PADANG BESAR, Thailand — The beatings were accompanied by threats: If his family didn’t produce the money, Burma refugee Abdul Sabur would be sold into slavery on a fishing boat, his captors shouted, lashing him with bamboo sticks.

It had been more than two months since Sabur and his wife set sail from Burma with 118 other Rohingya Muslims to escape violence and persecution. Twelve died on the disastrous voyage. The survivors were imprisoned in India and then handed over to people smugglers in southern Thailand.

As the smugglers beat Sabur in their jungle hide-out, they kept a phone line open so that his relatives could hear his screams and speed up payment of $1,800 to secure his release.

“Every time there was a delay or problem with the payment they would hurt us again,” said Sabur, a tall fisherman from Burma’s western Arakan state.

He was part of the swelling flood of Rohingya who have fled Burma by sea this past year, in one of the biggest movements of boat people since the Vietnam War ended.

Their fast-growing exodus is a sign of Muslim desperation in Buddhist-majority Burma. Ethnic and religious tensions simmered during 49 years of military rule. But under the reformist government that took power in March 2011, Burma has endured its worst communal bloodshed in generations.

A Reuters investigation, based on interviews with people smugglers and more than two dozen survivors of boat voyages, reveals how some Thai naval security forces work systematically with smugglers to profit from the surge in fleeing Rohingya. The lucrative smuggling network transports the Rohingya mainly into neighboring Malaysia, a Muslim-majority country they view as a haven from persecution.

Once in the smugglers’ hands, Rohingya men are often beaten until they come up with the money for their passage. Those who can’t pay are handed over to traffickers, who sometimes sell the men as indentured servants on farms or into slavery on Thai fishing boats. There, they become part of the country’s $8 billion seafood-export business, which supplies consumers in the United States, Japan and Europe.

Some Rohingya women are sold as brides, Reuters found. Other Rohingya languish in overcrowded Thai and Malaysian immigration detention centers.

Reuters reconstructed one deadly journey by 120 Rohingya, tracing their dealings with smugglers through interviews with the passengers and their families. They included Sabur and his 46-year-old mother-in-law Sabmeraz; Rahim, a 22-year-old rice farmer, and his friend Abdul Hamid, 27; and Abdul Rahim, 27, a shopkeeper.

While the death toll on their boat was unusually high, the accounts of mistreatment by authorities and smugglers were similar to those of survivors from other boats interviewed by Reuters.

The Rohingya exodus, and the state measures that fuel it, undermine Burma’s carefully crafted image of ethnic reconciliation and stability that helped persuade the United States and Europe to suspend most sanctions.

At least 800 people, mostly Rohingya, have died at sea after their boats broke down or capsized in the past year, says the Arakan Project, an advocacy group that has studied Rohingya migration since 2006. The escalating death toll prompted the United Nations this year to call that part of the Indian Ocean one of world’s “deadliest stretches of water.”

Extended Families

For more than a decade, Rohingya men have set sail in search of work in neighboring countries. A one-way voyage typically costs about 200,000 kyat, or $205, a small fortune by local standards. The extended Rohingya families who raise the sum regard it as an investment; many survive off money sent from relatives overseas.

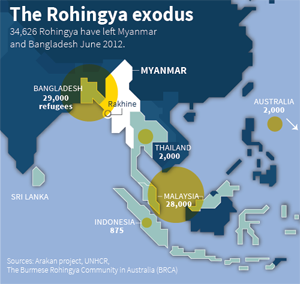

The number boarding boats from Burma and neighboring Bangladesh reached 34,626 people from June 2012 to May of this year – more than four times the previous year, says the Arakan Project. Almost all are Rohingya Muslims from Burma. Unprecedented numbers of women and children are making these dangerous voyages.

A sophisticated smuggling industry is developing around them, drawing in other refugees across South Asia. Ramshackle fishing boats are being replaced by cargo ships crewed by smugglers and teeming with passengers. In June alone, six such ships disgorged hundreds of Rohingya and other refugees on remote Thai islands controlled by smugglers, the Arakan Project said.

Sabur and the others who sailed on the doomed 35-foot fishing boat came from Arakan, a rugged coastal state where Rohingya claim a centuries-old lineage. The government calls them illegal “Bengali” migrants from Bangladesh who arrived during British rule in the 19th century. Most of the 1.1 million Rohingya of Arakan state are denied citizenship and refused passports.

Machete-wielding Arakan Buddhists destroyed Sabur’s village last October, forcing him to abandon his home south of Sittwe, capital of Arakan state. Last year’s communal unrest in Arakan made 140,000 homeless, most of them Rohingya. Burma’s government says 192 people died; Rohingya activists put the toll as high as 748.

