MYEIK, Tanintharyi Division— Once virtually inaccessible to visitors, the southern port town of Myeik is slowly opening up, and there is good news for visitors who now have a helpful guide to many of its forgotten treasures.

Myeik is best known today merely as a gateway to the stunning archipelago of some 800 largely uninhabited islands that begins just minutes off its shores. But the town’s distinctive provincial seaside atmosphere and its rambling old streets dotted with evocative timeworn buildings are also full of interest.

Hundreds of years of history are woven into the present in the capital of the Tanintharyi region which came under Thai, British, Japanese, and Burmese rule at various times over some 800 years.

In its heyday, Myeik was a major gateway and a cosmopolitan hub for traders, travelers, and adventurers from the west and India who voyaged up the Tanintharyi River and beyond to reach the old Thai capital of Ayutthaya before it fell in 1767.

Along with the Tavoyans, Burmans, Karen and Mon who call the town home today, descendants of people who settled here over many hundreds of years from former Siam, Portugal, India, and China still make up a part of the town’s rich population mix and add to its unique cultural flavor.

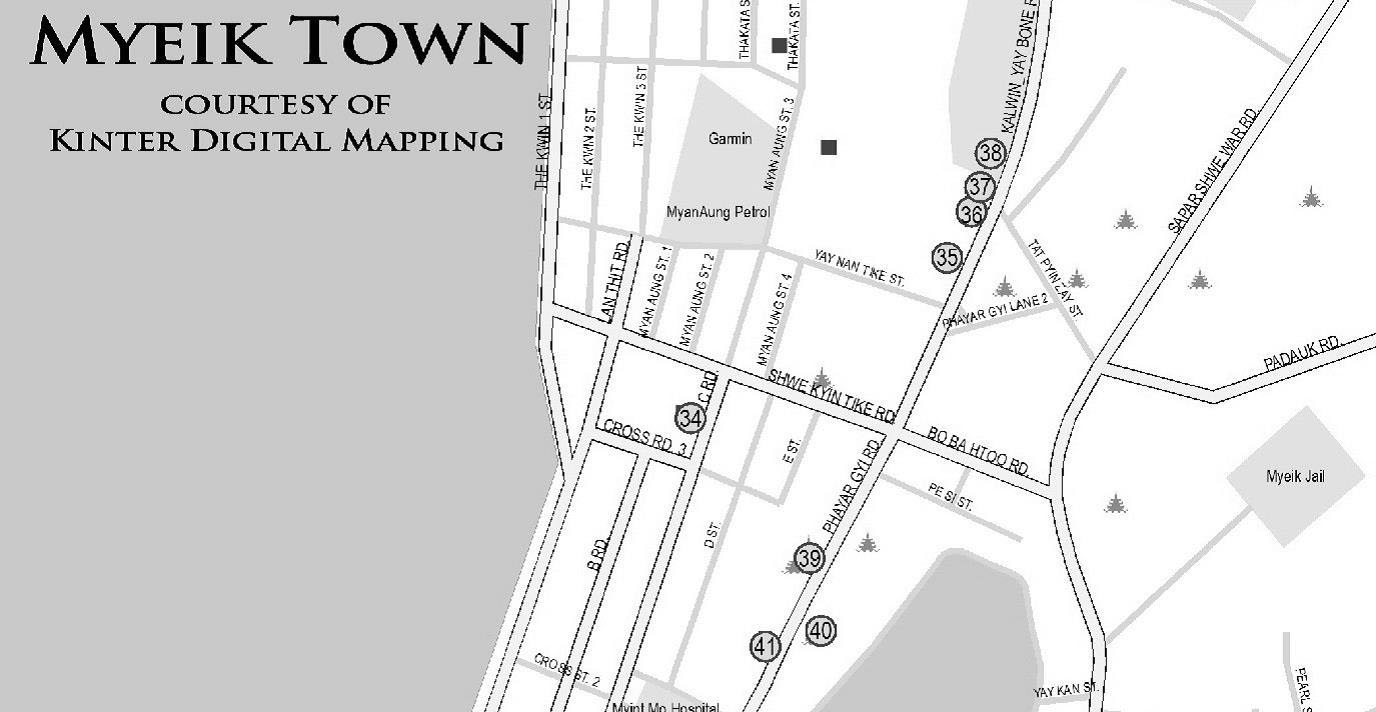

That special heritage is highlighted in the new ‘Myeik Walking Tour’ which explores more than forty distinctive old buildings and locations and provides many illuminating snippets of history, stories and anecdotes connected to them.

From the Theindawgyi temple sitting atop a high ridge commanding wonderful views over nearby islands to old colonial buildings, religious centers and the town market, a stroll or a ride around Myeik will more than reward those with an appreciation of the past.

