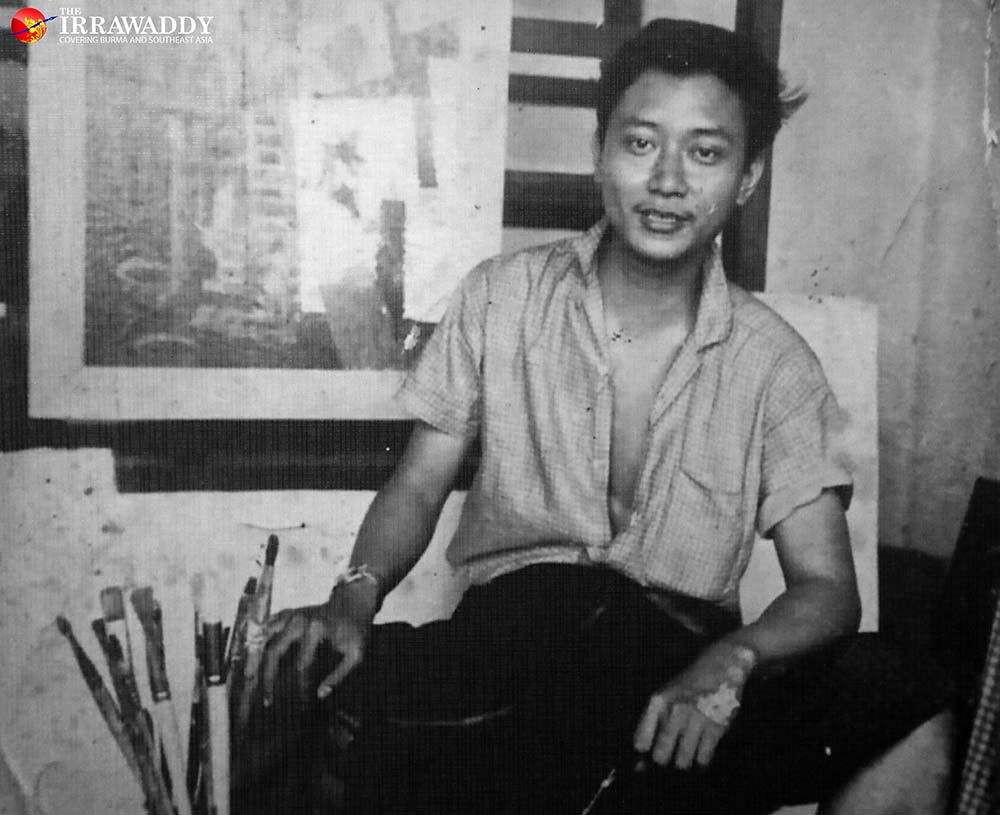

YANGON—When it comes to art, his interests seem boundless. No one in Myanmar would dispute the fact that he succeeds at whatever he turns his hand to. At 85, U Win Pe is acclaimed mostly for his paintings, writing and the films he has directed. In short, he is the very definition of the “multi-talented artist”.

But ask him which art form is his favorite and his answer may surprise you: “None”.

“I never seem to get hooked on any of them,” he adds.

This may sound like an absurdity from a man praised as a leader of the second generation of Myanmar’s modern art movement, and whose paintings are heavily sought after by admirers at home and abroad. Readers who have been enchanted by his short stories, teeming with allegory and metaphor, are bound to give him quizzical looks. Moviegoers who have been thrilled by his unique imagery and scripts in the 1970s and early 1980s will be left scratching their heads.

But if you press him to define his talent, one of Myanmar’s most celebrated living artists is likely to insist that he’s just a storyteller.

“I love to tell stories in the way that I understand them. That’s why I wrote and directed movies. You could say the same about painting in a way,” he said.

“I’m a jack of all trades, master of none,” he added.

Perhaps it’s this ability to work in so many different media, however, that has made U Win Pe who he is today—a man of many talents.

