When it comes to the Myanmar regime’s international partners, all eyes are on China and Russia for their cozy relations with the junta and their constant protection of the military rulers at the UN Security Council by vetoing critical resolutions proposed by the West.

A country that has largely been off the radar so far though is Japan.

When Deputy Prime Minister of Japan and Minister of Finance Tarō Asō had a discussion with his counterpart from a member country during the G7 Finance Ministers’ meeting in London in early June this year, the topic discussed was reportedly Myanmar under military rule.

According to the Japanese daily Asahi Shimbun, the minister said other countries could rely on Japan when it came to Myanmar’s politics, as there is a Japanese person with a good relationship with Myanmar junta chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing.

The deputy prime minister’s reliable person on the Myanmar issue is Hideo Watanabe, the chairperson of the Japan Myanmar Association (JMA). Founded by Watanabe in March 2012, the JMA is a private group launched to rally support for the wave of Japanese investment in the Southeast Asian country. The association includes retired government bureaucrats and business executives and members of big Japanese companies, and has more than 100 member firms. Asō is the supreme adviser to the association.

Following the military coup in Myanmar on Feb. 1 this year, Japan stressed that it was the only communication channel with the Myanmar military and asked the junta chief for the release of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and other detainees. On Feb. 5, the Japanese government told the international community that it had many different channels for its relations with the military.

But unlike Beijing and the Kremlin, Tokyo condemned the coup and has put on hold new official development assistance for the Southeast Asian country in response to the takeover, though it has not imposed sanctions on individuals and groups involved as the US and other Western nations have done.

