RANGOON —The family of a young woman shot dead by the Burma Army during the 1988 Uprising has at last been able to put her soul to rest. Win Maw Oo’s Buddhist funerary rites were performed 28 years after her death—because the young woman’s dying wish for democracy to come to Burma was considered fulfilled.

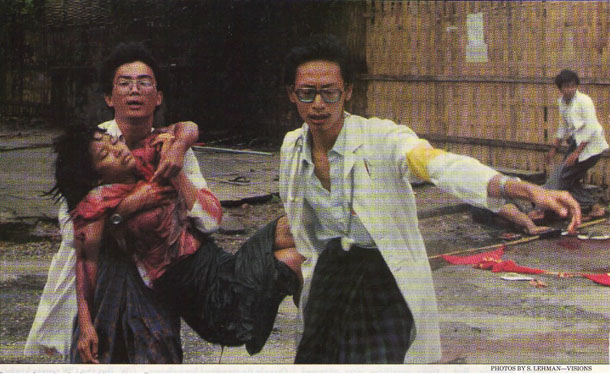

Win Maw Oo is remembered as the blood-soaked young woman pictured being carried away by two medics during the 1988 crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrators in Rangoon. That photograph, which appeared in the Oct. 3, 1988 issue of Newsweek’s Asia edition, became an iconic testament to the brutal event.

At the time, after learning that she had been shot down and left unconscious, her father frantically searched the wards of Rangoon General Hospital to find her. From what turned out to be her deathbed, then 16-year-old Win Maw Oo begged her father not to perform the Buddhist last rites until “Burma enjoys democracy.”

The request was difficult for her family to accept: Burmese Buddhists share a deeply rooted belief that a person’s soul cannot rest in peace until his or her name is called out by the family, in order to share their merit with the deceased. It was painful for them, believing that their daughter’s soul was wandering in limbo for nearly three decades.

Now with an elected civilian government in office, on Sunday Win Maw Oo’s parents were finally able to perform the rite of calling out the name of their deceased daughter, known in Burmese as a hmya pay, in order to bestow peace on her restless soul.

Win Maw Oo’s father, Win Kyu, said the family wanted to put her soul to rest so much that he pleaded with people to cast their votes for Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy, during the campaign period for the general election last year.

“Now that we have a civilian government, and political prisoners and student activists have been released, we considered it time to perform the ritual for our daughter,” he said, after the a hmya pay ceremony at the family home in Hlaing Tharyar Township on the outskirts of Rangoon.

The 64-year old noted that, with the 2008 Constitution yet to be amended, Burma today does not enjoy full democracy.

The 2008 Constitution preserves the military’s frontline role in governance—with control over the key ministries of Home, Defense, and Border Affairs, and a 25 percent bloc in both the national and regional parliaments—and secures the military’s sovereignty over its own affairs, without civilian oversight.

“At least now we have a civilian government that we elected. If we have to wait longer [for the constitution to be changed], we are not sure we will make it, given our old age,” the father added.

Khin Htay Win, the mother of Win Maw Oo, said she felt delighted that Burma today is on the road to democracy in the way her daughter had wanted to see.

“As parents, today we feel relieved, as we finally put her soul to rest,” the mother said. “But as a mother who has lost her daughter, I feel sad at the same time.”

The Irrawaddy’s Thuzar contributed reporting.