Before the violence, the Rohingya were the poorest people in the second-poorest state of Southeast Asia’s poorest country. Today, despite Burma’s historic reforms, they are worse off.

Tens of thousands live in squalid, disease-ridden displacement camps on the outskirts of Sittwe. Armed checkpoints prevent them from returning to the paddy fields and markets on which their livelihoods depend. Rohingya families in some areas have been banned from having more than two children.

Sabur’s 33-member extended family spent several months wandering between camps before the family patriarch, an Islamic teacher in Malaysia named Arif Ali, helped them buy a fishing boat. They planned to sail straight to Malaysia to avoid Thailand’s notorious smugglers.

Dozens of other paying passengers signed up for the voyage, along with an inexperienced captain who steered them to disaster.

“Dying, One by One”

The small fishing boat set off from Myengu Island near Sittwe on February 15. The first two days went smoothly. Passengers huddled in groups, eating rice, dried fish and potatoes cooked in small pots over firewood. Space was so tight no one could stretch their legs while sleeping, said Rahim, the rice farmer, who like many Rohingya Muslims goes by one name.

Rahim’s last few months had been horrific. An Arakan mob killed his older brother in October and burned his family’s rice farm to the ground. He spent two months in jail and was never told why. “The charge seemed to be that I was a young man,” he said. Arakan State authorities have acknowledged arresting Rohingya men deemed a threat to security.

High seas and gusting winds nearly swamped the boat on the third day. The captain seemed to panic, survivors said. Fearing the ship would capsize, he dumped five bags of rice and two water tanks overboard – half their supplies.

It steadied, but it was soon clear they had another problem – the captain admitted he was lost. By February 24, after more than a week at sea, supplies of water, food and fuel were gone.

“People started dying, one by one,” said Sabmeraz, the grandmother.

The Islamic janaza funeral prayer was whispered over the washed and shrouded corpses of four women and two children who died first. Among them: Sabmeraz’s daughter and two young grandchildren.

“We thought we would all die,” Sabmeraz recalled.

Many gulped sea water, making them even weaker. Some drank their own urine. The sick relieved themselves where they lay. Floorboards became slick with vomit and feces. Some people appeared wild-eyed before losing consciousness “like they had gone mad,” said Abdul Hamid.

On the morning of the 12th day, the shopkeeper Abdul Rahim wrapped his two-year-old daughter, Mozia, in cloth, performed funeral rites and slipped her tiny body into the sea. The next morning he did the same for his wife, Muju.

His father, Furkan, had warned Abdul Rahim not to take the two children – Mozia and her five-year-old sister, Morja. The family had been better off than most Rohingya. They owned a popular hardware store in Sittwe district. After it was reduced to rubble in the June violence, they moved into a camp.

On the night Abdul Rahim was leaving, Furkan recalls pleading with him on the jetty: “If you want to go, you can go. But leave our grandchildren with us.”

Abdul Rahim refused. “I’ve lost everything, my house, my job,” he recalls replying. “What else can I do?”

On February 28, hours after Abdul Rahim’s wife died, the refugees spotted a Singapore-owned tugboat, the Star Jakarta. It was pulling an empty Indian-owned barge, the Ganpati, en route to Mumbai from Burma. The refugee men shouted but the slow-moving barge didn’t stop.

But as the Ganpati moved by, a dozen Rohingya men jumped into the sea with a rope. They swam to the barge, fixed the rope and towed their boat close behind so people could board. By evening, 108 of them were on the barge.

Mohammed Salim, a soccer-loving grocery clerk, and a young woman, both in their 20s, were too weak to move. Close to death, they were cut adrift; the boat took on water and submerged in the rough seas.

“He was our hope,” said Salim’s father, Mohammad Kassim, 71, who emptied his savings to pay the 500,000 kyat cost of the journey.

Of the 12 who died on the boat, 11 were women and children.

Mistaken for Pirates

What happened next shows how the problems of reform-era Burma are rapidly becoming Asia’s.

The tugboat captain mistook the Rohingya for pirates and radioed for help, said Bhavna Dayal, a spokeswoman for Punj Lloyd Group, the Indian company that owns the barge. Within hours, an Indian Coast Guard ship arrived. Officers fired into the air and ordered the Rohingya to the floor.

Rahim, the rice farmer, said he and five others were beaten with a rubber baton. With the help of some Hindi picked up from Bollywood films, they explained they were fleeing the strife in Arakan State. After that, everyone received food, water and first aid, he said.

Another Indian Coast Guard ship, the Aruna Asaf Ali, arrived. It took the women and children to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, an Indian archipelago a short voyage to the south, before returning for the men.