Culture Clashes

Born in 1936 in Mandalay and raised in a family passionate about the arts, young Win Pe was introduced to music and drawing by his father before he entered primary school. His father, Shwepyi U Ba Tin, a famous scholar on Myanmar art, history and culture, made sure that his five children were familiar with Maha Gita, Myanmar’s traditional classical music. When he wasn’t singing songs or playing on a traditional xylophone, little Win Pe made his father proud by drawing anything that came to his mind on a slate.

For all his devotion to traditional classical music, however, he was attracted to Western music, especially jazz and blues, from the age of around 10 years old in the years immediately after World War II. He was mesmerized by the music of Louis Armstrong, Harry James, Ella Fitzgerald and others to whom he was exposed through American musical films. At home, he secretly tuned to Radio Ceylon from Sri Lanka for European classical music, lest his anti-colonial nationalist father should become aware of his new passion. Apart from playing traditional xylophone at home, he learned to play trumpet and saxophone without his father’s knowledge.

“I have experienced ‘culture clashes’ since I was young, because I liked all of them,” he said.

When he learned about his son’s new musical tastes, Shwepyi U Ba Tin was shocked, at one point even asking him, “Do you really like it that much?” But he didn’t protest. Instead, he took Win Pe to a lawyer who studied musicology as a supplementary subject when he was abroad. Years later he thanked his dad for expanding his musical horizons and helping him to develop a deeper understanding of music that helped him learn the value of traditional Myanmar music.

His love for music has lasted to this day. In his home in a suburb of Yangon, a Yamaha electric piano stands in a corner of his studio. A Myanmar traditional xylophone sits next to a Western stringed instrument, symbolizing in a way the “culture clash” he experienced in his younger days. When the mood strikes, he will play a Maha Gita piece on the piano. “Due to tuning problems, I mostly play keyboards now,” he said.

Renaissance Man

On the art front, with his father’s encouragement of course, U Win Pe studied under U Ba Thet, a successful pre-war painter especially popular among colonial administrators, and U Kin Maung, a banker-turned-painter said to be the first artist to bring modernism and abstract expressionism to Myanmar, along with fellow young artist Paw Oo Thett, who would later achieve praise as a second-generation leader, like U Win Pe, of Myanmar’s modern art movement.

U Win Pe recalled that U Kin Maung’s approach to modern art was conceptual; he explored why and how a work was made the way it was. According to “Myanmar’s Second Line Leaders of Modern Art” by Ma Thanegi, the old master enlightened young Win Pe and Paw Oo Thett to the fact that creative thought is the main body within art, with different “-isms” branching out in all directions. The author notes that the two began to appreciate the sense behind the distortions and imbalances, as well as the use of non-natural colors, all of which expressed an idea rather than a life-like depiction of a subject.

“Only with the understanding of the concept will there be a period of creation, as well as periods of thinking freely and honestly. This can make your [modernist] creation more complete. That’s what I’m interested in,” U Win Pe explained.

Despite its relative popularity in Myanmar today, the modern art movement didn’t get off to a good start in the country. There was a huge gap between modernists and traditionalists in the early 1960s when U Win Pe and his fellow artists like Paw Oo Thett and Kin Maung Yin, another second-generation movement leader, devoted their time to modernism. In Socialist Myanmar at that time, any interest in Western culture was labeled “decadent” and modern art was denounced as “psychotic” art. But the trio were undeterred by such criticism. Rather than being insulted, U Win Pe said, they took it as if they had been “hit with flowers” and kept doing what they believed in to pave the way for, and inspire, generations of artists to come.

One of those inspired by them is Shwechihto Sein Myint, a Mandalay painter known for his fusion of modernism with characters drawn from traditional Myanmar folklore, like Nats (spirits) and Zawgyi (a mythical alchemist). The 75-year-old admitted that as a young artist he used to silently watch with admiration while U Win Pe was painting.

“Later I found myself in the modern art movement they paved the way for,” said the prominent third-generation artist.

In 1966, after a few years doing stints as a newspaper cartoonist and a gem dealer, U Win Pe was appointed principal of Mandalay’s State School of Fine Art, Music and Dance, a position he held so dear he decided at the time he would stick to it for the rest of his life. He was just 31 years old. The school’s nearly four dozen teaching staff were older than him, apart from an instructor in the traditional dance department.

