As we read news of Mandalay’s ambition to become a “smart city” with the former royal city in the midst of a high-tech makeover and recently rewarded for its efforts, being named among the top five urban areas in Southeast Asia making progress toward smart-city status. But it still has a long way to go.

To keep our beloved royal city alive, I would prefer to see Mandalay—its charm, rich heritage, historic buildings, palace and temples—preserved as a cultural city, as well as a preservation of its unique pace of life—not too fast and not too slow. The question now is can we save Mandalay?

The country’s last royal capital, at more than 160 years old, is rapidly changing and facing a growing Chinese influence with businesses and unchecked migration flowing in through our northern border.

With Chinese influence growing day by day, perhaps it is time for Mandalay’s chief minister and officials to work hard on preserving the real essence of Mandalay before it is too late.

It is no longer news that Mandalay is becoming a Chinese city. Mandalay life has been obviously impacted by a rapid pace of growth of Chinese businesses, and the ensuing Chinese temples, architecture and restaurants are nestling up to Chinese-financed shopping centers.

There is concern among Mandalay residents about the city’s old heritage and charm being wiped out by greed and ugly modern buildings which have mushroomed over the decades without strict monitoring by officials.

Meanwhile, the Chinese celebrate lavish weddings and parties in expensive hotels and continue to buy up expensive land in prime areas in downtown Mandalay. In fact, the streets outside the old palace are now prime business zones. I see many local Mandalay citizens sit in teashops puffing cheroots, chewing beetle nut and sipping tea: they are slow, while newcomers to Mandalay are moving fast.

Mandalay was founded in 1858 by King Mindon, a devout Buddhist who organized the Fifth Great Buddhist Synod in what was then a relatively new city. Even today, the city remains known as the country’s center of culture and Buddhist learning, and its place in history as the country’s last royal capital makes it a primary symbol of Myanmar sovereignty and identity.

King Mindon is remembered not only as a great king but also as a reformer who envisioned a modernizing country catching up with the rest of the changing world in the 19th century and he tolerated other faiths including Christianity and Islam. But his kingdom was too weak to defend itself against the British colonialists.

When he built the city, some 13 kilometers away from the Irrawaddy River, the lower part of the country was already under the British. The king was concerned about invasion and the range of hostile cannon fire from British ships on the river when he moved the city from Amarapura.

Mindon died in 1878 and was succeeded by his son Thibaw, the last monarch. The British overthrew Thibaw in the Third Anglo-Myanmar War in 1885, and the king and queen were sent to India where he died in exile.

Walking into the palace today, those interested in learning about the history can see some information boards, but they are not enough to grasp the attention of young people who are visiting only to take selfies and have a laugh. The military still occupies much of the land inside the palace walls. The palace belongs to the public and people of Myanmar.

But where is the history? There are many stories recounting how the British took over the palace. They turned it into a headquarters for their occupying forces and demolished buildings. Then lootings began. It signaled the loss of independence and sovereignty of the kingdom. The history that follows has been distorted under the proceeding generals. Our young generations, as well as visitors, deserve to learn the history of these places in Mandalay.