In Diglipur, the largest town in North Andaman Island, immigration authorities separated the men from women and children, putting them all in cells. Guards beat them at will, Rahim said, and rummaged through their belongings for money. He lost 60,000 kyat and hid his remaining 60,000 kyat in a crack in a wall.

Rupinder Singh, the police superintendent in Diglipur, denied anyone was beaten or robbed.

After about a month, the Rohingya were moved to a bigger detention center near the state capital Port Blair. They joined about 300 other Muslims, mostly Rohingya from Burma, who had been rescued at sea. The men went on a one-day hunger strike, demanding to be sent to Malaysia.

The protest seemed to work. Indian authorities brought all 420 of them into international waters and transferred them to a double-decker ferry, said the Rohingya passengers.

“They told us this ship would take us straight to Malaysia,” said Sabur.

It was run, however, by Thailand-based smugglers, he said.

Commander P.V.S. Satish, speaking for the Indian Navy and the Indian Coast Guard, said there was “absolutely no truth” to the allegation that the Navy handed the Rohingya to smugglers.

After four days at sea, the Rohingya approached Thailand’s southern Satun province around April 18. They were split into smaller boats. Some were taken to small islands, others to the mainland. The smugglers explained they needed to recoup the 10 million kyat they had paid for renting the ferry.

Economic of Trafficking

Thailand portrays itself as an accidental destination for Malaysia-bound Rohingya: They wash ashore and then flee or get detained.

In truth, Thailand is a smuggler’s paradise, and the stateless Rohingya are big business. Smugglers seek them out, aware their relatives will pay to move them on. This can blur the lines between smuggling and trafficking.

Smuggling, done with the consent of those involved, differs from trafficking, the business of trapping people by force or deception into labor or prostitution. The distinction is critical.

An annual US State Department report, monitoring global efforts to combat modern slavery, has for the last four years kept Thailand on a so-called Tier 2 Watch List, a notch above the worst offenders, such as North Korea. A drop to Tier 3 can trigger sanctions, including the blocking of World Bank aid.

A veteran smuggler in Thailand described the economics of the trade in a rare interview. Each adult Rohingya is valued at up to $2,000, yielding smugglers a net profit of 10,000 baht after bribes and other costs, the smuggler said. In addition to the Royal Thai Navy, the seas are patrolled by the Thai Marine Police and by local militias under the control of military commanders.

“Ten years ago, the money went directly to the brokers. Now it goes to all these officials as well,” said the smuggler, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

A broker in Burma typically sends a passenger list with a departure date to a counterpart in Thailand, the smuggler said. Thai navy or militia commanders are then notified to intercept boats and sometimes guide them to pre-arranged spots, said the smuggler.

The Thai naval forces usually earn about 2,000 baht per Rohingya for spotting a boat or turning a blind eye, said the smuggler, who works in the southern Thai region of Phang Nga and deals directly with the navy and police.

Police receive 5,000 baht per Rohingya, or about 500,000 baht for a boat of 100, the smuggler said.

Another smuggler, himself a Rohingya based in Kuala Lumpur, said Thai naval forces help guide boatloads to arranged spots. He said his group maintains close phone contact with local commanders. He estimated his group has smuggled up to 4,000 people into Malaysia in the past six months.

Relatives in Malaysia must make an initial deposit of 3,000 ringgit into Malaysian bank accounts, he said, followed by a second payment for the same amount once the refugees reach the country.

Naval ships do not always work with the smugglers. Some follow Thailand’s official “help on” policy, whereby Rohingya boats are supplied with fuel and provisions on condition they sail onward.

The Thai navy and police denied any involvement in Rohingya smuggling. Manasvi Srisodapol, a Thai Foreign Ministry spokesman, said that there has been no evidence of the navy trafficking or abusing Rohingya for several years.

Cages and Threats

Anti-trafficking campaigners have produced mounting evidence of the widespread use of slave labor from countries such as Burma on Thai fishing boats, which face an acute labor shortage.

Fishing companies buy Rohingya men for between 10,000 baht and 20,000 baht, depending on age and strength, said the smuggler in Phang Nga. He recounted sales of Rohingya in the past year to Indonesian and Singapore fishing firms.

This has made the industry a major source of US concern over Thailand’s record on human trafficking. About 8 percent of Thai seafood exports go to supermarkets and restaurants in the United States, the second biggest export market after Japan.

The Thai government has said it is serious about tackling human trafficking, though no government minister has publicly acknowledged that slavery exists in the fishing industry.

Sabur, his wife Monzurah and more than a dozen Rohingya thought slavery might be their fate. The smugglers held them on the Thai island for five weeks. The captors said they would be sold to fisheries, pig farms or plantations if money didn’t arrive soon.

