When artillery struck a school in Kha Mwe Chaung Village in Buthidaung Township, northern Rakhine State last Thursday injuring 21 primary students aged between 5 and 10 years, both the Myanmar Military (or Tatmadaw) and the Arakan Army (AA), who are currently fighting each other in the area, denied responsibility.

Instead, they blamed each other.

On that day, Tatmadaw and AA troops clashed some 1 to 3 miles (1.5 to 4.5 kilometers) from the village, according to both sides.

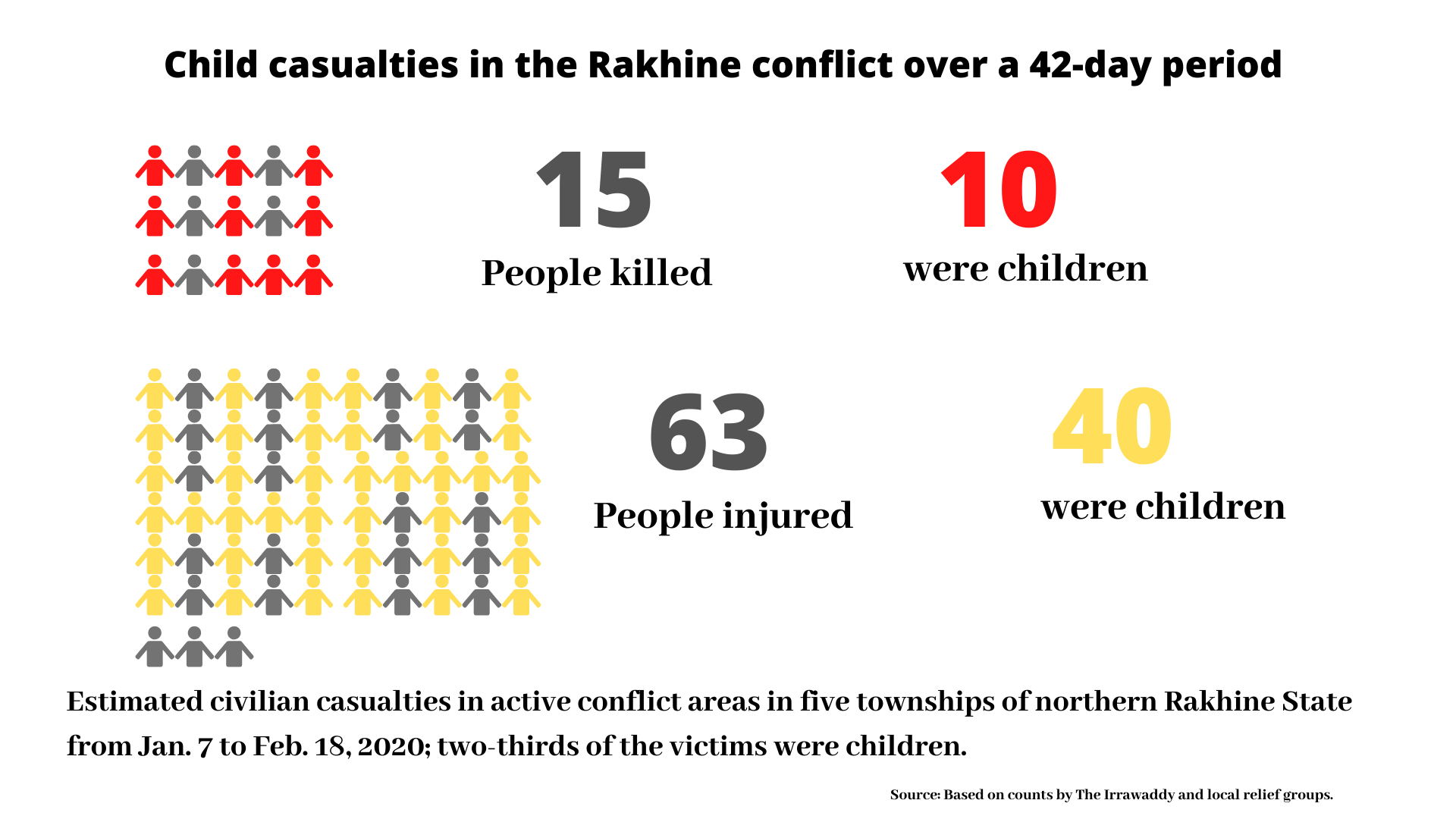

In Rakhine State’s Rathedaung, Buthidaung, Myebon, Mrauk-U and Kyauktaw townships, where the fighting has intensified recently, an estimated 15 people have been killed and 63 injured in the first seven weeks of 2020.

