RANGOON — The resurgence of the illicit drugs trade in Burma in recent years is the result of flawed drug control policies by Burma and its neighbors, a new report says. It urges regional governments to reform their repressive policies in order to better address the trade’s underlying causes, such as rural poverty, and the impact of a rise in drug use.

The report by the Amsterdam-based Transnational Institute (TNI), titled “Bouncing Back-Relapse in the Golden Triangle,” was released Monday and is based on hundreds of interviews with farmers, drug users and drug traders in Burma, Laos, Thailand, China and Northeastern India held between 2009 and 2013.

TNI said the increase in opium production in Burma, which grew for a sixth consecutive year in 2013 after seeing a sharp decline in the first half of the last decade, followed the implementation of “drug control policies [that] have failed to reduce consumption and production and instead led to more dangerous forms of drug use, growing human rights abuses and impoverishment.”

“The ASEAN strategy to become ‘drug free’ by 2015 is failing dramatically,” said the institute, which has long studied drug policy issues in Burma and across the world. “In the last decade, opium cultivation in the region has doubled, drug use—especially amphetamines—has increased significantly, and there remain strong links between drugs, conflict, crime and corruption.”

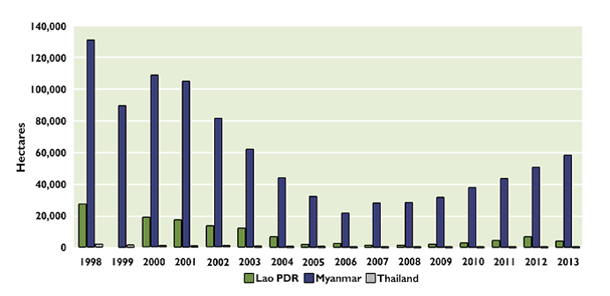

Burma is Asia’s most important hub for opium and methamphetamine production, most of which is destined for China and Thailand. Between 2006 and 2013, the area under opium poppy in Burma rose from 24,000 hectares in 2006 to 58,000 hectares in 2013, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimates, making Burma the world’s second-largest opium producer after Afghanistan, where 209,000 hectares were under poppy last year.

Opium and methamphetamine has long been produced in northern Burma, where the trade is directly tied to the country’s decades-old ethnic conflict, which continues to fester in many parts of Shan and Kachin states.

Tens of thousands of poor ethnic farmers grow the opium, while ethnic Chinese syndicates are believed to control and finance the drug trade and trafficking, according to TNI. All parties involved in the ethnic conflict—rebel groups, the Burma Army and pro-government militias—are taxing the drug trade to fuel the war, TNI said, adding that some militias and rebel groups are directly involved in drug production and trade.

From 1998 to 2006, opium production had been in decline after Burma’s former military regime and several ceasefire groups, such as the ethnic Wa, Kokang and Mongla rebels, enforced bans on poppy cultivation in northern Shan State after Burma came under growing international pressure to stem the flow of drugs.

But TNI said opium production had since relocated to southern Shan State and Northeastern India, where it has been rapidly expanding, spurred on by rising prices for the drug. “Opium bans … have had little permanent effect because opium is often the only crop viable to compensate for food shortages and high levels of poverty” among ethnic subsistence farmers, the report said, adding that the ongoing conflict is also fueling the drug trade.

The UNODC estimates that the average opium production in Burma was 15 kg per hectare in 2013, and that farmers on average earned US$520 per kg of opium in 2012.

“Until regional governments and the international community properly addresses poverty, conflict and rising demand for heroin in China, opium bans and eradication will continue to fail,” researcher Tom Kramer said in a press release. TNI said poppy farmers needed alternative livelihood options and better protection of land rights, and that they should be consulted over the impact of drug control policies.

The institute said drug use problems have also worsened in recent years. It warned of “a heroin ‘epidemic’ in Kachin State and Northern Shan State and related social and health issues including [the spread of] HIV and hepatitis C.” Harsh government policies targeting drug users have resulted in the arrests of thousands of users.

TNI called for reforms to Burma’s drug control policies, decriminalization of drug use and an increased focus on health and human rights of drug users and poor opium growers. It noted that President Thein Sein’s reformist government in recent years has shown an interest in finding alternative ways of reducing opium cultivation and drug use problems.

Local civil society organizations have complained for years about the heavy social impact drug use is having in Shan and Kachin states.

Ethnic Palaung groups have sounded the alarm over a drug use epidemic in their communities in northwestern Shan State, where in some cases up to 90 percent of the young male population is reportedly addicted to opium or methamphetamines.

A rights activist familiar with the situation in Palaung areas said authorities had reacted by briefly locking up users, but were powerless against armed gangs—often pro-government militias—producing and selling drugs in the area.

“They are not going after the big people behind the drugs—this has a big impact on the people on the ground,” said the activist, who requested anonymity for fear of retribution by drug gangs.

“After 2010, drug use in the villages sharply increased. In one village I visited, seven women came up to me crying. They said: ‘Help us, my son is a drug addict, my husband is a drug addict.’”

“[But] the thing is, who can we approach? In Shan State alone, we have six drug lords who are MPs with the ruling party. They are in the system, in the government, so it’s very hard to approach the government,” the activist said, referring to pro-government militia leaders who were made lawmakers in the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) during the previous military regime.