“We were too scared to sleep at night,” said Monzurah, 19 years old.

Arif Ali, the family patriarch in Kuala Lumpur, managed to raise about $21,000 to secure the release of 19 of his relatives, including his sister Sabmeraz, Sabur, and Monzurah. They were taken on foot across the border into Malaysia in May. But 10 of the family, all men, remained imprisoned on the island as he struggled to raise more funds.

As Ali was interviewed in early June, his cellphone rang and he had a brief, heated conversation. “They call every day,” he said. “They say if we call the police they will kill them.”

Some women without money are sold as brides for 50,000 baht each, typically to Rohingya men in Malaysia, the Thai smuggler said. Refugees who are caught and detained by Thai authorities also face the risk of abuse.

At a detention center in Phang Nga in southern Thailand, 269 Rohingya men and boys lived in cage-like cells that stank of sweat and urine when a Reuters journalist visited recently. Most had been there six months. Some used crutches because their muscles had atrophied.

“Every day we ask when we can leave this place, but we have no idea if that will ever happen,” said Faizal Haq, 14.

They are among about 2,000 Rohingya held in 24 immigration detention centers across Thailand, according to the Thai government.

“To be honest, we really don’t know what to do with them,” said one immigration official who declined to be named. Burma has rejected a Thai request to repatriate them.

Dozens of Rohingya have escaped detention centers. The Thai smuggler said some immigration officials will free Rohingya for a price. Thailand’s Foreign Ministry denied immigration officials take payments from smugglers.

Promised Land

When Rahim, Abdul Hamid and the other Rohingya finally arrived in Thailand, smugglers met them in Satun province, which borders Malaysia.

They were herded into pickup trucks and driven to a farm, where they say they saw the smugglers negotiate with Thai police and immigration officials. The smugglers told them to contact relatives in Malaysia who could pay the roughly 6,000 ringgit.

“If you run away, the police and immigration will bring you back to us. We paid them to do that,” the most senior smuggler told them, the two men recalled.

After 22 days at the farm, Rahim and Hamid escaped. It was near midnight when they darted across a field, cleared a barbed-wire fence and ran into the jungle. They wandered for a day, hungry and lost, before meeting a Burmese man who found them work on a fruit farm in Padang Besar near the Thai-Malaysia border. They still work there today, hoping to save enough money to leave Thailand.

If the smugglers get paid, they usually take the Rohingya across southern Thailand in pickup trucks, 16 at a time, with just enough space to breathe, the smuggler in Thailand said. They are hidden under containers of fish, shrimp or other food, and sent through police checkpoints at 1,000 baht apiece, the smuggler said. Once close to Malaysia, the final crossing of the border is usually made by foot.

Abdul Rahim, the shopkeeper who lost his wife and toddler, arranged a quick payment to the smugglers from relatives in Kuala Lumpur. He was soon on a boat to Malaysia with his surviving daughter and his sister-in-law, Ruksana. They were dropped off around April 20 at a remote spot in Malaysia’s northern Penang island.

For Abdul Rahim and many other Rohingya, Malaysia was the promised land. For most, that hope fades quickly.

At best, they can register with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees and receive a card that gives them minimal legal protection and a chance for a low-paid job such as construction. While Malaysia has won praise for accepting Rohingya refugees, it has not signed the U.N. Refugee Convention that would oblige it to give them fuller rights.

Those picked up by Malaysian authorities face weeks or months in packed detention camps, where several witnesses said beatings and insufficient food were common. The Malaysian government did not comment on conditions in the camps.

The UNHCR has registered 28,000 Rohingya asylum seekers out of nearly 95,000 Burma refugees in Malaysia, many of whom have been in the country for years. An estimated 49,000 unregistered asylum seekers can wait months or years for a coveted UNHCR card. The card gives asylum seekers discounted treatment at public hospitals, is recognized by many employers, and gives protection against repatriation.

The vast majority, like Sabur, Abdul Rahim and their families, don’t obtain these minimal protections. They evade detention in the camps but live in fear of arrest.

By early July, Sabur had found temporary work in an iron foundry on Kuala Lumpur’s outskirts earning about $10 a day. He will likely have to save for years to pay back the money that secured his release.

Abdul Rahim’s family now lives in a small, windowless room in a city suburb. His late wife’s sister, Ruksana, coughed up blood during one interview, but is afraid to seek medical help without documentation.

By early July, Abdul Rahim had married Ruksana. He was picking up occasional odd jobs through friends but was struggling to pay the $80 a month rent on their shabby room. Despite that, and the loss of his first wife and daughter, he still believes he made the right decision to flee Burma.

“I don’t regret coming,” he said, “but I regret what happened. I think about my wife and daughter all day.”