According to the Irrawaddy’s count, about two-thirds of them died from shrapnel wounds after artillery struck their homes, while others died from mine explosions or gunfire from Myanmar military ground troops.

About two-thirds of the casualties, including both dead or injured, were children.

The Feb. 13 incident occurred at the post-primary school at 10 a.m. One girl was severely injured and taken for treatment to Sittwe Hospital. On the same day, children in other parts of Myanmar were celebrating Myanmar Children’s Day, which commemorates the birthday of Myanmar independence hero General Aung San.

Rakhine State parliament Speaker U San Kyaw Hla said in his closing remarks to an emergency session of the legislature on Monday that, “It was very sad actually to hear about it. Should I say it was a sad coincidence that an artillery shell fell on a primary school and hit them on Children’s Day?”

“What’s worse, no perpetrator has been identified for the action,” he said.

The incident sparked anger, sadness and frustration among the Myanmar public.

The speaker added, “The actors in armed exchanges cannot shoot at whatever they want. You should neither take the people nor religious and cultural buildings as your cover.”

He was referring to the armed engagements in Mrauk-U, the ancient capital of the historic Arakanese Kingdom, last year between the Tatmadaw and AA, as well as the stationing of military troops in the compounds of monasteries and hillside pagodas, and the reckless firing of artillery into villages.

The fighting between the AA and the military began in western Myanmar in March 2015, in lesser-known areas of Paletwa Township in Chin State. It intensified in November 2018, causing civilians in the eight townships of northern Rakhine State and Paletwa to flee their homes in fear for their safety.

More than 106,000 locals had been displaced as of Jan. 25, with limited access to food and shelter, according to figures compiled by the Rakhine Ethnic Congress (REC) based in Sittwe. The locals frequently risk their lives, running the risk of being shot at when they try to transport food or simply venture out to rivers or into the woods to look for food.

According to local relief groups and parliamentarians, more than 110 deaths and some 200 injuries have been reported since January 2019, but getting an exact number of casualties is hard. Some go undocumented, given the restrictions on movement in the area.

The speaker added that despite the state parliament repeatedly urging the government to ensure the protection of civilians and maintain historically important buildings, “the government does not pay attention to us.” Thus, he asked whether “our country’s democracy is fading.”

“The civilians are suffering as a result of the exchanges of fire between the military and the AA, but no one takes accountability. What’s more disturbing is that the government, which has the key responsibility to protect civilians, is failing to perform its duty,” the speaker told The Irrawaddy.

Echoing his comments, Rakhine State parliamentarian U Tin Maung Win, who represents Rathedaung constituency, told The Irrawaddy on Wednesday that the government had ignored the state legislature’s calls, and had not even started an investigation into civilian casualties, including the latest school shelling, as it suggested.

Every time an artillery shell strikes a civilian community, he added, locals gather pieces of shrapnel as proof of who fired the rounds.

“But the government does not do its work. It doesn’t care about artillery shells falling or who burns houses,” he said, referring to dwellings burnt in Tha Mee Hla village in his constituency.

According to the Rakhine Ethnic Congress, five villages were set ablaze in Rathedaung, including Tha Mee Hla, from Dec. 2018 to Feb. 2, 2020.

In January last year, Maung Naing Soe, a 7-year-old boy from Tha Mee Hla, died from shrapnel wounds after Myanmar military troops fired into the village after being ambushed near the village on Jan. 26, 2019. The boy died from his wounds while being transported to a hospital in Yangon from Sittwe on Jan. 28, 2019.

Several other children in Minbya also died after being hit by shrapnel when artillery shells struck their homes last year.

The lawmakers did their work, seeking answers and urging the government to investigate the case, but no inquiry has been held yet, said U Tin Maung Win.

