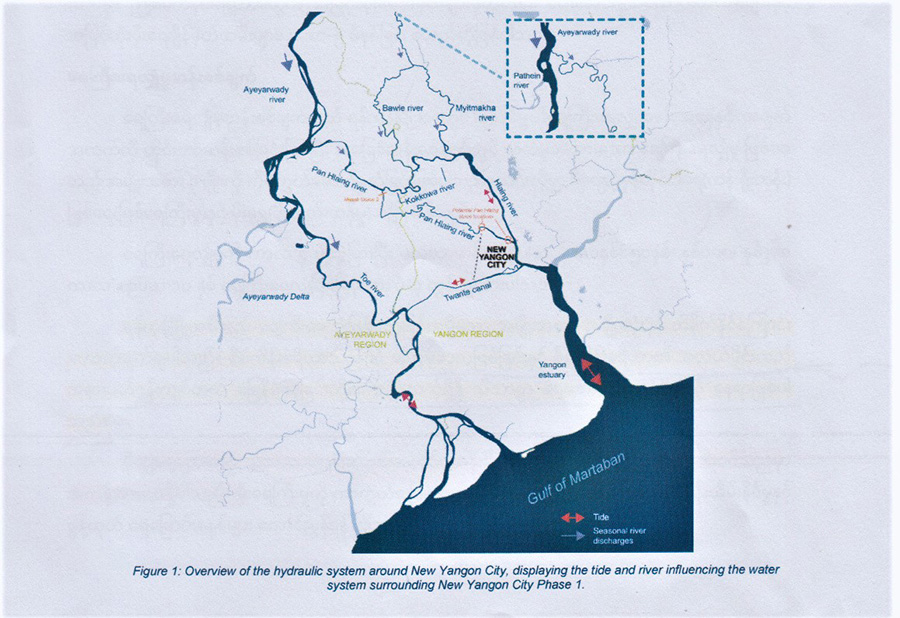

YANGON—Lying less than 5 meters above mean sea level, receiving a large amount of rainfall during the monsoon season and surrounded by waterways on three sides, the nearly 20,000-acres of land on the west bank of the Yangon River that lie directly across from Myanmar’s commercial capital were, until recently, never high on city planners’ list of prime locations for urban development. In fact the area is something of a planner’s nightmare, especially as the water level is prone to increases due to a combination of tidal and storm surges, river discharge and rainfall, posing a significant flood risk to the area.

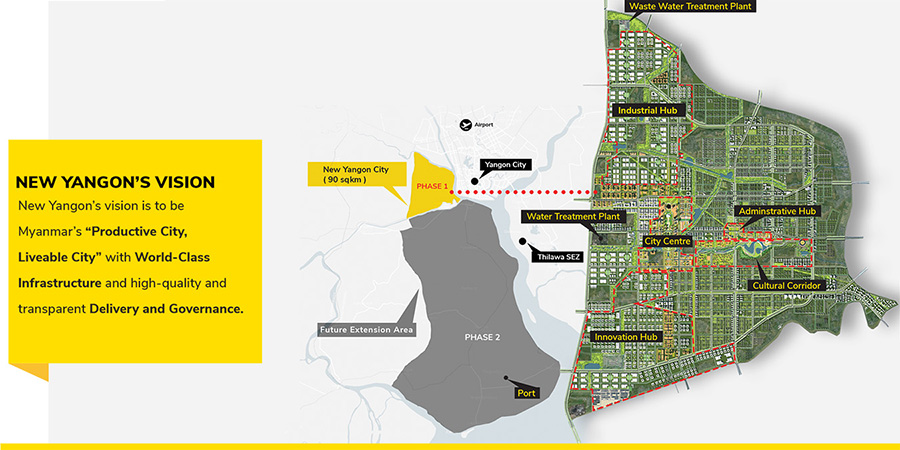

However, this is the exact location for the New Yangon City development—Yangon Chief Minister U Phyo Min Thein’s ambitious plan to transform the less developed and low-lying western bank of the river into a “Smart City”, which he says will create 2 million jobs.

To make it happen, he formed the New Yangon Development Company (NYDC) last year as the sole developer of the project, announcing that it would be fully owned by the government. So far, the project is still in the planning phase. Since its formation, the company has carried out several assessments, including a study of the flood risk to the area.

NYDC released an executive summary, “Strategic Flood Risk Assessment New Yangon City Phase 1”, last month. Undertaken by Royal HaskoningDHV, the assessment advises building a US$100-million (152.66-billion-kyat) “primary ring-dyke system” around the waterfront areas of the site—which is surrounded by the Yangon and Pan Hlaing Rivers as well as the Twante Canal—as the area slated to house New Yangon City is vulnerable to flooding from three sources: tidal and storm surges, river discharge, and rainfall. Without protection, it values the annual economic risk posed to the project by flooding at US$1.2 billion at the current sea level, rising to US$2.1 billion in the event of a 90-cm rise in sea level.

“A significant flood hazard is currently present at the project area, mainly due to the low-lying ground elevations, and the fact that the central part of the project area is lower than its perimeter,” the assessment states.

It adds that “the investment would be more than 300 times smaller than the long-term risk reduction it would create, leading to the conclusion that investing in flood protection up-front is cost-effective and justifiable.”

For all Royal HaskoningDHV’s assurances, questions are now being raised, such as who will foot the US$100-million bill for the construction of the ring dyke. Most importantly, lawmakers and urban experts wonder aloud whether the government and NYDC’s planned flood management system will be properly integrated into the region, fearing surrounding areas will pay the price if floodwaters are diverted by New Yangon City’s protection system into neighboring areas.

“Obviously, if you block its path, water will find another direction to flow in,” said Dr. Kyaw Lat, an urban planner, highlighting the very real risk that nearby areas will be inundated in the absence of a regional flood-management system.