But the young principal had visions of modernizing the playing of Maha Gita using standardized metering and rudiments like the counterpoint and syncopations found in Western music. He wanted to share modern concepts with art students while introducing modern ballet to choreography students.

However, it turned out to be a failed mission. As the promotion of art and culture had never been a big priority for the government—they were “disappointingly uninterested” as U Win Pe put it— there was little or no state funding for the school. Conservative and traditionalist teaching staff wondered aloud, “Is he destroying the school?” He left the position four years later.

“I had to leave the prestigious job early. I had a faint hope that some of [these goals] would be achieved during my absence, but nothing happened,” he said.

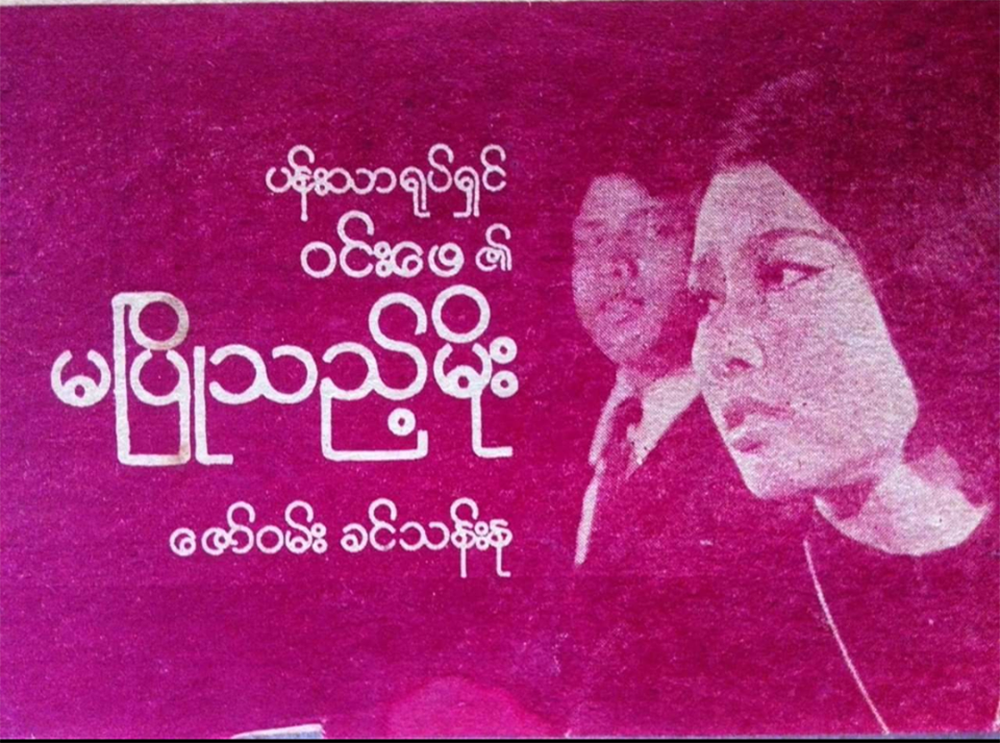

After leaving the school, U Win Pe spent the next two decades as a film director, short story writer and video movie maker. For him, he said, making movies was a melting pot of art encompassing audio, video, literature, drama and any others you could name. “A guy like me can’t resist that at all,” he said. His first movie, ‘Let Not the Sky Fall’, came out in 1973 to great acclaim. In 1981, he won Myanmar’s equivalent of the Academy Award for best director for another film.

“A film director has to be interested in many things, and you will become a very efficient story teller. I’m curious about everything but a master of none. That’s why I became a director,” he explained.

He was so happy with filming at the time—he directed more than 20 movies—that he barely did any painting, one of his old loves. He recalled that this annoyed his old friend Paw Oo Thett. His fellow artist finally challenged him: “Dude—have you given up painting for good?”

To his friend’s dismay, U Win Pe replied, “Yes, I have!”