The walking tour is a labor of love and a work in progress on the part of a researcher from the US who goes by the pen-name Felix Potter.

He said he felt there was something special about the town the first time he visited it.

“Delving into the history of the place proved that even my initial impression had vastly underestimated its importance and interest. Every time I talk to someone or find another document or reference, I discover something new about Myeik district and its principle town,” said Potter, who lives across the isthmus in Cha-Am in southern Thailand.

He hopes this first iteration of the guide will stimulate more discoveries about Myeik’s colorful past.

“Making this guide seemed like a first step towards collecting the town’s history, which has been scattered by time, war and neglect. My hope is that it will become a group project, involving residents and other researchers,” said Potter, who worked closely with local guides during the research which also took him to old archives and records.

That process of collaborative input has begun already as the guide awaits its first commercial printing.

“Some Myeik residents have already contacted me with corrections, which is actually the most pleasing result I could have imagined. If an interest in architectural preservation develops as well, that would be an added and much-needed bonus,” Potter said.

The Myeik Walking Tour is currently available on Kindle via Amazon here. Local tourism operators can also provide visitors with informal hard and soft copies, with the full blessings of the author.

Extracts from the Myeik Walking Tour

Customs House

One of Myeik’s best-preserved colonial structures, this building functioned as the port customs office. It likely dates to the 1930s. If you ask permission, it may be possible to look upstairs where the administrative offices were once located.

“There was one constant throughout the centuries of imperial rule: the firm belief that the colonies must pay for themselves, if not enrich Britain as well. Revenue from this customs house was thus very important to the government in British Mergui. [The former name of the town],” says Potter.

Residence of Mr. E. Ahmed

For several decades in the early twentieth century, Mr. Ahmed held the monopoly license for extracting pearls, mother-of-pearl, and other shells and marine products from the Mergui Archipelago. He also operated a tin mine, rubber plantations and rice mills.

Through these businesses, he grew wealthy enough to build both this magnificent home and also the large mosque on the same street. Mr. Ahmed and his son, Zakaria, were leading figures for much of Myeik’s modern history. His family continues to reside in the house that their patriarch built in the 1920s.

Assumption Catholic Church

A Roman Catholic church has existed in Myeik for centuries. For much of that time, its priests were young Frenchmen sent out by Missions Etrangeres de Paris. Records show that most died after only a year or so in Mergui, usually in their early thirties. It was once very rare for an Missions Etrangeres de Paris priest to live past forty.

The current church was built in 1862 with the sponsorship of a local Portuguese couple, George and Isabella D’Castro, whose tombstones are behind the building. Old maps show that the property once overlooked the waterfront at high tide. Thick concrete walls mark where the edge of Mergui town stopped and a village of ‘long-leg’ shanties began. The foreshore was reclaimed in the late 1980s.

Behind Assumption Church are four of the last remaining gravestones in Myeik. Two belong to the D’Castros and one to a French priest. The fourth is considerably older and written in both Portuguese and archaic Thai. It is one of the only remnants of Siamese rule here.

Custody House

This building served as the jail for municipal offenders, and for prisoners awaiting trial next door or transfer to the larger Mergui Prison north of Mingalar Lake.

As of December 2016, the old Custody House was slated for demolition. This is unfortunate but understandable. Though historically important, it is a decrepit old building full of ghosts and bad memories for local people, and also occupies some of the most valuable real estate in the district.

The Mergui Seawall

Before the British constructed this barrier, the area from the waterfront to the hill was a tidal marsh where only rickety stilt-houses could be built.

Between 1923 and 1927, British engineers built the seawall and filled in the land with earth dredged from the sea channel and Mingalar Lake, which was only a brackish pool. They also removed earth from the low hills north of the lake despite opposition from landowners. The project ran far over budget due to equipment failures and heavy rains.

The seawall did not extend all the way to Naukle Quarter as it does now. Its southern limit was at the current Seik Nge jetty (previously Steamer Wharf), and old maps show that Assumption Church overlooked the tidelands from just across the road. The area south of the main pier thus continued to shelter Mokens and mangroves after Burma’s independence.

Today, middle-aged men can remember swimming in the sea there at high tide and playing under the stilts of ‘long-leg houses’ at low tide. The seawall was then extended and the land reclaimed. The mangroves disappeared for good; the Moken quietly disappeared deep into the Mergui Archipelago.

Mergui Hotel

At one time, this building was the premier accommodation in town. It is now the Mergui de Kitchen, which is fast becoming the best restaurant in town. The business may serve as very useful inspiration for Merguians wishing to profit from their valuable heritage. The building dates to the 1920s or early 30s, though it seems to have undergone a few additions over the years. It is well-preserved.

There is an almost-identical building next door, though it is a private residence. It was used as headquarters by the Japanese army during their occupation.