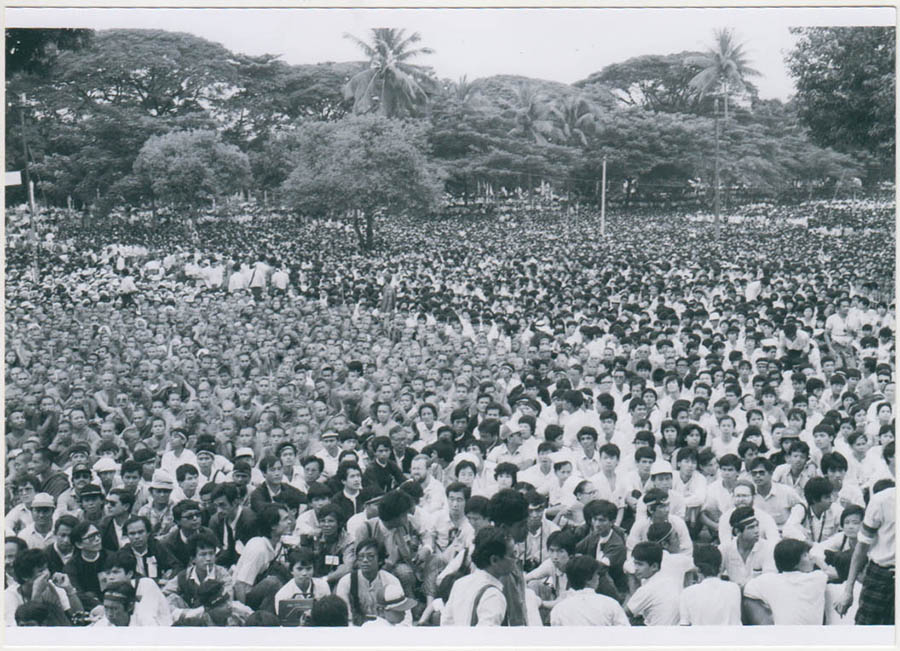

YANGON — Almost 30 years later, the immensity of the crowd he saw still excites him.

On the morning of Aug. 26, 1988, Htein Win picked up a camera that he had borrowed from a friend and headed to the western gate of Yangon’s Shwedagon Pagoda, where Daw Aung San Suu Kyi began her decade-long campaign against the Burmese military regime by addressing the people and stating that “the entire public entertains the keenest desire for a multi-party democratic system of government.”

“Whenever I think about it, the thing that pops into my mind is the sea of people,” Htein Win recalled recently.

Mesmerized by the number of people, he knew he had to do something. Shortly before Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s arrival, he climbed onstage and captured the scene with his camera. When she delivered her speech, he clicked the shutter again. Three decades later, both pictures—throngs of people filling the pagoda’s compound as far as the eye can see and the then 43-year-old Daw Aung San Suu Kyi delivering her speech with students standing guard in the front row—are still some of his favorites.

“I feel that I was able to document some important moments in Myanmar’s history,” the photographer explained.

Apart from capturing the democracy icon’s political debut, Htein Win, 72, is also one of the few local photographers who documented the popular uprising in 1988 from July until the military’s takeover in September.

Out of several hundred pictures that he took at the time—left untouched for more than two decades due to government censorship of all printed materials—he will showcase 100 pictures for the first time at the photo exhibition “8888 The Uprising” in Yangon next month when the uprising turns 30. Some of the pictures have circulated online, but this will be the first exhibition in Myanmar in which they are featured.

Named after a nationwide protest against then Ne Win’s single-party dictatorship on Aug. 8, 1988, the 8888 Uprising was a major shift in modern history in Myanmar. Political analysts at home and abroad agree that despite its end in a bloody military coup, it raised the people’s political awareness that paved the way for changes that brought the Daw Aung San Suu Kyi-led National League for Democracy to power 28 years later.

Htein Win followed the protests as they gathered momentum while people from every walk of life joined the rallies across Yangon.

“At first, I was reluctant because I thought I might be arrested. But given the intensity of the protests and everyone’s participation, I no longer cared about the punishment,” he said.

From July to September 18, the day the military staged a coup, he wandered around the streets of Yangon with a camera in hand from morning to dusk. As a result, he was able to take pictures of protests attended by not only students also but actors, actresses, journalists, monks, writers and even soldiers.

He said he covered the protests because he noticed that they were significant, as they were attracting more public participation and becoming a popular uprising.

“In the past, we had some protests by students and workers for their rights. But the ’88 ones were more unusual. Nearly everyone joined in and they had one message: Democracy,” he explained.

Apart from the ’88 Uprising, Htein Win was able to capture another important moment in history. When the government cracked down on a student demonstration calling for a state funeral for the late UN Secretary General U Thant in December 1974, he was at Yangon University campus to witness the violence and shoot some pictures. Those images saw the light of day 40 years later in 2014 when Myanmar no longer practiced pre-publication censorship.

As for the ’88 Uprising, he says he doesn’t have any photos of the military’s bloody crackdown on protesters following the coup. When he heard the takeover announcement on the afternoon of Sept. 18, he knew trouble was on the way. The first thing he had to do was hide several hundreds of negatives taken over months because if he were caught with them, he would face prison and possibly torture. He asked some of his friends to hide some of the negatives but they were too afraid, as the military cracked down on many people on suspicion of involvement in the uprising.

“Some burned the negatives or threw them away,” the photographer recalled with an air of sorrow.

It was a fate that other people who covered the uprising faced as well. As a videographer, U Sonny Nyein documented the protests as Htein Win did. His footage included Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s first public speech at Yangon General Hospital on August 24. Most of his videotapes were damaged by the wear and tear of time while being kept in secrecy.

“Most people who covered the uprising destroyed their negatives as they were afraid of retribution. Now we only have Htein Win’s pictures. They are historic,” U Sonny Nyein said.

Even though some of his negatives were destroyed, Htein Win managed to smuggle some of them out of the country with some friends’ help. They landed at an international archive in Amsterdam until now, and the 100 pictures to be featured at the exhibit were selected from those remaining in the archive to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the uprising.

He believes his pictures are historical records to let young people who were born after 1988 know what happened in the country three decades ago, as images are sometimes more convincing than words.

“I am glad to see the pictures made public before I die,” the 72-year-old said.

‘8888 The Uprising’ photo exhibition will be open to the public from Aug. 8 to 12 at Beik Thano Art Gallery in Bahan Township in Yangon. Admission is free.