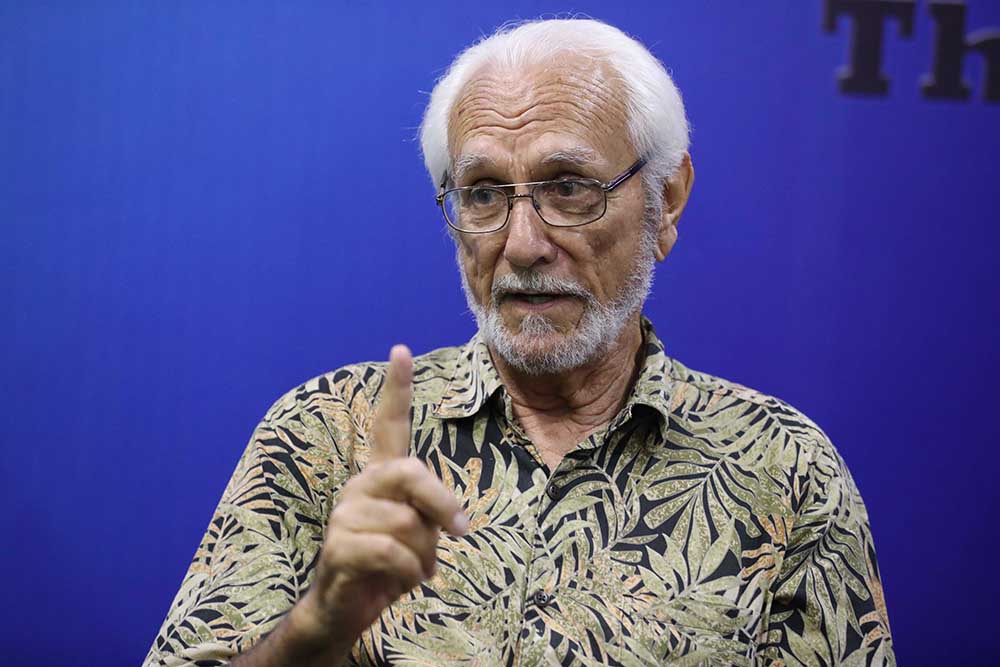

YANGON—American sculptor Jim McNalis still remembers the moment he was thrown into the street by security guards at the Myanmar Embassy in Bangkok after a staffer behind the counter rejected his visa application.

It was 2006. The trip he had planned was not his first; he had been visiting the country since 1998.

This time, however, the embassy official snapped, “No visa!” When the sculptor asked him why, the man behind the counter said simply, “Problem!”

Before he had time to realize that he had been blacklisted by the military regime, McNalis was escorted out into the street by security guards.

“I didn’t expect that kind of friendly welcome,” he jokingly recalled 12 years later. The reason for the visa denial was a very unflattering caricature sculpture McNalis had made of Myanmar’s then junta supremo Senior General Than Shwe.

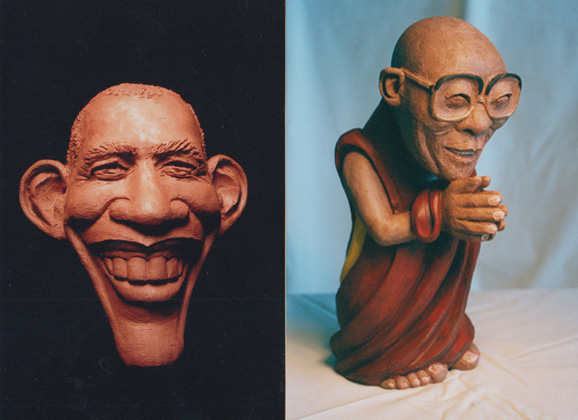

The 77-year-old American artist has long been an advocate of Myanmar’s democracy movement. Among the movement’s supporters outside the country he is best known for his sculpture series “Democracy Heroes of Burma”, which features personalities like Daw Aung San Suu Kyi; veteran journalist and democracy activist U Win Tin; Dr. Cynthia Maung, director of the Mae Tao Clinic on the Thai-Myanmar border; and student leader Min Ko Naing. At the same time, he has developed a reputation as a caricaturist, creating sculptures that ridicule dictators like Snr-Gen Than Shwe and North Korea’s Kim Jong Il.

