With President Xi Jinping of China arriving in Myanmar’s capital today, it seems an appropriate time to ask whether the much-used phrase “pauk-phaw”, meaning fraternal, is really an accurate description of the relationship between the two neighbors.

Yesterday, a day prior to his two-day trip to mark the 70th anniversary of China-Myanmar diplomatic relations, Xi wrote an article in Myanmar’s state-run newspaper under the title “Writing a New Chapter in Our Millennia-Old Pauk-Phaw Friendship.”

“In Myanmar language, ‘pauk-phaw’ means siblings from the same mother,” Xi wrote. “It is an apt description of the fraternal sentiments between our two peoples, whose close ties date back to ancient times.”

Actually, the president knows that’s not the case, but he uses the term because it is expected of every leader from Myanmar and China on such occasions. In fact, it is nothing more than a cliché that diplomats reach for when they wish to refer to the relationship between the two countries, their peoples and leaders.

In truth, the peoples of Myanmar and China are under no illusions that such a relationship exists. Neither are the two governments. No one feels they are siblings. The countries are close geopolitically, but distant in many ways.

The term “pauk-phaw” implies a close connection, but relations between the two countries and peoples are neither close nor cozy. Coined in the 1950s, the phrase has never acquired any real meaning in Myanmar; it’s hollow jargon whose use is confined to state visits and official messages.

Since 1948, the leaders of Myanmar’s various governments have all been well aware of this, from elected Prime Minister U Nu to the dictator General Ne Win to his successors in the military junta, to Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy government.

Since independence, Myanmar’s foreign policy has been aimed at preventing its giant neighbor from interfering in its internal matters and influencing its governments. Over the years, China has variously lent its support to Myanmar communists, pro-communist groups, and leftist political parties, and ethnic armed groups along the border and even inside the country.

It must seem strange to some foreign countries to see the statements released by several ethnic armed groups based on the China-Myanmar border, including the United Wa State Army, the Kachin Independence Organization, the Mong La’s National Democratic Alliance Army and the Arakan Army, welcoming Xi to Myanmar.

A week before Xi’s visit, the Chinese special envoy for Asian affairs, Sun Guoxiang, separately met with leaders of those groups along the border.

Obviously, China’s influence over the ethnic rebels is a political card it can play. This is nothing new. China has played this game since Ne Win’s era. His socialist regime was quite upset with China’s policy of supporting the Communist Party of Burma, which fought against the Myanmar military from 1948 till 1989.

At the same time, consecutive Myanmar governments have tried to maintain a neutral or non-antagonistic policy toward China. And while some Myanmar governments were very close to Beijing, the country has for the most part managed not to be overly influenced by China. For his part, Ne Win always tried to maintain normal diplomatic relations with Beijing.

Myanmar’s military regime needed China more than previous governments, not because its leaders felt that their Chinese counterparts were their siblings, but because the generals were desperate for China’s help. They had been abandoned politically and economically by the international community, especially the West, due to their gross human rights violations after the 1988 pro-democracy uprising.

China has not been able to impress or win the hearts of the Myanmar people, and has not been able to shake its unethical and immoral image. This stems from a range of actions by China, from its greedy and exploitative business activities in the country to its strong support for the previous military junta, which oppressed Myanmar’s entire population after the 1988 pro-democracy uprising, to its aggressive push to take over new and old business concessions all over the country.

However, regardless of the nature of the “friendship”, in a practical sense the two countries need each other.

Xi’s first trip as president, which comes at the invitation of Myanmar’s President, is very important for the two countries, perhaps more important than that of any other state leader. He will meet President U Win Myint and State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi during his two-day trip to Naypyitaw.

