Does Myanmar exercise a neutral foreign policy under de facto leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi? Or is the current policy a departure from those of previous governments?

In a recent interview with Nikkei Asian Review, the State Counselor said, “Our country has maintained a very neutral and, in my opinion, a very commonsensical foreign policy ever since we became independent. [Because] we are a small nation, not yet developed, we [were] never at the stage where we were able to call the shots, as it were.”

Some may be intrigued by the idea that Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is maintaining the neutral and independent policy espoused by former dictator General Ne Win and former Prime Minister U Nu. But is that really the case?

Gen. Ne Win was a brutal dictator, but he was also a shrewd politician and military general who witnessed the British colonization of the country, General Aung San’s legacy and the ups and downs of the country during the Cold War.

With Japanese training he fought with Gen. Aung San (Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s father and the national independence hero) to regain independence.

Gen. Ne Win as neutral foreign policy strategist?

When he became head of the government he kept the country out of the conflict in Southeast Asia, refused American aid and joined the Non-Aligned Movement, though he later withdrew the country from it. Under his leadership Myanmar stayed aloof from Asean, which was formed by five anti-communist countries who signed a defense agreement with the West.

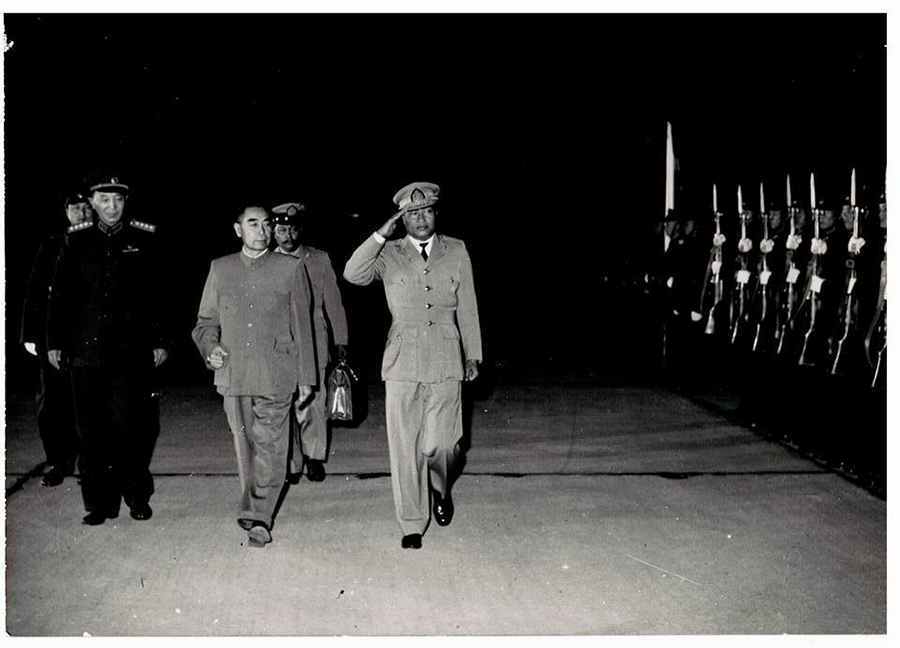

During the Cold War, Gen. Ne Win was known as a “China specialist”, and many Western leaders came to meet him and tap his personal knowledge in order to get a better understanding of communist China under Mao Zedong.

After anti-China riots occurred in Myanmar in 1967, straining relations with Beijing, the general subsequently managed to repair ties with China.

In the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s, even as he was visiting Beijing to meet the Chinese leadership, including Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping, who subsequently became the paramount leader of China, Gen. Ne Win’s subordinates were fighting China-backed communist rebels in Myanmar’s north. The Chinese heavily backed the efforts of Myanmar communist insurgents to topple the Ne Win regime.

While some scholars say Gen. Ne Win exercised a strictly neutral foreign policy, others disagree, pointing out that, for example, he opposed the Soviet Union’s invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968.

But all in all, it is safe to say that Gen. Ne Win managed to keep Myanmar out of conflict in the region.

Gen. Ne Win feared the Americans and the CIA and kept them at arm’s length, while accepting aid from the Soviet Union and China. He was constantly worried about the CIA’s support for Chinese Kuomintang (KMT) nationalists in eastern Shan State, and of the effects of the war in Vietnam.

But, ever careful to preserve his neutralist balancing act, he was prepared to seek military aid from the US and Europe in the face of the serious threat from communist China in the late 1960s.

His subordinates and some Myanmar and foreign scholars praised him for walking a tightrope and maintaining neutrality during the Cold War, balancing his diplomacy between the US, China and the Soviet Union.

NLD’s ‘good neighbor’ policy

Under the National League for Democracy administration, the goal of Myanmar’s foreign policy has been to forge friendly relations with neighboring countries, as well as those further afield. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi once said that “ties between neighbors are always more delicate than those between countries far apart.”

This is true today; we can see how delicate and precarious Myanmar’s foreign relations have become under her leadership, with questions over the country’s sovereignty being raised by China’s growing clout and assertiveness in Myanmar. Enter Japan. How can Tokyo rebalance Myanmar’s dependence on China?