He first became interested in Myanmar in 1989 when he stumbled into a refugee camp in Mae Hong Son near the Thai-Myanmar border. He was amazed by what he witnessed there and has been interested in Myanmar issues ever since.

It wasn’t until he visited the country for the first time in 1998 that he realized how awful the regime was and how it impacted people’s lives. When he first saw Snr-Gen Than Shwe’s picture, the sculptor recognized in his features what he describes as the arrogance all dictators have: The belief that, “This is my country. I’ll do what I want with it.”

“The last thing they’d ever experience is humiliation or being ridiculed. That’s where I came in,” he said.

McNalis started working on his caricature of the then dictator in around 2000 or 2001. He believes that caricature has the power to grab people’s attention.

“And then if you can invest humor in it, they will carry it away with them,” he added.

As it turned out, however, his subject failed to see the beauty, or get much joy, from McNalis’s creations.

One portrayed Snr-Gen Than Shwe as a pig wearing a cap emblazoned with an SS-like skull. The other showed him as a horned figure clad in a uniform festooned with a chest full of medals engraved with initials like B, C, E and M. (As McNalis explains, that’s B for Brutality, C for Consigned and Child Labor, E for Evils yet to be committed and M for Murder.) To complete the image, the dictator sports cloven hooves and a tail. The title of the work is “Than Satan”.

“All that tells the story. If you turn it around, you see he holds a blade behind his back. You know… it’s deceitful,” he explained.

When the sculptures were complete, he took pictures of them and emailed them to the military, government agencies and major businesses run by military cronies in Myanmar. The pictures appeared in The Irrawaddy Magazine in the early 2000s and were then secretly reprinted elsewhere in Myanmar, and also appeared in the U.S. and in Europe, calling attention to the bigger story behind the caricatures. This was too much for the military regime, which banned McNalis from the country.

“Most people think caricatures are cartoons for children. [But] it’s really powerful and it can get you blacklisted by a country,” he said.

The “Democracy Heroes of Burma” series began with a sculpture of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. He started it in 1998 after his first trip to the country because he found her interesting and inspiring as an imprisoned woman facing down a most brutal military dictatorship.

“That’s worth investing all my time and talent, to see if I can capture her [likeness] and make it a benefit to her and Burma and anybody else. That’s what I had in mind and heart what I was doing that,” he recalled, using the country’s former name. McNalis got the chance to meet Daw Aung San Suu Kyi in person in 2011, and had the honor of installing his bust of her in the living room of her Yangon home the following year.

The “Democracy Heroes of Burma” sculptures are occasionally put on display outside Myanmar, and McNalis uses them as a way to educate people about the country. When people come into his studio in Florida to see Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s sculpture, they ask about her.

“Then I get to tell them about her and Burma, rather than getting out and saying, ‘You’ve got to listen to me! This is important!’” he said.

McNalis sees all the dictators and democracy heroes he has sculpted and caricatured—from Myanmar and elsewhere, including North Korea and Russia—as illustrations of good and evil.

“Oil and water are completely different, but the common denominator is power and the impact they have,” he explained.

“I can’t imagine what goes through somebody like Than Shwe or somebody hideous. They have no empathy for you and your family. And it’s just amazing how [another person] can make us better than we are, like…Daw Aung San Suu Kyi…the Dalai Lama… By being exposed to them and how they think, you have improved as a person,” he explained.

McNalis has just finished a book, “Nobility of the Human Spirit”, about his discovery of who Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is, what inspired him to make that sculpture and the impact it had on him, and his meeting with her.

When it comes to the international criticism she is now facing for failing to use her moral authority to speak out about the Rohingya issue, he said he feels a great sympathy for the position she is in today, as people outside don’t have a deep understanding of Myanmar.

Currently, the military-drafted Constitution gives armed forces members control of key ministries and a quarter of the seats in Parliament.

“The outside world thinks [Myanmar has] a civilian government [that is] democratically elected, [and that] Suu Kyi is in charge… You know, it’s basically a military regime!” he said.