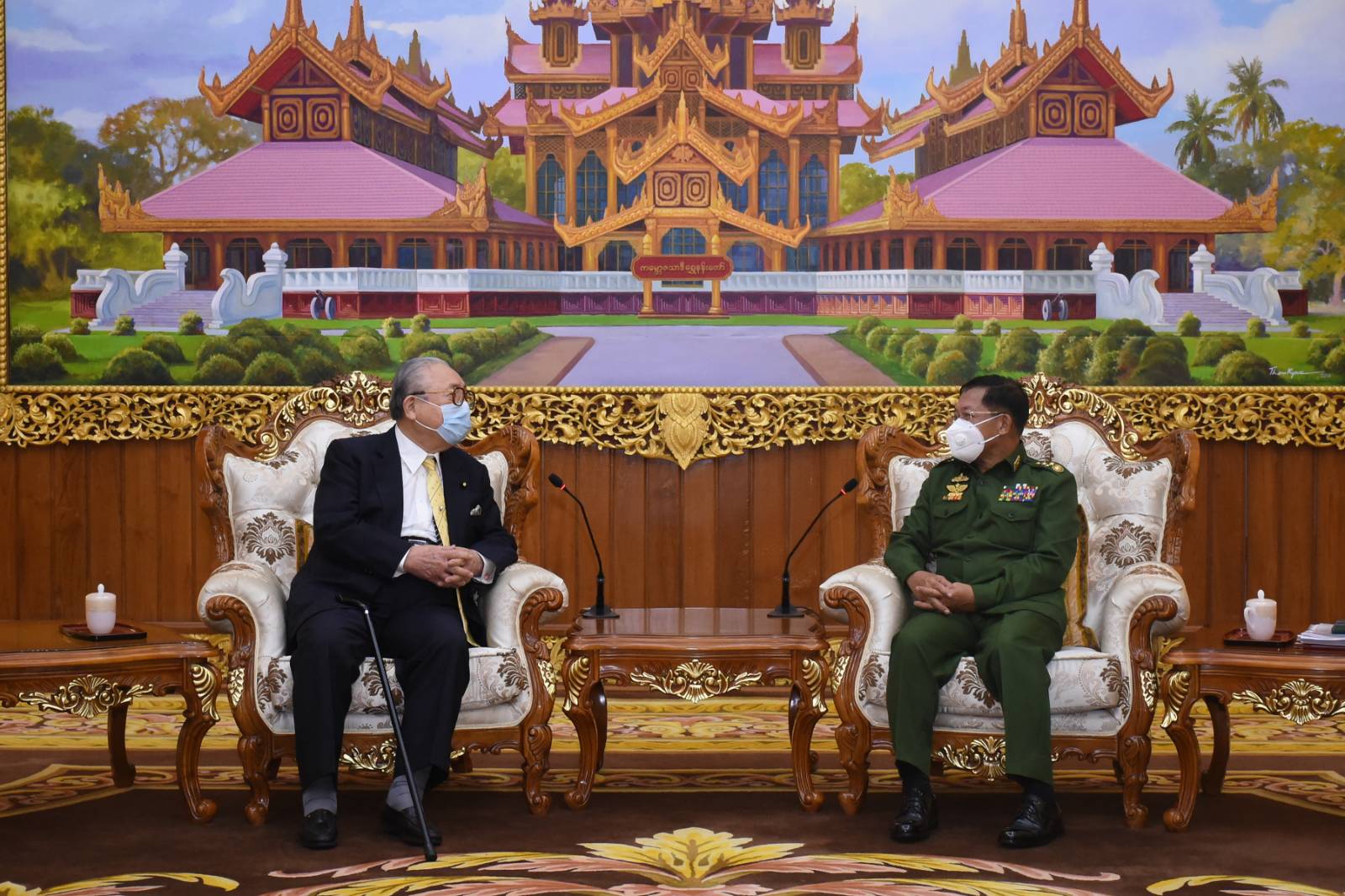

When the international community was caught by surprise by the Myanmar military coup in February and testing the waters on how to respond it, the 87-year-old flew to the country’s capital Naypyitaw seven days after the takeover.

He was escorted to the Presidential Residence to meet with the coup leader Min Aung Hlaing.

Watanabe was warmly welcomed by his host on the second floor of the residence. The general told him that he had to resort to the coup and to “please understand him.”

“I have met with Min Aung Hlaing three times and talked to him on the phone five or six times since February. There is no one who can go between like myself,” he told the paper.

The JMA chairman was also in Myanmar in January. During their meeting at the time, Min Aung Hlaing told him that the Daw Aung San Suu Kyi-led National League for Democracy simply won the election because it rigged the votes.

The friendship between Min Aung Hlaing and Watanabe is nearly 10 years old. According to Japanese sources close to the chairman, there are only two Japanese who have direct access to the Myanmar general: Watanabe and the Nippon Foundation’s Yohei Sasakawa, the Japanese special envoy for national reconciliation in Myanmar.

The paper said the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs believed the JMA chairperson is an important person who has access to the inner circle of the Myanmar military.

Who is Watanabe?

Watanabe was first assigned to provide aid to Myanmar in 1987 and began his involvement with the military afterwards. He continued his relations with Myanmar even when the country was under military rule after the pro-democracy movement was crushed and state power was seized by the military in 1988. He became friends with Thein Sein, then a military commander in Shan State, who was later promoted to general. In 2011, Thein Sein, by then a civilian, took office as the president of Myanmar.

The JMA chairperson met with President Thein Sein at the Presidential Palace in Naypyitaw the same year as the latter was sworn in. During the meeting, the president allowed the construction of Thilawa Port in Yangon to be run by Japanese firms.

The next day, Watanabe met Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing to check if the commander-in-chief agreed with the fact that the port construction would be taken care of by Japan. Later, as the relations went smoothly, at least 50 meetings were held between the two.

After obtaining permission for port construction and returning to Japan, the JMA chief held discussions with the prime minister and other officials. Subsequently, 500 billion yen that Myanmar owed to Japan was written off and Japanese official development assistance (ODA) that had been suspended when Myanmar was under military rule was resumed.

The Thilawa Port, which was based on ODA and cost a huge amount of money, was able to open in September 2015.

The amount of Japanese investment in Myanmar escalated with the completion of the port.

In his meeting with Asō, the then deputy prime minister of Japan, in 2013, Watanabe told the deputy that the Myanmar military wanted to continue its relations with him alone.

In his interview with the Japanese paper, Watanabe said he had established relations with the Myanmar military at “the directive of Prime Minister Abe and Deputy Prime Minister Aso since 2013.”

