WASHINGTON — China and the United States took a major step in the fight against climate change over the weekend, but what was termed a “breakthrough” might not do much in the longer term to lock in legally binding carbon emission cuts from the world’s two biggest emitters of greenhouse gases.

Still, environmental groups and some US and global policymakers said the agreement could give fresh momentum to the United Nations’ arduous process of finalizing a global treaty to replace the Kyoto Protocol on climate change by 2015.

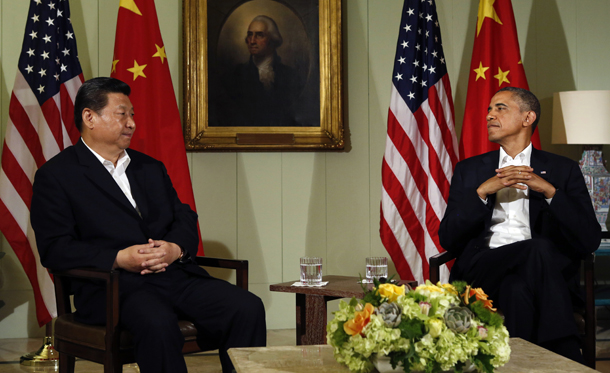

In their first talks, US President Barack Obama and Chinese Premier Xi Jinping agreed to phase out production and consumption of the gases known as hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), working under the UN’s 1987 Montreal Protocol.

Used mostly in air conditioners and refrigerators, ozone-harming HFCs make up roughly 2 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, but are rising at a rate of up to 9 percent annually.

The White House said a global phase-down could reduce the carbon dioxide equivalent of 90 billion tons by 2050, roughly two years’ worth of global greenhouse gas emissions.

“We see that as just the first step of a long and robust international climate agenda in the second term,” Heather Zichal, deputy assistant to the president for energy and climate change, said on Tuesday.

Analysts worry that the UN climate talks continue to be hampered by deep divisions between developed and developing countries over the responsibility for carbon emissions.

One official close to the negotiations said the agreement was a political breakthrough, but the road ahead to a global deal on climate change would still be long.

The official said the weekend agreement, which followed earlier talks between Secretary of State John Kerry and Xie Zenhua, a vice chairman in China’s top economic development body, can inject a dose of optimism into the UN climate talks. But the deal represents a powerful example of what can be done when two major powers work together, the official added.

Tale of Two Treaties

Experts have said addressing HFCs under the separate Montreal Protocol, regarded as a successful international treaty, can lead to major emissions reductions while negotiators hammer out parameters of a workable new climate treaty by 2015.

“This is the biggest, fastest, most effective climate mitigation that could happen in the near term,” said Mark Roberts, international policy advisor of the Environmental Investigation Agency, a group involved in climate issues.

Unlike carbon dioxide, the most prevalent and longest-lasting greenhouse gas produced across many sectors of a country’s economy, HFCs are short-lived and confined to just a handful of sectors, making them easier to tackle.

The Montreal Protocol also creates different timetables for rich and poor countries to phase out production of the gases and gives poor countries financial support to use alternatives. It has already phased out the use of 100 hazardous chemicals.

The United States, Mexico and Canada first proposed the phase-out of HFCs under the Montreal Protocol in 2009. At that point China, India and Brazil opposed the plan, arguing that HFCs should be addressed in UN climate negotiations.

Durwood Zaelke, founder of the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development, said the constraints of UN climate talks have created the need for diplomatic moves outside of that process, such as the new US-China agreement.

“This is the beginning of a movement to enlist more climate mitigation from parallel venues,” he said, adding that such deals take some pressure away from UN climate talks and open the way for other solutions.

Zaelke pointed to negotiations within the International Maritime Organization and the International Civil Aviation Organization as examples of venues where shipping and aviation emissions can be addressed untethered from UN climate talks.

The HFC agreement is “rebuilding an urgent sense of optimism” in the multilateral process that can pave the way for agreements on other short-lived greenhouse gases, such as black carbon, the soot emitted from cook stoves and diesel engines, Zaelke said.

More of these kinds of agreements could be on the horizon, those familiar with climate negotiations have said.

A US-China climate change working group formed in April is expected to come forward with a number of new proposals at the next US-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue from July 8-12.

Diplomats will also gather in Bangkok on June 24 for a week of Montreal Protocol meetings and could start negotiations on an HFC phase-down at that point.

Additional reporting by Patrick Rucker and Ayesha Rascoe.