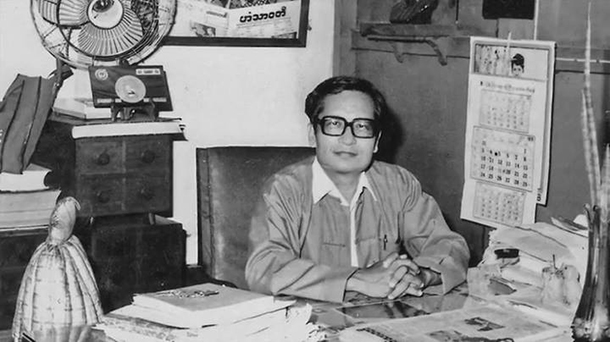

After throwing him in prison, authorities searched Win Tin’s room in Rangoon, where they found books that were later displayed at a press conference used to accuse the veteran journalist of being “a communist.” This allegation was in keeping with the Burmese military regime’s style, fabricating charges in order to put dissidents or political rivals behind bars.

Win Tin was one such outspoken critic and victim of the junta, which launched a major crackdown against the pro-democracy opposition movement soon after government troops mercilessly gunned down hundreds of street demonstrators in 1988.

Less than a year later, he was blindfolded, handcuffed and tossed in a cell. During interrogation sessions that lasted several days without sleep, military intelligence officers routinely tortured him. The National League for Democracy cofounder would have been about 60 years old at the time.

The physical abuse caused Win Tin to lose almost all of his teeth. It took eight years to replant them in prison.

The regime pressed him to confess and at one point took him to an Armed Forces Day exhibition in Rangoon, where guards asked him to write down his feelings toward the military. As Win Tin remembers it, they provided him with dozens of sheets of paper and a pen. Win Tin walked to a corner and spent hours writing out his thoughts, handing over the papers to his captors when he was done.

Scanning Win Tin’s missive, the face of the chief intelligence officer present turned increasingly red until the man tossed the papers away in anger. Written on the sheets provided, Win Tin had simply told the army to stay out of politics, and asked the regime to solve political problems in Burma through political means.

So it was back to prison and more rounds of torture for the aging pro-democracy campaigner. It was a hellish life that he endured under Burma’s brutal military regime.

According to Gen. Kyaw Win, who served as deputy intelligence chief under Lt-Gen Khin Nyunt at the time, interrogations were usually rough, combining physical and mental torture.

Khin Nyunt, then the intelligence chief, routinely held early morning meetings at intelligence headquarters. The spy chief, who was somehow considered “reform-minded” by some Western watchers and government officials, would open the briefings with a question: “Have they confessed?”

He would then individually inquire with the senior staff officers assigned to handle political prisoner cases. His boss, Snr-Gen Than Shwe, would want to know of any and every breakthrough in breaking the opposition’s stubborn resistance.

There was no code of conduct and no supervision of interrogators. They were given a free hand to interrogate political activists and other detainees as they saw fit.

Due to maltreatment and harsh conditions at the prison where Win Tin was locked up for almost 20 years, he developed gastric problems and suffered a hernia. But regarding his health, Win Tin was relatively fortunate—other prominent writers, journalists and activists of his age died in prison. He underwent medical procedures for various health ailments while in prison, but with one particular surgery he was forced to wait five years before being granted approval for the procedure.

The regime wanted him to die, but Win Tin was well-known internationally, so pressure kept growing to free him.

In 1994, then US congressman Bill Richardson was permitted to visit him in prison. Win Tin was suffering from several medical ailments, but the American noted that his spirits were high. During his brief conversation with Richardson, Win Tin talked politics and stressed the need for a peaceful political solution in Burma.

In 2007, the UN’s Burma human rights rapporteur Paulo Sergio Pinheiro visited the country and also met Win Tin in prison. The UN diplomat was impressed by Win Tin, and later said he could not comprehend why the regime wanted such an intellectual man locked up for more than a decade. The regime did not provide any reading or writing materials to the journalist.

“Win Tin told me he is locked in his cell all day with the exception of one hour in the morning and one hour in the afternoon,” the Brazilian diplomat told Inter Press Service in November 2007.

At the time, the UN was attempting to persuade the regime to allow the International Committee of the Red Cross access to prisons in Burma. Khin Nyunt was no longer in charge, having been placed under house arrest three years earlier. Than Shwe’s team refused to free Win Tin, but did allow the ICRC limited access to some prisons.

According to former political prisoners, interrogations could last several days or weeks, without food or water. Detainees were usually kept in small, dark cells and forced to wear hoods. In the middle of the night, officers would slam the doors and enter cells before proceeding to punch and kick sleep-deprived prisoners. Win Tin was not spared this mistreatment.

But when international pressure would mount, authorities had sufficient cunning to ease up a bit, and would usually allowed some family, friends or high ranking diplomats to visit Win Tin and other political prisoners.

A former senior intelligence officer told The Irrawaddy in 2013, “There is no rule of law. They would pick up any suspects with the assumption that they were all political activists and would try to get a confession by any means.”

It was a strategy to humiliate and dehumanize people—to break their spirits. But when he was finally released from prison in 2008, Win Tin emerged unbroken.

And still, his supporters are left to wonder: If he had received better treatment and medical care in prison, might Uncle Win Tin have been with us for a few more years?