Striking a balance?

In Tokyo, when asked about China’s growing economic influence (the reporter did not ask about political influence) in her country, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi responded, “We see China as a friend, as we see Japan as a friend. And I think it is not right to make people choose between friends.”

Does this mean Daw Aung San Suu Kyi sees the need to strike a balance between powerful countries and economies? Or does she want to demonstrate she is not a puppet of China?

Definitely, she won’t dare upset China. But one must realize that Japan is important in this geopolitical chess game, whatever Daw Aung San Suu Kyi thinks of Japan’s past positions on Myanmar. But still, China is the largest investor in Myanmar, implementing multi-billion-dollar projects, including a deep seaport, new cities, industrial parks, border economic cooperation zones and high-speed railway lines under its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative. Japan, one of the top 10 investors in Myanmar, is still far behind China.

In August, the Japanese and US embassies in Yangon issued a joint statement saying they stand with Myanmar to promote responsible, quality and ethical investment “for the benefit of the people of Myanmar” and “for the country’s economic development”. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi attended a forum organized by the embassies.

When her party came to power, the State Counselor was seen to be betting on China and on peace in the country. Some observers said she was right to visit Beijing first, ahead of the US, after forming a government.

The Global Times, a mouthpiece of the Communist Party of China, published an article a few days after the NLD came to power saying that closer ties with the US at the expense of Chinese strategic interests would not serve Myanmar’s long-term interests. The message to Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and her government was clear: Don’t mess with China.

The press portrayed her as China’s lady. Likewise, the Chinese have bet on Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. The question is, how far will she go to honor China’s business, strategic and national interest in Myanmar and renew Chinese projects suspended under the previous government?

Some have observed that, unlike Gen. Ne Win, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi doesn’t have much time or space in which to develop her foreign policy—if any. Gen. Ne Win enjoyed the backing of the army, but Daw Aung San Suu Kyi doesn’t. She has quickly found foes inside and out. Since the crisis in Rakhine and the West’s subsequent condemnation of Myanmar, the State Counselor has been seen as moving closer to China. She proved wrong those critics who said she would soon be cozying up to the West. She has not.

More importantly, Beijing is watching the State Counselor to see how much she will consent to the West’s influence in Myanmar. Notwithstanding the red carpet welcome and show of friendship between the current government and Beijing, however, one wonders how much Beijing really trusts Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and her Western advisers in Naypyitaw?

Another intriguing question to ponder is whether former President U Thein Sein and his team’s foreign policy was better than the current administration’s policy? The foreign policy of U Thein Sein differed from the previous regime’s, in that he sought to re-engage the West, re-enter the international community and shed the country’s pariah status for good.

China learned a big lesson from the U Thein Sein government, which suspended the controversial Chinese hydropower project in Myitsone, sending a cue to Western governments to lift sanctions.

Who shapes foreign policy?

But then, who really shapes and influences Myanmar’s foreign policy?

Domestically, it is the military. Before Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s visit to Tokyo, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, the commander of Myanmar’s military, flew to Japan, where he met with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and several dignitaries. This shows that Myanmar’s army continues to maintain and engage foreign governments and leaders in order to continue influencing foreign policy. Sen-Gen Min Aung Hlaing has been to several countries including China, India, Russia and Thailand—key nations that are important to Myanmar. He never shies away from discussing security and domestic issues, and he still wields an influence on his counterparts.

Indeed, today Myanmar exercises a neutral foreign policy, but definitely not from strength—rather the opposite. This is dangerous.

While Myanmar exercises a neutral and independent policy, how many times have powerful countries and neighbors interfered in Myanmar’s affairs over the past few decades?

Last but not least, Myanmar and China have agreed to abide by the five principles of peaceful coexistence in international relations: Mutual respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty; mutual non-aggression; mutual non-interference in each other’s internal affairs; equality and mutual benefit; and peaceful co-existence.

But today, who breaks this so-called “peaceful co-existence” when we talk about territorial integrity and sovereignty?

The recent attack by ethnic armed groups on a defense academy in Pyin Oo Lwin, Mandalay Region, was a wake-up call to many, as rebels and warlords who are considered to be proxies of the Chinese were involved. The message is that they can make not only peace, but also war—and do damage to the economy. What does this incident tell us about China’s influence on the internal affairs of Myanmar and the fragile peace process?

Myanmar is a weak state, and since the 1950s the policy of neutral and independent foreign policy has been maintained; no one has made a drastic turn away from the policy, even under Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

Well, that’s it. As the State Counselor said, “We’ve always maintained that our foreign policy will be vibrant and independent, and based on friendship towards all nations. So we welcome all friends who are happy to cooperate with us. And we would not like our country to become a bone of contention for any other group of countries.”

Some say this foreign policy is not a break from the past—more a case of fine-tuning. The answer is to keep walking the tightrope.

You may also like these stories:

The State Counselor Keeps Her Former Enemies Close

Myitsone Dam Is Now a Sovereignty Issue

Look East Policy Is Fine, but a Balancing Act Is Needed