YANGON — The seventh edition of Myanmar’s pioneering Wathann Film Festival showcasing independent cinema wrapped up on Monday.

The festival jury presented five awards from nearly 30 competing films. The Best Documentary Award was most remarkable, however, as the winning film had not actually been shown at the festival.

The 21-minute documentary “A Simple Love Story” directed by Hnin Pa Pa Soe tells a love story between a transgender woman and a transgender man, challenging norms surrounding gender identity and love.

The decision not to show the film was, in the end, the director’s choice. Myanmar’s censorship board advised that the closing line of the film be re-edited for public screening at the festival.

But the director wanted the film to be shown as she created it and refused to modify it.

Cinematic Freedom

The film censorship board is chaired by the director-general of the Ministry of Information’s Motion Picture Development Branch (MPDB) and is made up of more than a dozen representatives from different organizations including the Myanmar Motion Picture Organization (MMPO), the Myanmar Music Association, the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture, the Attorney General’s Office and the military-controlled Ministry of Home Affairs.

The regulations that were used to scrutinize the content of movies cover multiple principles, ranging from politics, religion, culture and goodwill among ethnicities.

The ending line in the film that made the censorship board unhappy was a question which asks, “Does love have man, woman, tomboy and shemale?” However, the film remained in the festival’s competition section and was also reviewed by the jury even though there was no public screening.

The film festival organized a panel discussion about freedom of expression with director Hnin Pa Pa Soe, program director Hla Myat Tun of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights organization Colors Rainbow and writer Han San on Saturday in lieu of the screening of the short documentary.

Thaid dhi, co-founder of the Wathann Film Festival who moderated Saturday’s panel discussion, stressed that Myanmar’s 1996 Motion Picture Law, which grants authority to the censorship board to scrutinize films, needs urgent reform to be in line with democratic norms supporting cinematic freedom.

“The country is heading towards a democratic path but this legislation restricts [filmmakers] with undemocratic provisions,” Thaid Dhi said.

Tackling Discrimination Presented in Everyday Movies

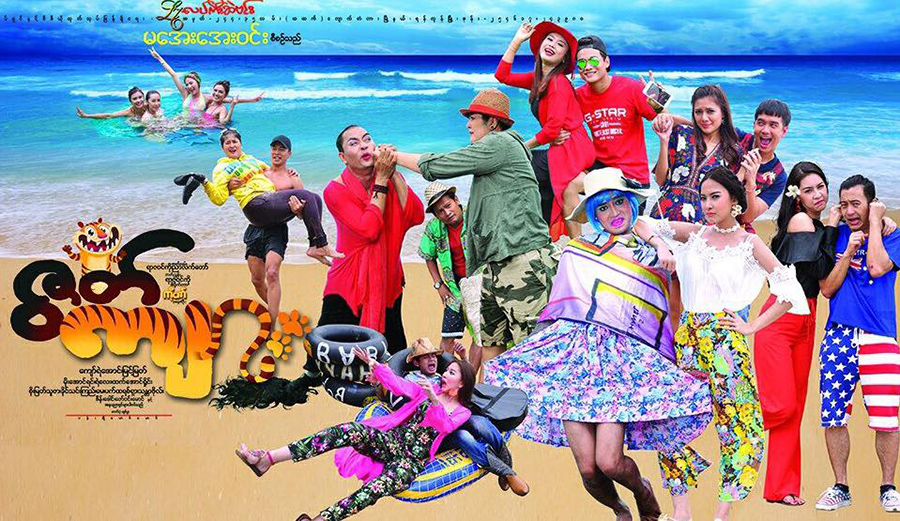

Referring to mainstream Myanmar films that portray transgender and homosexual characters as wacky, flamboyantly-dressed stereotypes, Hla Myat Tun highlighted that films at box offices mischaracterize the lives of the LGBT community in Myanmar society.

During the discussion, he also questioned the accountability of the censorship board and why it would repress a short film that sheds light on human dignity and tells a real story of actual people but allow hour-long fictionalized movies that mock, discriminate and damage the dignity of the LGBT community—especially transgender women—to be shown at cinemas.

“Such a film doesn’t insult anybody or harm any individual’s rights, but rather promotes [gender] identity,” Hla Myat Tun said.

“We are accountable for the films we produce. I question if the censorship board holds the same accountability for tens of thousands of movies they have allowed to be screened,” he asked.

Even though the audience did not have a chance to watch the film, the jury members mentioned at the awards ceremony on Monday that choosing her film as the best documentary was not for political reasons but it was simply the best film in their view.

“With well-composed images and well-balanced rhythm, the filmmaker explores the depths of love beyond gender conventions and social boundaries,” said jury member Marc Eberle, who teaches documentary filmmaking at the Goethe Institute in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, when he announced the prize on stage.

The storytelling managed to surprise the audience and communicated great intimacy in portraying what it means to love oneself and another, he added.

Shift to Rating System

Besides the award-winning documentary film, the censorship board also put pressure on organizers of the film festival by claiming scenes from regional and international films that include nudity and sexual activities such as masturbation and lovemaking were not suitable to be shown to the public.

Festival organizers had to manually block the scenes in front of the movie projector throughout the six-day festival.

Filmmakers and audiences who came to the festival said they felt bothered and annoyed to watch movies that had been tempered by censorship at the film festival.

Lamin Oo, a producer at Tagu Films Production, said it was disrespectful to filmmakers who have worked very hard to make the films and also ruined the audience’s experience.

Lamin Oo explained that sexual content is something that Myanmar censors always interfere with and often give two explanations—that sexual content is inappropriate for some audiences and that sexual content does not fit with Myanmar culture.

“I think the latter explanation is ridiculous,” he told The Irrawaddy.

“We are all sexual beings and filmmakers have every right to explore that part of the human experience in their work,” he stressed.

He agreed, however, that some sexual content isn’t suitable for audiences of all ages and it can easily be solved with a rating system instead of blocking the screen or censoring subtitles or censoring sound—all of which he encountered at this year’s Wathann Film Festival, he said.

Lawmaker Daw Phyu Phyu Thinn, a member of the parliamentary committee drafting a new version of the Film Law, told The Irrawaddy on Wednesday that the bill is now nearly complete and it will be submitted to parliament this month after consulting with film industry experts.

She said that the new legislation would constitute a rating system based on age of the audience, instead of censoring content, and creating a government council to regulate the industry.

Filmmakers have stressed that the censorship board’s regulations and principles can become a potential threat for freedom of artistic expression and those who have long worked under the country’s strict censorship practices cannot help but continue to self-censor while making films.

However, the country’s rebellious and enthusiastic young filmmakers, like Hnin Pa Pa Soe, are determined to resist censorship.

“I won’t let self-censorship hinder my future works and will continue creating films that the LGBT community can always be proud of,” she said.