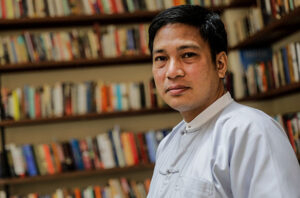

As a long-time native of Yangon, U Maw Lin has witnessed many changes in the former capital city.

He grew up in a flat overlooking the Sule Pagoda, in the heart of downtown, and as a child played football in Maha Bandoola Park just across the road.

From there, he and his friends would walk west, to China Town, for a bowl of noodles. For a cup of tea, they would stroll east on spacious pavements. These were some of the most memorable experiences of his youth.

But those days now seem a distant memory for the 56-year-old Yangon-based architect, who said that lax regulations on urban planning were threatening his native town, particularly since political and economic reforms in Myanmar since 2011.

“I can no longer imagine those kinds of walks these days, as the city has changed a lot,” he said. “Yangon today is suffocating.”

Outside his downtown office, the wide pavements that Yangon was once famous for have shrunk by two-thirds to make way for the growing number of cars on the now traffic-clogged streets. Drivers too are complaining as commute times have dramatically increased.

A few minutes’ drive away, large public spaces that were once venues for public events and entertainment are disappearing in the name of modern development.

In some townships, more than 1,000 people live per hectare—a number almost double that of Dhaka in Bangladesh, one of the most densely populated cities in the world, where an average of 555 people live per hectare.

“If problems like these are not tackled now… they will become very difficult to fix,” U Maw Lin warned.

Mounting Concerns

In January, an international forum on the role of heritage in sustainable development was held in Yangon in response to the challenges facing Myanmar’s largest city.

At the forum, experts pointed out that interest in heritage conservation had not yet translated into government policy. A lack of coordination among the relevant government agencies and an absence of guidelines across the board—from building safety to zoning, land use, urban design and planning—were among the concerns raised.

The forum followed close on the heels of an open letter sent by a group of urban experts, including U Maw Lin, to President U Thein Sein requesting “urgent action” to rein in unruly urbanization projects and address the lack of “systematic urban planning controls” for the city.

To enforce the controls, the experts urged the president to enact the Myanmar National Building Code and Zoning Plan to ensure building safety and regulate proper restrictions on land use and building heights for developments. Both laws have existed in draft form for more than a year.

Dr. U Kyaw Lat, an advisor to Yangon City Development Committee (YCDC)’s Urban Development Affairs department, said laws and regulations to control building density were of paramount importance and called for increased public participation.

“Even though I work with YCDC, they can reject what I suggest if they are not happy with it,” he said. “Yangon Region’s chief minister is above the YCDC and he decides everything. So far, the Zoning Plan has still not been recognized by the Yangon government.”

The failure to enact urban planning legislation has undermined efforts to protect the city’s heritage and created uncertainties over building controls.

The most prominent example is an international development project in the shadow of the Shwedagon Pagoda. Although buildings within a one-mile radius of the revered pagoda are supposed to be restricted to a height of 62 feet, the government reportedly approved a project proposal that included building heights above this restriction.

“I can’t think of anything more important to heritage conservation in Yangon than the protection of the Shwedagon and views of the Shwedagon,” said U Thant Myint-U, the founder of Yangon Heritage Trust (YHT), an NGO trying to protect Yangon’s architectural heritage and lobbying for policies on heritage conservation.

“The area can very soon, without a doubt, be listed as a World Heritage Site. The proper development of the Shwedagon area can help bring billions of tourist dollars in the future. Inappropriate development will jeopardize all this,” he said.

Calls for Action

Established in 2012, YHT has intervened to stop demolitions of pre-1960 buildings in the downtown area and campaigned to stop other inappropriate new developments. At the request of the government, YHT drafted a law on urban conservation in 2013 that would help protect the city’s heritage.

Two years later, the law remains in the draft stage, and U Thant Myint-U said the government was now having to make decisions on an ad-hoc basis.

“I’m sure there are many competing interests at stake. But I think a clear regulatory framework would be best for business as well as for conservation, as it would make clear exactly what is allowed and the processes to be followed,” he said.

U Toe Aung, director of the YCDC’s Urban Planning Division, defended the time taken to implement draft legislation. He said the need to seek the opinions of different stakeholders had led to delays in enacting the zoning law.

“A law should be consistent with the existing legal framework. To make it strong, you have to review it from every angle. If it is one-sided, it will not be OK,” he said.

Aside from urban conservation and heritage protection, an overhaul of the city’s ageing infrastructure is also urgently needed.

“Everything here needs to be rehabilitated; the water supply system, the road network and so on. Pipes are dilapidated. All the water pipes have to be changed,” said Suzuki Masahiko, an advisor on the Japan International Cooperation Agency’s Greater Yangon Strategic Urban Development Plan, a master plan for infrastructure projects needed to make Yangon more livable by 2040.

Mr. Suzuki said that, to date, the Myanmar government had followed less than 10 percent of the master plan JICA provided in 2013. The plan recommended initiatives such as a water supply project, pilot projects on a traffic signal system and a proposed Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system.

The government’s focus on achieving certain short-term results is a concern.

“They asked us to submit a detailed BRT design and start construction within one year,” Mr. Suzuki said. “That’s absolutely impossible for us, [considering] funding, design and construction.”

The Yangon Region government has attempted to tackle issues such as traffic congestion with piecemeal solutions, such as placing concrete blocks on roads to segregate buses from private vehicles. The results so far have been poor.

“The election will be held at the end of the year and the central and regional governments are in a hurry to do something in response to the people’s demands,” Mr. Suzuki said.

Yangon’s challenges are many, and no one believes the task ahead is easy or should be inappropriately rushed. But on some issues, it seems clear that hurry is now needed. The delay in enacting zoning legislation is placing the city’s priceless assets in real jeopardy.

One of Asia’s great historical cities has every potential to be even greater for residents, visitors and commercial activities alike in the future. It can also lose out and become just another choking metropolis. Which will it be?

This article originally appeared in the Mar. 2015 issue of The Irrawaddy Magazine.