Pauk-Phaw and its Evolution

“Pauk-phaw” was a term coined in the 1950s to describe the supposedly friendly and close relationship between China and Burma. It may be translated as “fraternal” but, according to Burma expert David Steinberg, it “has a closer Chinese connotation of siblings from the same womb [and] was used uniquely for Burma.” A memorial to honor the pauk-phaw relationship was erected in Mangshi in China’s Yunnan province in 1956 and the term was invoked as recently as September 2010, when Burmese junta leader Snr Gen Than Shwe paid an official visit to China.

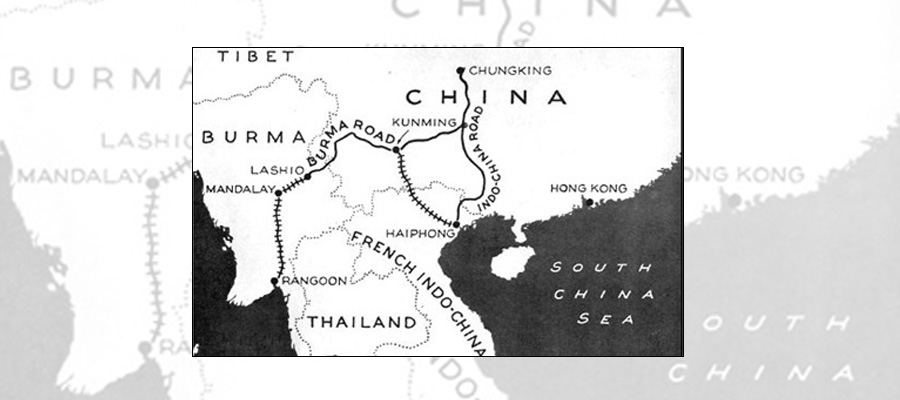

But despite such diplomatic niceties, relations between China and Burma have not always been especially cordial. China, a vast, mainly inland, empire, has always looked for outlets to the sea for its land-locked western and southwestern provinces. That policy began as far back as the 18th century and manifests itself today in the “One Belt, One Road” development strategy proposed by Chinese leader Xi Jinping to open new trade routes between China and Eurasia. The Burma corridor gives China access to South- and Southeast Asia as well as the entire Indian Ocean region, and has, therefore, always been of utmost strategic importance to whoever is in power in China.

In the 1760s, the Chinese Qing Dynasty launched four military expeditions against Burma in order to occupy the country. The Chinese were driven back after suffering extremely heavy casualties and the successful defense of the Burmese kingdom laid the foundations for today’s boundary between the two countries. Burma survived as an independent nation until the arrival of the British in the 19th century. British colonization kept the Chinese even more firmly at bay, however, a new era in bilateral relations was ushered in after Burma became an independent republic on January 4, 1948 and Mao Zedong’s communists proclaimed the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on October 1, 1949.

After that, relations between China and Burma may be divided into five periods. In the first from 1949 to 1962, Beijing maintained a cautiously cordial but basically friendly relationship with the non-aligned, democratic government of Prime Minister U Nu, which ruled Burma from independence until Gen. Ne Win and the army seized power in a coup d’état on March 2, 1962. In the second period, during the first sixteen years of Ne Win’s rule, Beijing actively supported the armed struggle of the insurgent Communist Party of Burma (CPB). China poured more arms and ammunition into the CPB than to any other communist movement in Asia outside Indochina. Following policy changes in China after the death of Mao in 1976, and the return to power of Deng Xiaoping in 1978, the third period began as Beijing sought rapprochement with the government in Rangoon.

At the same time, however, support for the CPB continued albeit on a much reduced scale. The fourth period of relations came after the Burmese military’s suppression of a nationwide pro-democracy uprising in Burma in September 1988 and the formation of a junta initially called the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) and then the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC). When Western nations imposed sanctions on Burma, the relationship with China began to be characterized by genuine cooperation as China ramped up economic ties and politically shielded the rights-abusing military regime from international criticism. This arrangement allowed Beijing to make deeper economic and political inroads into Burma than at any previous time.

The fifth period began in 2011, when a new, quasi-civilian government led by former general Thein Sein took over and began to steer the country away from its heavy dependence on China, which had begun to alarm many fiercely nationalistic Burmese army officers. Relations with the West improved—and China’s response to this new and unexpected situation came in two different forms: 1) continued support for the Burmese government, and 2) support to certain insurgent groups fighting the regime. This strategy may appear superficially contradictory, but it is a system that, under examination, has its own logic.

China may have transformed its economic system from rigid socialism to free-wheeling capitalism, but politically, it remains an authoritarian one-party state where the Communist Party of China (CPC) is above the government and military. The old policy of maintaining “government-to-government” as well as “party-to-party” relations has not changed. Even while trade with China continues to boom and the Chinese are selling fighters-jets and other military hardware to Burma, “party-to-party” relations continue to be maintained with the United Wa State Army (UWSA), the successor to the CPB. The UWSA today is better equipped, with Chinese-supplied weaponry, than the old CPB army ever was. The UWSA serves as a “stick” in China’s relationship with Burma while diplomacy and promises of aid, trade, and investment are the “carrot.” As China sees it, it cannot simply “hand over” Burma to the West. The country is far too important strategically and economically to the PRC for that to happen.