It should have been some consolation to Paw Oo Thett when their mutual friend U Kin Maung Yin intervened in the argument by saying, “Don’t you know? He has been painting—with moving pictures.” But Paw Oo Thett didn’t seem very pleased, because U Kin Maung Yin was a movie buff and had directed a couple of movies himself.

U Win Pe’s exclusive devotion to directing films was curtailed right after the military coup in late 1988, when the Myanmar movie industry faced a shortage of film stock, which was imported from abroad.

So, the Renaissance man found a new outlet, turning his attention to writing. His reason was simple: to put food on the table for his family, including his five children.

“We were out of work at the time, as there was no film. So I painted and sold the works to foreigners. But it didn’t work. So I wrote,” U Win Pe recalled.

His short stories, with their explorations of human nature, were well received, so he churned out four or five short stories per month. When his friends warned him that he was being too prolific, he replied that he had no choice as he had to make a living.

Some critics have taken U Win Pe task for what they see as a tendency to switch his interest to wherever he can make more money—for example in painting.

He feels no shame in admitting there is some truth in this. “If they say I stopped writing for painting to earn more, I have to admit, shamefully, yes!” he said.

“Some people say they eat not for survival but for art’s sake. It sounds great, but for me, that was never the case. On the one hand, you have to appreciate yourself to be able to do art-related work for a living. I’m satisfied with what I’m doing,” he said.

In 1993, three short stories by U Win Pe appeared in the PEN American Center’s Freedom-to-Write Report, “Inked Over, Ripped Out”. Anna J. Allot, a former lecturer in Burmese Studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, who selected and translated seven Myanmar writers’ work, remarked that U Win Pe is “generally agreed to be one of Burma’s popular storytellers” and that his varied career has furnished him with a richness of experience that gives power and authenticity to his short stories: at the same time, she said, his artist’s eye enables him to paint a scene vividly in just a few lines.

In the report, she discussed the way that U Win Pe’s short stories may seem on first reading to be accounts of fairly unimportant events happening to ordinary folk. “The stories move rapidly, and often comically, at first; but the situation can change suddenly. What was simple becomes complicated, even violent, brutal, tragic, and above all unexpected. By the end of the story the reader may find himself wondering if there wasn’t perhaps a deeper meaning to the series of events described,” she said.

As it turned out, his short stories brought about in a major turn in his life. In 1994 he became the first person from Myanmar to be invited to join the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa. While participating at the program, his outspokenness about freedom of expression didn’t go unnoticed in Myanmar, and he was unable to return lest he was arrested. Staying in the U.S., he became involved in setting up Radio Free Asia’s Myanmar Service—from selecting the signature tune and insert music to writing news articles and others things—when it was planning to expand its coverage on Myanmar in 1996. He worked there as a senior editor from 1996 to 2005.

Daw Tin Htar Swe, one of U Win Pe’s RFA colleagues, remembers him as a humble man for all his fame as a painter, director and writer at the time. He used to complain, she said, about his weakness in news-related matters because he had no journalism background.

“But he did it. He was really good at political news analysis. If you asked him, it would be done in 20 minutes. The copy was very clean and precise,” the one-time RFA senior editor said.

“Despite his seniority, he never behaved like a know-it-all. Very patient and a good co-worker,” she added.

Man of Adaptability

U Win Pe left the U.S. for good in 2015 to settle back in Yangon. Now he lives in North Dagon with his family, spending most of his time painting. Ever the jazz music fan, he refers to his style of painting as “improvising in terms of colors and lines.” After some finishing touches, a combination of bold lines and a harmoniously placed riot of colors, frequently with human figures with no mouths, they emerge as things of beauty. At 85, he no longer writes or directs; he complained about a urinary problem and other minor health issues. (His fellow second-generation modern art leaders Paw Oo Thett and Kin Maung Yin have both passed away). When visitors—acquaintances and admirers—show up, he drops his brushes to entertain (with a few touches of humor) and enlighten them, still in his paint-stained clothes, on topics ranging from art to politics to culture.