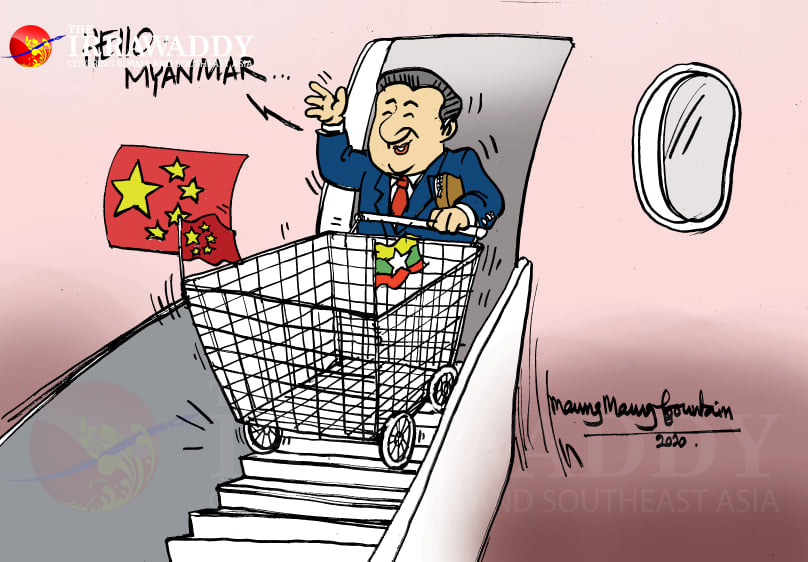

However, the general impression of the visit among Myanmar people was summed up quite neatly in a cartoon published by The Irrawaddy recently. It depicts Xi alighting from his airplane with a big shopping cart (see the cartoon below). That’s how most Myanmar people perceive China— more than other countries, it is seen as constantly trying to exploit the relationship for its own benefit.

Based on his article, the items at the top of Xi’s shopping list during his two-day visit to Myanmar seem to be: 1) the Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone; 2) the China-Myanmar Border Economic Cooperation Zone; and 3) the New Yangon City project.

Among others, the Chinese president underscored these three projects as the main pillars of the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), which is part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Interestingly—or cleverly—he didn’t mention a word about the Myitsone Dam project, which is a controversial and emotional issue to Myanmar people throughout the country, from northern Kachin State to the deep south.

On Wednesday, two days before Xi’s arrival, nearly 40 civil society groups urged the Chinese president to permanently terminate the suspended project, saying it threatens the prosperity of the Myanmar people and that friendly relations between the two countries will deteriorate if the project goes ahead.

Both Xi and his counterparts in Myanmar are well aware of this dam issue. The best option is to terminate it. That might be why he prioritized the three projects mentioned in his article. Those three seem more important when it comes to China’s ambitious BRI-related projects in Myanmar.

Another reason China needs Myanmar is its neighbor’s geopolitically strategic location, which could allow Beijing to extend its presence all the way to the Indian Ocean. With projects on Myanmar’s western coast giving it access to the blue water shipping lanes of the Bay of Bengal and acting as the terminus of a pipeline across the country from Kunming, China would no longer need to rely on the congested Strait of Malacca to import oil and gas from the Gulf.

Perhaps, in terms of diplomacy, it doesn’t matter how far apart Myanmar and China’s leaders are ideologically.

In his article, Xi writes, “China supports the efforts of the Myanmar government to promote peace and reconciliation, and supports Myanmar in safeguarding its legitimate rights and interests and national dignity in the international arena.”

The incumbent elected government led by de facto leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi needs China too. Regarding the peace process and Beijing’s dealings with the ethnic groups on the border, the Myanmar government could be forgiven for being less than fully confident in China. It is believed that China has discouraged the groups from signing the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement, which the Myanmar government has been pushing for several years.

But “in safeguarding its legitimate rights and interests and national dignity in the international arena” as Xi said, the NLD government politically needs China, just as most Myanmar governments in the past have. Simply speaking, it needs China to stand on its side when it faces pressure from the West.

In that case, China is “pauk-phaw” for Myanmar leaders, too. In this matter, however, the approaches and intentions applied by the previous military regimes and the elected government will be different, though they are all aimed at restoring normal diplomatic ties in the broader sense. For instance, Xi shouldn’t expect the opaque and murky business concessions that China received under the previous regime, like the Myitsone Dam project.

Many observers say that these days Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s government is being very cautious in regard to China’s projects in Myanmar, most of which are the result of the previous regime’s opaque concessions to China. The current government has been quite slow and hesitant in approving them, and it’s reported that Xi and his government are losing patience.

But like it or not, Myanmar people will see more Chinese tourists, Chinese projects, Chinese companies, Chinese products and Chinese diplomats across the country. How to regulate them is the responsibility of everyone—not only the government, but all concerned groups and people.

Myanmar governments—of all types—will always do what it takes to survive politically and economically among its giant neighbors, especially China, and the West. But it doesn’t mean that the country will become a “colony” of China. Meanwhile, it doesn’t want to be seen as a “colony” of the West either.

Politically and principally, however, I am pretty sure that the incumbent government, like most people in the country, wants to be close to the West and—unlike China—shares its values, including democracy.

But between China and the West, during Myanmar’s fragile and turbulent transition, the NLD government will be pragmatic as ever in order to maintain a neutral foreign policy—something that will set it apart from its neighboring countries in Southeast Asia.

The “pauk-phaw” relationship doesn’t exist beyond political jargon. What is real is the two countries’ mutual dependence on each other.

You may also like these stories:

Infographics: Chinese Leaders’ Visits to Myanmar Over 6 Decades

Six BRI Projects in Myanmar to Monitor During Chinese President Xi’s Trip

Myanmar, China to Sign Agreements on SEZ, Border Economic Cooperation During President Xi’s Visit