1949-1962: The “Pauk-Phaw” Years

The relations between China and Burma in the late forties were troubled by a disputed and largely un-demarcated border, illegal immigration into Burma by vast numbers of Chinese laborers, businessmen and even farmers in search of greener pastures, and smuggling. Relations became even more uncertain when large numbers of Nationalist Chinese Kuomintang (KMT) troops of the Republic of China (ROC) retreated into Burma’s north-eastern hill areas following their defeat in the Chinese civil war.

From clandestine bases in remote border mountains that were not under the control of the central Burmese government, these Kuomintang forces launched a secret war against China’s new Communist government, supported by the ROC government on Taiwan, the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and Thailand. There was a definite possibility of a war between the PRC and the unwilling host to these forces. However, the Sino-Burmese relations that developed from this initial possibility of conflict provides a good example of how a small, comparatively weak country worked to preserve its independence and neutrality in dealing with the largest and then most powerful nation in Asia. Burma’s independent foreign policy vis-à-vis China was all the more remarkable considering that successive Chinese governments, regardless of their political nature, always considered Burma to be a vassal state and the pre-colonial Burmese kings often had to send tribute missions to the Chinese Emperor.

A breakthrough came in early 1953 when Burma decided to take the matter of the Kuomintang presence on its soil to the United Nations. Prior to that, the fledgling Burma Army had fought several decisive battles against the Kuomintang, which clearly demonstrated that these guests were not camping on Burmese territory with the consent of the government in Rangoon. On April 22, 1953 the UN adopted a resolution demanding that the Kuomintang lay down their arms and leave Burma. Although thousands of Nationalist Chinese soldiers were evacuated to Taiwan, the UN resolution was thwarted as Rangoon was unable to stop the provision of reinforcements to remaining forces via secret airstrips in north-eastern Burma in aircraft provided by the CIA.

Regardless, the U Nu government had made its point, and on April 22, 1954, the PRC and Burma for the first time signed a bilateral trade agreement. On June 28-29, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai visited Burma at the invitation of the Burmese government and held talks with U Nu. A joint Sino-Burmese declaration was signed by the two leaders on June 29, endorsing the “Five Principles of Peaceful Co-existence”: Mutual respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty, non-aggression, non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, equal and mutual benefits, and peaceful coexistence.

Even though this policy was labeled pauk-phaw, in reality, Burma adopted a neutral stand on foreign policy, with the ultimate aim of preventing China from interfering in its internal affairs. The concept pauk-phaw relied on a deeply asymmetrical “friendship” between China—a huge and often threatening regional superpower—and Burma, a much smaller country on its periphery. The first years of Burmese independence were marked by widespread insurgencies, and the CPB was one of the major rebel forces. Although the CPB had strong Maoist tendencies as early as the fifties, Beijing refrained from supporting it.

The next issue to settle was the disputed Sino-Burmese border, which U Nu discussed in detail during a September 1956 visit to China. He returned with a tentative plan for a settlement that called for Chinese recognition of Burmese sovereignty over the so-called Namwan Assigned Tract in exchange for ceding to China three villages in Kachin State: Hpimaw, Gawlum and Kangfang. China also pledged to recognize Burmese claims on the remainder of the 1,357-mile frontier.

U Nu’s concessions provoked protests from both Burmese politicians and ethnic groups such as the Kachin, who rose up in rebellion in 1961 as a direct result of the border talks with China. However, negotiations continued for nearly four years until an agreement was eventually signed on January 28, 1960.

In 1958, U Nu was forced to hand over power to a military caretaker government, headed by army chief General Ne Win, who concluded the border agreement and signed a treaty of friendship and mutual non-aggression with China. In addition to the three Kachin villages (59 square miles), Ne Win also ceded the Panhung-Panglao area of the northern Wa Hills (173 square miles). In return, the Namwan area (85 square miles), which for all practical purposes was part of Burma anyway, formally became Burmese territory. More importantly, though, China did renounce all its claims to areas in northern Kachin State. Until that time, Chinese maps had shown the border to be just north of the Kachin State capital of Myitkyina and Taiwanese (ROC) maps still show the border at that point, since Taipei has never recognized any agreements signed between the communist government in Beijing and other nations.

Following a general election in February-March 1960, U Nu returned to power. With the border now demarcated, Burma launched a new offensive against the Kuomintang forces in north-eastern Burma the following year. This time, thousands of Chinese troops of the Chinese Communist Party’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) also crossed the border into Burma near the town of Mong Yang north of Kengtung in eastern Shan state, where the Kuomintang maintained a major base. Mong Pa Liao, another Kuomintang base near Burma’s border with Laos, was also attacked in a campaign that was clearly coordinated with the Burmese military. It is reasonable to assume that this was part of the new “friendship agreement” between the PRC and Burma as well, although it has never been admitted officially.

Tomorrow: Part 2. ‘Brothers no More’

This article was originally published here by The Project 2049 Institute, a policy group based in the US.