Politically, U Win Pe was never a friend of the previous military governments, from the time they came to power in 1962. He openly criticized their mismanagement wherever he went, let alone with friends at teashops. While he was working as a cartoonist at the prominent left-wing Ludu Daily in Mandalay, the absurd brand of humor in his work attracted military scrutiny. He once drew a mermaid visiting a doctor, asking that her upper body be changed so that her full body was that of a fish. The men in uniform interpreted that to mean that, “People under the regime were suffering so much that they were tired of being humans.” The then military chief in Mandalay warned the paper’s editor, Ludu U Hla, not to publish cartoons with such “hidden meanings”.

“Politics was not on my mind when I drew that, but it couldn’t be helped that it turned out to have that kind of implication. I quit the job because if I kept drawing cartoons like that I would have been arrested,” he recalled.

But old habits die hard. When he joined the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa in 1994, he shared his views on his country’s dire situation outspokenly with his fellow participants from other countries. The then military government ordered his arrest upon his arrival back in Myanmar because, he later learned, he said bad things about Myanmar in the U.S.

“I just talked with [people there] as I would with friends in a teashop in Yangon. They [Military Intelligence] said it’s OK in Myanmar, but not in the U.S.,” he said. To avoid arrest, he had to stay in the U.S. until 2013.

He remarked that even today Myanmar is suffering from the consequences of military dictatorship in every sector of the country. He blamed the Ne Win regime’s nationalization of private businesses after 1962 for the serious decline in the country’s economy and for turning one of the most prosperous countries in Southeast Asia into the least developed one.

“Now we are still suffering the consequences of this ridiculous situation. Given my experience, even though there was fighting with insurgents in the 1950s, the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League government of the time managed to maintain a better economy,” he said.

Of his accomplishments in his various endeavors—from painting, writing and directing to journalism—the man of many talents would say that on a 100-1,000 scale, where 100 is least successful, he would be around a 400 or 500, meaning he commits himself to whatever he is doing.

“My writing peers recognized me as someone who could write. It’s the same in music, art, film and radio journalism. They said I’m not bad,” he said.

So, what’s the secret behind making everything he’s interested in happen?

“If I’m interested in something, mostly in the arts, I think seriously about what it is, about why and how it’s done. After learning the method, I just try it, but I’m not the master at what I am doing,” said the multi-talented artist.

Despite his claim not to have a favorite art form, he argued that there is one important thing that keeps him going: adaptability. As a believer in Buddhism, the celebrated artist quoted Buddha’s teaching that people need to be able to adapt to what they have, when and where they are. Otherwise, they will suffer.

“So, whatever art form I am working in is my favorite at that moment. Currently, I am in love with painting. I don’t do anything else. It was the same when I did film and the others,” he added.

For all his versatility and ability to work in many media—be it painting, writing, making movies, radio journalism or others—the one thing that remains at the center of his creations is storytelling. U Win Pe talks about things descriptively, as he sees them, whatever the medium. A good example that many people may be familiar with is his popular former weekly talk show on the BBC Burmese Service, “Win Pe’s Shoulder Bag”. The nearly six-minute-long show came about at the initiative of Daw Tin Htar Swe, then the Burmese Service head as well as a former RFA colleague of U Win Pe. From 2005 to 2014 he talked about his lifelong experience, politics, arts, culture—and even folk medicine for weeping eczema—in very engaging way and in a vivid narrative style that enchanted audiences from beginning to end. Each episode, by the time he signed off with “Good health to you folks. I’m Win Pe,” most listeners had usually learned something they didn’t know before.

Daw Tin Htar Swe said she was proud to have made the program happen, regarding it as one of her main accomplishments at the Burmese Service.

The veteran artist insists that storytelling is important in life because people are curious about things and need to be informed. To make that happen, he said, good storytellers are essential.

“We need someone who wants to tell people about something honestly in an explanatory way. Telling someone in such a way as to help them understand something is not easy—you basically need to be sincere and have a good intention—to let them know about something they don’t know or want to know,” he said.

So, is he a good storyteller?

U Win Pe offers a pragmatic answer. “If I wasn’t, people wouldn’t listen, or read my stories.”

Note: This story has been updated to correct the spellings of the names of author Ma Thanegi and artist Paw Oo Thett.