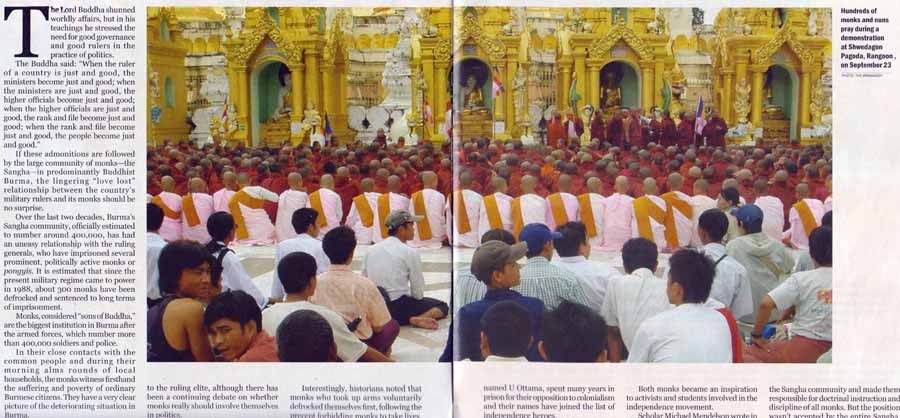

This month marks the 10th anniversary of the Saffron Revolution, a series of mass protests led by Buddhist monks against the military government.

Many social critics and political monks have long said the generals who kneel down before images of Buddha are the real threat to Buddhism and the Dhamma.

In this cover story first published in the October, 2007 print issue of The Irrawaddy magazine, founding editor-in-chief Aung Zaw explains why Myanmar’s generals fear the influence of the Sangha.

The Lord Buddha shunned worldly affairs, but in his teachings he stressed the need for good governance and good rulers in the practice of politics.

The Buddha said: “When the ruler of a country is just and good, the ministers become just and good; when the ministers are just and good, the higher officials become just and good; when the higher officials are just and good, the rank and file become just and good; when the rank and file become just and good, the people become just and good.”

If these admonitions are followed by the large community of monks—the Sangha—in predominantly Buddhist Burma, the lingering “love lost” relationship between the country’s military rulers and its monks should be no surprise.

Over the last two decades, Burma’s Sangha community, officially estimated to number around 400,000, has had an uneasy relationship with the ruling generals, who have imprisoned several prominent, politically active monks or pongyis. It is estimated that since the present military regime came to power in 1988, about 300 monks have been defrocked and sentenced to long terms of imprisonment.

Monks, considered “sons of Buddha,” are the biggest institution in Burma after the armed forces, which number more than 400,000 soldiers and police.

In their close contacts with the common people and during their morning alms rounds of local households, the monks witness firsthand the suffering and poverty of ordinary Burmese citizens. They have a very clear picture of the deteriorating situation in Burma.

More importantly, they probably have a better network, connections and influence than politically active students, who are constantly watched, imprisoned or forced into exile.

Who could imagine that these monks, living quietly in monasteries and studying Dhamma, would ever plan to rebel against the repressive regime? Yet history has shown that monks have long played a pivotal role in politics and that they would indeed dare such a bold and dangerous undertaking.

The role of political pongyis is controversial and potentially threatening to the ruling elite, although there has been a continuing debate on whether monks really should involve themselves in politics.

The Early Rebellion

Monks were involved in early outbreaks of resistance against British colonization, joining lay people in taking up arms against the British after seeing King Thibaw sent into exile.

Monks have their resistance martyrs—U Ottama, for instance, who led 3,000 rebels in the Salin area a year after the invasion of Mandalay. The rebel monk, also known as Bo Ottama, was captured and hanged by the British in 1889.

Interestingly, historians noted that monks who took up arms voluntarily defrocked themselves first, following the precept forbidding monks to take lives.

Another martyr, Saya San, who was an ex-monk, led a peasant uprising in Tharrawaddy opposing the tax system imposed by the British. Burma’s colonial masters sent 10,000 troops to quell the rebellion, capturing Saya San and sending him, too, to the gallows.

One of the top Burmese lawyers who defended Saya San at his trial was Dr. Ba Maw, who later became head of state in Burma’s Japanese-backed government.

Not all monks advocated armed struggle. Two who preached nonviolent resistance, U Wisara and another monk named U Ottama, spent many years in prison for their opposition to colonialism and their names have joined the list of independence heroes.