Another urban planning expert, U Than Moe, questioned whether the Yangon government or NYDC have any prevention plan, saying water levels in Yangon and Pan Hlaing are likely to rise if floodwaters from New Yangon City empty into the rivers. As a consequence, he said, Pazundaung Creek, which passes through populated areas of Yangon, and the Bago River will see a rise in their water levels, as the two waterways flow into the Yangon River.

“You can’t just consider the safety of New Yangon City. You also have to think about the repercussions for Yangon,” he said, adding that the project’s surrounding areas like Hlaing Thaya, an urban sprawl just across the Pan Hlaing River, and Kyimyindaing on the eastern bank of the Yangon River, are vulnerable to flooding as well.

It’s not only urban planners who are concerned about New Yangon City’s impact on the regional environment. Royal HaskoningDHV’s summary recommends an integrated regional approach to flood management and flood risk assessment.

Who will pay?

In addition to the concerns over regional flood management, another looming question is who will pay for the US$100-million primary ring dyke recommended by Royal HaskoningDHV to prevent flooding within New Yangon City itself.

From the outset, the project’s sole developer, NYDC, has said it will not contribute to the project’s financing, but will invite investors to participate. The company announced it had secured an initial investment of nearly US$7 million, most of which has gone toward office expenses and assessment fees, according to the auditor general’s report on the Yangon government’s budget for fiscal 2016-17.

The company has signed a framework agreement with corruption-tainted China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) to build six infrastructure projects worth a total of more than US$1.5 billion. The projects’ components include five village townships, two bridges, power plants, water and wastewater treatment plants and an industrial estate. Neither the “primary ring dyke” suggested by the Dutch company, nor any other flood-mitigation infrastructure is anywhere to be seen among the projects announced as part of the agreement. NYDC has not released any details of how the project’s flood-control system would be funded, despite the fact that the final masterplan by AECOM for Phase 1 highlights the need for proper flood control, as “more than 99 percent of the project area is below 5 meters from mean sea level.” AECOM Singapore Pte Ltd was appointed by NYDC to prepare the Master Plan and Strategic Plan for the New Yangon City project in September 2018.

Apart from the ring dyke, the Strategic Flood Risk Assessment summary report also says that drainage into adjacent rivers and canals is impacted by the semi-diurnal tides that prevent gravity flow twice a day. Also, the storage depth may be limited due to the low ground elevation, flat project area and relatively high ground water tables. Large retention volumes would therefore need large surface area, it says.

“A detailed drainage study is recommended to identify the most appropriate drainage infrastructure, to define its dimensions (of e.g. flood gates, water control structures, canals and pumps),” it says. But the report doesn’t state whether the cost of the drainage infrastructure is included in the aforementioned US$100-million flood mitigation measures, like the ring dyke.

Vicky Bowman, director of the Yangon-based Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business, said all the costs—economic, environmental and social—need to be fully taken into account before embarking on such a development project, and the sources of funding clearly identified.

According to Bowman, the details that need to be considered include “the overall cost and feasibility of the necessary flood-prevention and ground build-up measures, the impact this would have on the depth of foundations, as well as the flooding impacts on surrounding areas, and the impacts from which soil would be taken to build up the land.”

Yangon Parliament lawmakers Daw Sandar Min and U Kyaw Zay Ya also wondered who would cover the US$100-million cost of the flood-mitigation measures and who would take responsibility for the possible impacts of the project on Yangon.

“Who will cover the cost? Who will be responsible if something bad happens in surrounding areas? These issues should all be subject to parliamentary scrutiny,” Daw Sandar Min said.

In fact, the New Yangon City project has never been popular among regional lawmakers, who believe the Yangon regional government abused its power in launching the project, failing to use the proper parliamentary channels.

In October last year, when the auditor general’s report was discussed, the regional parliament found that the Yangon government had transferred US$6.5 million from the government budget to NYDC as an initial investment without the parliament’s knowledge. Daw Sandar Min accused the government of abusing its power.

Furthermore, both Daw Sandar Min and U Kyaw Zay Ya complained that the Yangon regional government is implementing the New Yangon City project without consulting parliament.

However, Chief Minister U Phyo Min Thein insisted during the project’s final masterplan consultation in February this year that the development doesn’t need regional approval as it was greenlighted by the Union Parliament under the previous U Thein Sein administration.

But lawmakers point out that the model for the project had changed since it received approval, as the Yangon government formed NYDC as the sole developer, while the old model called for a consortium of three private companies. (The Yangon government canceled the contract between the previous government and the consortium with the companies’ agreement in April 2017 when U Phyo Min Thein told them such a huge project should be run by the government, according to the record of a Q&A session with the chief minister during the final masterplan consultation.)

“It needs to be discussed in the parliament again, as a Chinese company [CCCC] is now involved. The previous model didn’t use a single dime from the government budget, but this one does,” said U Kyaw Zay Ya, referring to NYDC’s 10-billion-kyat initial investment.

For all the questions surrounding the flood-mitigation measures, the NYDC told The Irrawaddy on Tuesday that US$100 million is the estimated investment cost for all primary flood-risk reduction measures, including the primary ring dyke system.

“The funding will come from investment partnerships,” Daw Aye Aye Khine, NYDC’s head of city planning and development, wrote in an email.

Regarding regional flood risk, she said Royal HaskoningDHV’s report recommends that a regional flood study be undertaken by the authorities responsible for regional flood control.

“NYDC is working closely with the government’s Irrigation and Water Utilization Management Department (IWUMD) and Directorate of Water Resources and Improvement of River Systems (DWIR) on various ongoing projects in surrounding areas regarding regional flood risk and water security,” she wrote.

This story was edited on Sept. 19, 2019 to correct the project site’s elevation.