflicts, we should remember that Buddha in his lifetime, as Prince Siddhartha or afterwards as Buddha Gautama, never held a sword or any kind of weapon in his hand. There are several verses in the Sutta Pitika concerning hatred and vengeance, and all his teachings and actions are based on tolerance rather than “fighting back”. Buddha was once on a battlefield where the armies of two states, the Shakyas and the Kolis, were about to start a war over the use of the water in the Rohni River that ran between Kapilayastu and Koli. Buddha engaged himself between the armies and asked the two warring parties to consider and compare the value of water and that of human blood. This convincing argument ended the matter.

The following are a few of Buddha’s teachings concerning war and hatred.

Hatred is never appeased by hatred in this world; by non-hatred alone is hatred appeased. This a law eternal.

Happy indeed we live, friendly amidst the hostile. Amidst hostile men we dwell free from hatred.

Victory begets enmity, the defeated dwell in pain. Happily, the peaceful live, discarding both victory and defeat. (From Dhammapada, Verses 5, 197 and 201, from the text translated by Acharya Buddharakkhita)

Kyaw Lat is an urban planner and has worked for the United Nations Center for Human Settlements, UN-Habitat in Rakhine State.

Notes:

- Chittagong Hill Tracts, from Wikipedia, the free encyclopaedia

- Rohingya people, from Wikipedia, the free encyclopaedia

- Major C.M. Enriquez, “Races of Burma”, Delhi Publishing 1931

- Ibidem no. 2

- Ibidem no. 2

- Bo Gyoke Aung San Ahmat Taya, by Takatho Nay Win

- Tint Swe, Kyor Po Eikalay ko Chikar Lway