Regime apologist

In late May, with the number of Myanmar civilians killed by the regime exceeding 800, Watanabe’s son Yusuke, who is the secretary general of the JMA, wrote in The Diplomat that Min Aung Hlaing’s coup was constitutional and stressed the need for Japan to continue to boost its “special relationship with the Tatmadaw”. The Tatmadaw is Myanmar’s military.

In several interviews with the Asahi Shimbun, Hideo Watanabe said Min Aung Hlaing didn’t stage a coup and “he did what he should in accordance with the law.”

Watanabe insisted that he was not siding with the military but “didn’t want people to say that the military was suppressing and killing its own citizens.” He said he believed Min Aung Hlaing would bring a genuine democratic system to Myanmar, because he was told so.

Yuka Kiguchi of Mekong Watch told The Irrawaddy that Watanabe’s statement was also contrary to the resolution condemning the military coup in Myanmar which was adopted by both Houses in the Japanese parliament.

“Japanese people reject Mr. Watanabe’s support for the Tatmadaw. Businesspeople who are not members of the Japan Myanmar Association have criticized his arrogant remarks. I strongly reject his comments,” said the executive director of the Tokyo-based advocacy NGO, which addresses and prevents the negative environmental and social impacts of development in the Mekong region, which includes Myanmar.

For all his personal ties with Min Aung Hlaing, Watanabe’s effort seemed to bear no fruit while the Japanese government’s attempts to sway the Myanmar military based on previous good relations have been in vain.

During the meeting on Feb. 8, he told Min Aung Hlaing not to use live bullets on protesters. The latter reportedly agreed. The next day, a protester was shot in the head with a live bullet. There was also a contradiction between Watanabe and the Japanese Foreign Ministry. While the ministry said it condemned “the military coup in Myanmar” in the G7 Foreign Ministers’ statement on Myanmar on Feb. 3, the JMA chairman insisted that there had been no coup.

Toshimitsu Motegi, Japanese minister for foreign affairs, criticized the shooting of protesters in Myanmar in his online meeting with US Secretary of State Antony Blinken on Feb. 10. He also conveyed Tokyo’s demands that the Myanmar military junta stop the brutal killing of civilians, release detainees and rebuild a genuine democratic system. In Myanmar, Japanese Ambassador Ichiro Maruyama met with Wunna Maung Lwin, minister for foreign affairs for the ruling military, to submit the same demands. Nothing happened.

Watanabe visited Myanmar again in May and stayed until early June. During his time in the country, he met with Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing twice. He said the junta chief told him he would bring about a democratic system in the country and hold an election within the next two years. Watanabe seemed to believe what he was told. In fact the election organized by the coup leader Min Aung Hlaing will have no space for Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and her party, the National League for Democracy, as the junta is trying to disband it. Recently, the junta canceled the NLD’s sweeping 2020 electoral results, attracting fury from Japanese Foreign Minister Motegi, who said “the development is not preferable because it goes against the realization of a swift return to the democratic process that Japan has been demanding.”

At a press conference after the ministerial meeting on June 1, journalists asked if Watanabe was assigned by the Japanese government to handle Myanmar and Motegi said no. It seems like a clear line between the government and the individual who has been considered the communication channel for Tokyo, meaning that the Japanese government’s favor of Watanabe for his personal ties to the Myanmar coup leader is now waning.

“It appears so, but because he is not a member of parliament any more, his political power has probably diminished,” said Kiguchi. Watanabe used to be the minister of posts and telecommunications, representing the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), and has close personal contacts with many party members.

Meanwhile in Tokyo, Watanabe has been a frequent target for Myanmar democracy activists.

In May and August, Myanmar people in Japan staged protests against him in front of the JMA office.

Ko Thant Zaw Tun from Revolution Tokyo Myanmar, which organized the protests, said Watanabe is protecting the regime.

“He covered up the coup and made wrong reports about Myanmar to the Japanese government. They caused Japan’s responses to Myanmar issues to be less effective,” he said.

You may also like these stories:

China Invites National League for Democracy to Summit for Asian Political Parties

Myanmar Junta Reports Increasing Attacks by Resistance

Myanmar Military Telecom Towers Attacked by Resistance Fighters