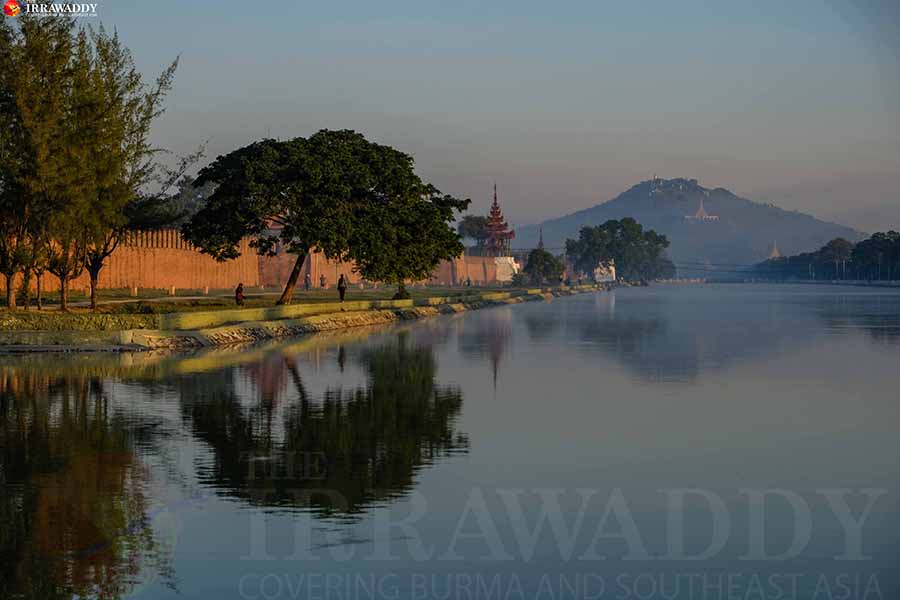

The beautiful moat surrounding the palace walls was rebuilt under the previous regime. It had been destroyed during World War II when occupied by the Japanese and allied forces pounded the city, flattening the palace and destroying several other historic buildings. In the 1990s, as part of their campaign to beautify the country, the notorious generals ordered prisoners to rebuild the moat in an effort to attract tourists. Today, Mandalay will need a stronger effort to rebuild these monuments to remind the people and new generations, as well as to attract tourists and tell the history of the royal city—it is important.

Mandalay is also home to some historical masterpieces of architecture built as monasteries. While in town, visitors should go to the magnificent Shwe Kyaung, Shwe Inn Pin, Kin Wun Mingyi and Yaw Min Gyi monasteries. Both Kin Wun Mingyi and Yaw Min Gyi were royal officials of their time who built magnificent monasteries which today stand wearily waiting to be renovated. One will see fine wood carvings at Shwe Kyaung Monastery which failed to achieve UNESCO’s World Heritage listing when its application was submitted in 1996. Restoration work at the monastery is still underway amid widely shared rumors of the siphoning of restoration funds. Kuthodaw Pagoda, where you can find what’s known as the “world’s largest book,” is worth a visit too, but apart from Shwe Kyaung Monastery, visitors will find very little information on display at any of these locations.

I am told that some teak monasteries and buildings are preserved by respected local abbots. They have saved money and received local donations for the preservation of the finely carved wooden doors, windows and buildings which were built in the 19th century. A shared fear among monks and residents is that if these buildings are handed over to the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture their maintenance will be compromised.

One also wonders at the potential of renovating Gaw Wein Jetty where the country’s last king and queen departed by steamer ship to India, and of providing information of the historical events to students and tourists. A ship, statues and a display of information recounting the whole episode would be educational and attract visitors.

If you are in Amarapura we will see the stunning U Bein Bridge and Mahagandayon Monastery where young monks can be seen walking under the beautiful old trees to receive alms. This old tradition of offering alms to monks is well preserved and quietly observed. It is a peaceful atmosphere, but the question is, how long will it last?

In September, Myanmar and China agreed to establish the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) and the estimated 1,700-kilometer-long corridor will connect Kunming, the capital of China’s Yunnan Province, to Myanmar’s major economic checkpoints—first to Mandalay, and then south-east to Yangon and west to the Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone (SEZ). China is a key supportive neighbor in backing up Myanmar when it faces Western criticism over conflict in northern Rakhine State. There has been criticism that the Myanmar government is increasingly becoming pro-China—just like the previous regime—but there are those who defend the government, asking “Do they have a choice? The west is pushing Myanmar into China’s orbit.”

In any case, the 15-point MoU signed between Myanmar and China stipulates that the two governments agree to collaborate on many sectors including basic infrastructure, construction, manufacturing, agriculture, transport, finance, human resource development, telecommunications, research and technology. I still haven’t found any think tank group in Mandalay researching or studying China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

As night falls and we are watching the sunset by the Irrawaddy River, we dive into discussions with Mandalay friends and one suggests that instead of fearing China, Myanmar must take advantage of its unique geopolitical position to forge stronger economic ties. But how do we strike a balance? Another retorted, questioning what sort of power, capacity, vision and imagination do we have? These debates are endless.

Amid rumors that Chinese President Xi Jinping will visit Myanmar in the near future, residents in Mandalay go about their daily lives. A handful of intellectuals and writers, however, whisper to me that they worry about China’s growing clout in the north and the danger of Myanmar again being a pawn between bullying superpowers. We now see the rise of China and how its economic power has a huge impact on the border regions and is coming deeper inside Myanmar. Mandalay is on its list. “We are falling into China’s hands,” one member of a prominent intellectual family in Mandalay told me.

Our ancestors saw their king and queen taken away, foreign troops fighting over the royal city out of strategic and geopolitical interest and then the destruction of Mandalay. Who knows if in 50 to 100 years the country’s map may ultimately change? Saving Mandalay is not going to be easy.

Aung Zaw is the founding editor-in-chief of The Irrawaddy.