TOKYO—Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe recently pledged to promote more than 150 quality infrastructure projects in five nations in the Mekong River subregion—Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos—under a new blueprint, the Tokyo Strategy 2018 for Mekong-Japan Cooperation, which will be effective from 2019 to 2021.

Japan and China are competing for influence in Southeast Asia in order to secure supplies of cheap labor and agricultural commodities, as well as access to ideally situated ports and other strategic locations in the region. While Beijing seeks to extend mega-infrastructure projects into Myanmar under its Belt and Road Initiative, Japan touts the quality of its infrastructure while committing to follow through on completed projects by training local workers. Since the early 2000s, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) has supported the development of the Mekong Region, particularly regional connectivity, in terms of both industry and physical infrastructure such as roads, telecommunications and power transmission lines.

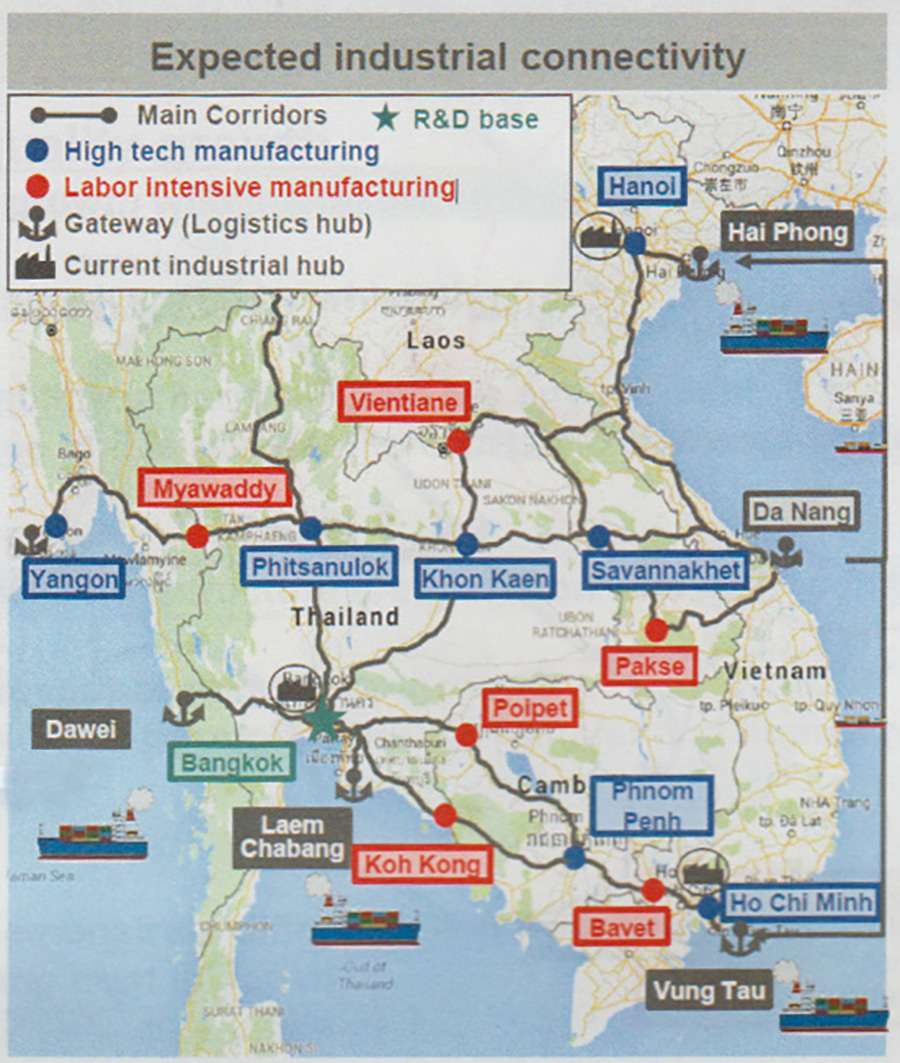

The Mekong Economic Corridor is an economic integration scheme comprising a network of land and sea infrastructure routes between the countries. Within this grand plan, Myanmar sits on two major economic corridors: the East-West Economic Corridor connecting Vietnam’s Dong Ha City with Yangon’s Thilawa Special Economic Zone (SEZ) via Cambodia and Thailand, and the Southern Economic Corridor connecting central Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand to the Dawei SEZ in southeastern Myanmar. Meanwhile, JICA plans to build a bridge in Mawlamyine as a part of the East-West Economic Corridor.

Prof. Manabu Fujimura of the College of Economics at Tokyo’s Aoyama Gakuin University is an expert on economic corridors in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) and has traveled along them, including in Myanmar. The Irrawaddy’s Nan Lwin spoke to Prof. Fujimura about Japan’s strategic connectivity plan in Myanmar, how this country can position itself between Beijing’s BRI and the Tokyo Strategy 2018, and related challenges.

Nan Lwin: What is the significance of Myanmar’s geographic location in relation to the GMS corridor?

Fujimura: Myanmar’s strategic importance has been quite obvious to observers in Asia. Myanmar is located right between China, Southeast Asia and South Asia. While China seeks to expand its economic sphere and Southeast Asian countries seek to explore new markets, Myanmar is best located to act as a conduit for their linkages with South Asia. Myanmar should leverage such expectations and opportunities and attract foreign direct investment that can support upgrading Myanmar’s economy, while at the same time avoiding the exploitation of its plentiful natural resources.