Following the mass injury of schoolchildren last week, over 100 Myanmar civil society groups called on armed groups to take responsibility for civilian victims.

On the same day, the UK Embassy urged both sides in the armed conflict to end the fighting in order to bring an end to such civilian suffering.

On Feb. 14, the embassies of the United States and Canada issued statements expressing their sadness over the incident on Myanmar’s Children Day.

The UK and Canadian embassies also called on both armed groups to cease hostilities and to ensure that citizens are protected.

The local office of the UN children’s agency, UNICEF Myanmar, called on the Tatmadaw and the AA to respect school zones and “to prevent any interference of armed actors with education infrastructures, personnel and students, in line with national legal frameworks such as the Child Rights Law” and other obligations under international law.

The Feb. 13 shelling was similar to previous incidents in which artillery shells have struck civilians’ homes, killing or injuring local residents, with no one claiming responsibility.

Over the past four months, the fighting in Buthidaung, Ratheduang, Kyauktaw, Mrauk U, Myebon, Minbya and Chin State’s Paletwa has remained intense.

AA spokesman Khaing Thukha told The Irrawaddy on Tuesday that the fighting has been fiercer in January and February this year than in the same period last year. In January, the AA clashed with military troops more than 50 times, and fighting has occurred every day this month.

He reiterated that AA troops do not attack their own people, who, the spokesman said, are “strong supporters” of the armed group in these areas.

“Only the Tatmadaw has imposed so many different restrictions on civilians, including subjecting their movement to severe scrutiny and restricting the transport of rice sacks,” the spokesman said, adding that the military does these things because it is unable to get intelligence information from the Rakhine public.

The AA attacked military trucks on the Taungguk-Ann Road in Taungguk Township, southern Rakhine State on Feb. 13, in an expansion of the territory in which it operates. It also attacked three military trucks in a village in Mrauk-U, northern Rakhine State on Feb. 15.

The AA’s ambushes continue, as do the Tatmadaw’s artillery strikes.

“We will continue to use every means at our disposal to stop the Bamar military; currently it is not easy for them to operate undercover among our people,” the AA spokesman said.

The Myanmar military also denies responsibility for civilian casualties, consistently repeating its line that civilian deaths are a by-product of the fighting between it and the AA, while occasionally directly blaming the rebels. Regarding the injuring of the 21 students in the Feb. 13 shelling of the school, the Office of the Commander-in-Chief of Defense Services said that, “The AA fired heavy weapons at the Tatmadaw column and a heavy weapon round hit and exploded in the compound of the primary school….injuring 14 boys and six girls playing in the compound.” The military put the injury toll at 20.

Military spokesperson Brigadier General Zaw Min Tun was not available for further comment on Wednesday.

Locals believe the Union government’s ban on Internet access in the area on Feb. 3 was designed to help the Tatmadaw intensify its crackdown on AA forces and those the military deems to be sympathizers of the ethnic armed group.

“As the fighting has intensified since early February, following the Internet blackout, the Tatmadaw has been clearing out local villages. At least four villages have been burned in Buthidaung and Ratheduang townships,” said U Zaw Zaw Tun, a secretary of the REC.

The Rakhine parliament speaker and the social workers said the Internet ban in five townships in Rakhine and Chin states should be lifted. The government originally imposed a ban on Internet access in nine townships for eight months last year, citing a need to reduce hate speech on social media, and security reasons.

U San Kyaw Hla said, “You can imagine what it’s like in an area without Internet access and without the presence of journalists. Our country faces enormous disparagement on the international stage, as journalists are not granted access to the conflict areas.”

He added, “Any place without Internet access or reporters is a place where human rights abusers thrive. Is our state in such a condition? We need to ask this.”

On Feb. 16, 23 civil society groups and relief groups based in Rathetaung, Buthitaung, Mrauk-U, Ponnagyun, Kyauktaw, Minbya, Myebon and Sittwe called on the government “to immediately restore access to the Internet,” saying the ban had not helped reduce the fighting.

To the contrary, they said, the Internet ban had resulted in more civilian fatalities, due to a lack of access to information on human rights abuses and health concerns.

The relief groups and members of IDP camps’ committees added that the ban “neither helps to reduce hate speech nor decreases fighting between the armed groups.”