U Ottama, a globe-trotting, well-respected monk from Arakan State, was a powerful speaker whose calls for independence were featured in the national newspaper Thuriya. He once famously told the British Governor Sir Reginald Craddock to go home to Britain, in a speech that landed him in prison.

Like U Ottama, U Wisara was imprisoned several times for his public speeches and died in jail in 1929 after 166 days of a hunger strike. His prison sentences included terms of hard labor, and he was also defrocked.

Both monks became an inspiration to activists and students involved in the independence movement.

Scholar Michael Mendelson wrote in his “Sangha and State in Burma,” that all politically active monks tended to be labeled by the colonial authorities as “political agitators in the yellow robes.” Interestingly, a similar term is used by Burma’s current leaders to describe protesting monks.

Historians wrote that the British authorities were surprised to learn the influential role of the Sangha community, and soon after the invasion of 1885 they abolished the position of “Supreme Patriarch,” or Thathana-baing.

In former times, Burmese kings appointed Thathana-baing to govern the Sangha community and made them responsible for doctrinal instruction and discipline of all monks. But the position wasn’t accepted by the entire Sangha. The progressive Shwegin sect was one group that rejected it. Sectarianism created controversy and bitter rivalry among monks.

During the Kon-Baung period in the 18th century, conflicts arose within the Sangha over how the monastic robes were supposed to be worn, and two conflicting sects arose—the so-called Ton Gaing and Yon Gaing.

The Burmese scholar Tin Maung Maung Than records that the Toun-goo and early Kon-Baung dynasties were drawn into the rivalry by their royal patronage of one party or the other. In 1782, King Bodawphaya intervened in the controversy by siding with Ton Gaing.

One experienced colonial political officer, Col Edward Sladen, conversant with the power of the Sangha, advised British authorities to maintain the Thathana-baingsystem in order to head off conflicts in governing the predominately Buddhist country.

The role of Thathana-baing was undoubtedly a complicated one, involving a direct link between the monarchy and the Sangha. The Thathana-baing wielded influence and could even intervene in state affairs. One respected abbot even persuaded King Mindon to abandon corvée labor for his irrigation projects. It’s ironic that the current regime argues that forced labor is a feature of Burmese tradition and a means of making merit.

After independence, however, the influence of Buddhism and the Sangha went into decline, except for a period under the late prime minister U Nu, a devout Buddhist.

U Nu himself was ordained as a monk several times and rarely exploited Buddhism for his own political ends. Under his government, the Sixth Great Buddhist World Council was held in 1954, and he also created the Buddha Sasana Council.

Tin Maung Maung Than noted in his book, “Sangha Reforms and Renewal of Sasana in Myanmar: Historical trends and Contemporary Practice”: “Because of various Gaing and sectarianism U Nu failed to take effective reforms in spite of institutionalization of Buddhism within the state superstructure and notwithstanding the holding of the Sixth Buddhist Synod in 1954.”

U Nu also attempted to legalize Buddhism as the state religion in 1961. The attempt was considered to be a misguided policy, and it anyway failed to materialize as U Nu was ousted by Gen Ne Win one year later.

Ne Win regarded monks as a potential opposition and he developed a different strategy to control them. In the mid-1960s, his regime called a Sangha conference to issue monks with identification cards. Young monks and abbots stayed away from the gathering.

It wasn’t until 1980 that Ne Win succeeded in containing the monks by establishing a “State Sangha Nayaka Committee,” after a carefully orchestrated campaign to discredit the Sangha. Part of the campaign was to discredit a famous monk, Thein Phyu Sayadaw, who was accused of romantic involvement with a woman. He was defrocked.

Before the campaign, intelligence officers and informants of the government infiltrated the temples as monks and gathered information about monks and abbots.

Some well-known abbots, including Mahasi Sayadaw, an internationally respected monk who was invited by U Nu in 1947 to teach Vipassana meditation, were also targeted in the campaign.

Anthropologist Gustaaf Houtmann wrote in his paper “Mental Culture in Burmese Crisis Politics” that the regime had “distributed leaflets accusing Mahasi of talking with the nat spirits, and it was claimed that the Tipitaka Mingun Sayadaw, Burma’s top Buddhist scholar, had been involved in some unsavory incident two years after entering the monkhood.” Both monks were victims of their refusal to cooperate with the regime.