NL: What is Japan’s strategic connectivity plan for Myanmar?

Fujimura: In the short term of three to five years, the Japanese government and businesses would like to see a win-win outcome by assisting [the development of] much better connectivity between Bangkok and Yangon along the East-West Corridor, as many Japanese firms have bases around Bangkok and wish to extend their supply chains toward Yangon, including the Thilawa SEZ. In the medium term of five to 10 years, they wish to be part of the “bipolar development” [in the wording of Prof. Toshihiro Kudo of the National Graduate Institute of Policy Studies (GRIPS) in Tokyo] between Yangon and Mandalay, as reflected in the ongoing Japanese assistance to the upgrading of the railway between the two cities.

In the long term (10 years and beyond), they hope to secure a solid presence in the Dawei SEZ area through assisting ports and industrial zone development. Dawei is a natural extension from Bangkok where Japanese businesses have had first-mover advantages relative to other economic powerhouses in Asia. The main issues in developing the Dawei SEZ, however, would be the sheer financial burden of building infrastructure from scratch and the patience and insight required to foresee economic agglomeration to be formed over many years, also from scratch. How these issues can be overcome remains to be seen.

NL: Can Myanmar be a regional hub for GMS corridors?

Fujimura: Yes, I believe Myanmar will secure the position as a regional hub eventually, given its geographical advantages and the flexibility and resilience of Myanmar’s people, which I have been able to observe. But how long and what form it will take depend on many uncertain factors including the issue of the peace accord with armed ethnic minority groups and the handling of the Rohingya issue in relation to the international community, which may not understand well the subtlety of the country’s history.

NL: How do you see Myanmar’s future position between China’s BRI and Japan’s assistance via GMS economic corridors?

Fujimura: In terms of assistance to improve connectivity through economic corridors in the GMS, I understand that there has been a broad, but presumably not formally negotiated, mutual understanding between China and Japan: China goes ahead with advancing transport links that connect southern China with Laos and Cambodia, while Japan goes ahead with transport links that connect Thailand with Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam, respectively.

The Asian Development Bank, of which the two countries are among the top stakeholders, has acted as a mediator and a buffer between the national interests of the two countries. Very roughly speaking, “vertical” integration in the GMS has been driven by China while “horizontal” integration has been driven by Japan, with the other members of the GMS playing along and at the same time wisely avoiding pitching one power against another. Then Myanmar’s opening up to the Western world and joining the full picture of GMS cooperation in the 2010s may have triggered a new China-Japan rivalry in economic diplomacy.

The [most likely development] from the above picture would be that Chinese economic influence in Myanmar will continue to spill over from Muse [in Shan State on Myanmar’s border with China’s Yunnan province] to Mandalay and “upper Burma” in general, while Japanese and Thai economic influence will continue to spill over from Myawaddy [in Kayin State, on the border with Thailand’s Tak province] to Yangon and “lower Burma” in general.

NL: What are the major challenges for Myanmar in terms of integrating with GMS economies?

Fujimura: Well, as long as Myanmar sticks with the current outward-oriented economic management and makes continued efforts to improve the business environment such as through better infrastructure and the rule of law, foreign direct investment (FDI) will continue to flow in, helping to accelerate integration with neighboring economies and with the global economy. Absorbing technologies and know-how through FDI would be the best catch-up “shortcut” for Myanmar. Integration with neighboring economies in the GMS is a stepping-stone for Myanmar to further gain from linking with the global economy.

The main challenges in pursuing that course include [issues with] macroeconomic stability, as well as political stability. On the macroeconomic front, Myanmar needs to keep its fiscal situation including external debt under control so that it can control inflation as well as stabilize the value of its currency. Sustainable management of natural resources will also be important for Myanmar’s macroeconomic stability. I am not an expert on this, but Myanmar could learn from the past experiences of other ASEAN countries.

Myanmar looks surprisingly resilient in maintaining social stability in the middle of its transition toward an open economy and democracy. A key on both fronts would be to advance meritocracy, in which motivated and talented individuals, or technocrats in a narrow sense, who devote themselves to the good of the whole nation are deployed properly and rewarded fairly.

NL: The GMS is mainly focused on cross-border economic integration, so what are some possible negative impacts of the GMS corridor?

Fujimura: Proponents of the GMS economic corridors in both the public and private sectors—including myself, to be frank—tend to be those who are better positioned to analyze positive aggregate effects of regional integration using available quantitative data. On the other hand, visits to various specific borders in the GMS have enlightened me with many clues to potential harms that could arise from the easier movement of goods and people across borders (e.g., the excessive presence of casinos in border towns; induced illegal trade in natural resources and wild animals; and presumably induced illicit economic activities including trafficking of narcotics and people, etc.). The problem is that these negative effects are inherently difficult to identify precisely, let alone quantify, and therefore hard to weigh against the positive effects of economic corridors. Nonetheless, these negative aspects should be kept as transparent as possible and discussed openly in order to better inform the public.

(Prof. Fujimura’s comments do not reflect the views of the Japanese government or any Japanese organizations.)