A number of scholars and historians noted, however, that some abbots accused and charged by the government were indeed involved in scandals and had romantic relationship with women or nuns.

The regime’s campaign sometimes took bizarre forms. Rumors were circulated, for instance, suggesting that one Rangoon monk, U Laba, was a cannibal. Several famous abbots were implicated in scandals and were either defrocked or fled to neighboring Thailand. Ne Win successfully launched a “Sangha reform”—also known as “Cleaning Up the Sangha.”

The government managed to get some recognition from elderly Buddhists by forming the Sangha Committee. But Ne Win did not pretend to be a devout Buddhist. He rarely participated in Sangha meetings and held few religious ceremonies during the 26 years of his rule. Unlike current leaders, he was rarely seen with monks.

During the 1988 uprising, however, his government asked the Sangha Committee to help restore order, and senior monks appeared in live television broadcasts appealing to the public for calm.

In August, 1988, days after the massacre in Rangoon, monks expressed sorrow for the loss of life, but—to the surprise of many—they also appealed to the regime to govern in accordance with the 10 duties prescribed for rulers of the people. The appeal failed to calm the public mood, but the message did remind many Burmese of the “10 duties of rulers”—the monks were telling Ne Win to be a good ruler.

On August 30, the Working People’s Daily reported: “1,500 members of the Sangha marched in procession through the Rangoon streets and gathered in front of the Rangoon General Hospital emergency ward, where they recited “Metta Sutta” in memory of rahans [monks], workers and students who fell in the struggle for democracy.” Many young monks were among the demonstrators.

For many Burmese, the struggle for democracy is not yet over and the discord between the Sangha and the ruling generals remains strong.

Unlike Ne Win and U Nu, the generals who came to power in 1988 openly and audaciously schemed to buy off the Sangha community. They have also claimed to be protectors of the Sangha, although their motive is to gain political legitimacy.

Aside from holding numerous merit-making ceremonies, offering hsoon and valuable gifts to monks, the military leaders are launching well-publicized pagoda restoration projects throughout Burma. Nevertheless, confrontations between rebellious monks and the authorities continue.

In Mandalay in 1990, troops fired on the crowds, killing several people, including monks. Angered by the military’s brutality, Mandalay monks began a patta ni kozana kan, refusing to accept alms from members of the armed forces and their families.

The same action has now been taken by monks in several provinces after authorities beat protesting monks in Pakokka, central Burma.

“Patta ni kozana kan” can be called in response to any one of eight offences, including vilifying or making insidious comparisons between monks, inciting dissension among monks or defaming Buddha, the Dhamma or the Sangha.

A “patta ni kozana kan” campaign can be called off if the offended monks receive what they accept as a proper apology from the individuals or authorities involved. This procedure involves a ceremony held by at least four monks inside the Buddhist ordination hall, at which the boycott would be canceled.

Some monks in Burma may believe that the “patta ni kozana kan” of 1990 is still in effect, since they haven’t yet received any proper apology—only a harsh crackdown. At that time, monks refused to attend religious ceremonies held by military officials and family members.

In one incident, the Mandalay Division commander at the time, Maj-Gen Tun Kyi, who later became trade minister, invited senior monks and abbots to attend a religious ceremony but no one showed up. Military leaders realized the seriousness of the boycott and decided to launch a crackdown.

In Mandalay alone, more than 130 monasteries were raided and monks were defrocked and imprisoned. As many as 300 monks nationwide were defrocked and arrested.

Former political prisoners recalled that monks who shared prison quarters with them continued to practice their faith despite being forced to wear prison uniforms and being officially stripped of their membership of the Sangha.

Several monks, including the highly respected Thu Mingala, a Buddhist literature laureate, and at least eight other respected senior abbots, were arrested. Thu Mingala was sentenced to eight years imprisonment.

Apart from being stripped of their robes, imprisoned monks in Mandalay were forced to wear white prison uniforms and were taunted with nicknames instead of being addressed with their true titles, according to former political prisoners.

One year later, in 1991, the then head of the military junta, Snr-Gen Saw Maung, suffered a nervous breakdown and retired for health reasons. Buddhist Burmese still say this was punishment for his maltreatment of the monks.

The 1990 crackdown divided the Sangha community. The late Mingun Sayadaw, who was secretary of the State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee, was ridiculed by young monks for not supporting the boycott campaign. He was at one time called “senior general Mingun Sayadaw,” and when he visited one temple in Mandalay young monks reportedly saluted him.

Today, while rebellious monks are prepared to go to prison, many senior monks and abbots are allowing themselves to become government tools by accepting gifts and large donations from the generals. By cuddling up to the ruling generals, these elderly abbots can no longer speak for the Sangha community at large, let alone comment on the suffering of the Burmese people. The divisions between abbots and young monks have inevitably widened.

The generals, on the other hand, won’t give up easily. In one spectacular bid to win the hearts and minds of the people, they borrowed a Buddha tooth relic from China and toured the country with it and also held a World Buddhist Summit.

In 1999, military leaders renovated Shwedagon Pagoda, after the Htidaw, the sacred umbrella, had been removed amid reports of minor local earthquakes. Local people said the spirits of Shwedagon had been upset with the removal of the Htidaw. Restoration of the pagoda complex did nothing to help the generals’ image, though.

The generals have also applied “divide and rule” strategies in dealing with the Sangha community and the opposition.

In 1996, the regime accused the National League for Democracy of infiltrating the Sangha with the aim of committing subversive acts against the authorities. The generals obviously did not want to see opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi developing too close a relationship with the monks.

In an attempt to neutralize the political role of Suu Kyi, the government sent a famous, London-based monk, Dr. Rewatta Dhamma, to visit the detained opposition leader in 1995. Claiming to be a peace-broker between Suu Kyi and the generals, the monk shuttled between her and top leaders. But his mission failed and he returned to London. Skeptics believe the generals had merely used U Rewatta in a bid to persuade Suu Kyi to relinquish politics.

Ironically, the regime leaders publicly accused Suu Kyi of being a communist and of sacrilege because she had said in a campaign speech that “any human being can become a Buddha in this life.”

Soon after her release from her first term of house arrest in 1995, Suu Kyi immediately traveled to Karen State, followed by infuriated intelligence officers. She went there to make an offering to “Thamanya Sayadaw.”

Traditionally, temples have provided hiding places for activists, and in 1988 monks offered shelter to fugitives from the intelligence authorities.

At one time, the regime even placed restrictions on opposition members, preventing them from ordaining as monks. Like universities and schools, politically active monasteries are under heavy surveillance.

The widely respected abbot Bhaddanta Vinaya, known as Thamanya Sayadaw because he lived on Thamanya Hill, was involved in projects to help villagers in the area, work that was shunned by the generals.

He was revered not only for the mystical powers he was said to possess, but also because of his refusal to kowtow to the regime leaders. He once famously refused to accept the gift of a luxury vehicle from the then powerful intelligence chief Gen Khin Nyunt.

Khin Nyunt could not buy Thamanya.

It may indeed be wrong to assume that Burma’s regime leaders are devout Buddhists. The generals and their families seem to place more trust in astrology and numerology than in Buddhist ritual. They treasure white elephants and lucky charms and are constantly seeking advice from astrologers.

Birds of a feather, such as the generals and their chief astrologers, not only flock together but fall together, too. Ne Win’s family astrologer, Aung Pwint Khaung, was arrested in 2002 when the former dictator and his family were charged with high treason.

Khin Nyunt’s chief astrologer, Bodaw Than Hla, was imprisoned after the former Prime Minister and Military Intelligence chief was toppled in 2004.

Many Burmese may find it hard to believe that their military leaders are actually preserving Buddhism. Even when they are building pagodas and erecting Buddha images, the projects are based on astrological predictions and readings.

Who, for instance, advised Ne Win to ride a wooden horse on his aircraft and to ask the pilot to circle his birthplace nine times? Who advised him to issue banknotes in denominations of 45 and 90 kyat?

Who advised Khin Nyunt to dress up in women’s clothing, complete with the signature flower that Suu Kyi wears, in order to steal power from “the Lady”? Who told Than Shwe to move his capital to central Burma?

It certainly wasn’t a belief in Buddhist tenets. Nor does Buddhism permit the military to beat, defrock, imprison and kill monks.

The decline of Buddhism and the rise of militarism in Burma are a source of concern for the people of Burma. Thus, it is no surprise to hear social critics and political pongyismaintain that the generals who kneel down before images of Buddha are the real threat to Buddhism and Dhamma.