For artist Khit Bhone Mo, death could be beautifully gift wrapped to give as a wedding present. Or it could be commanded to greet everyone with grace as they enter the office of a CEO in a bookstore. Sometimes, no matter how tight its schedule, death just had to sit all day long by the cobwebbed window of his tiny gallery when the artist summoned it to be there.

“This painting is inauspicious to be in an office,” remarked a monk when he saw Khit Bhone Mo’s conventional Buddhist painting—complete with an unnerving twist—in San Mon Aung’s office one day.

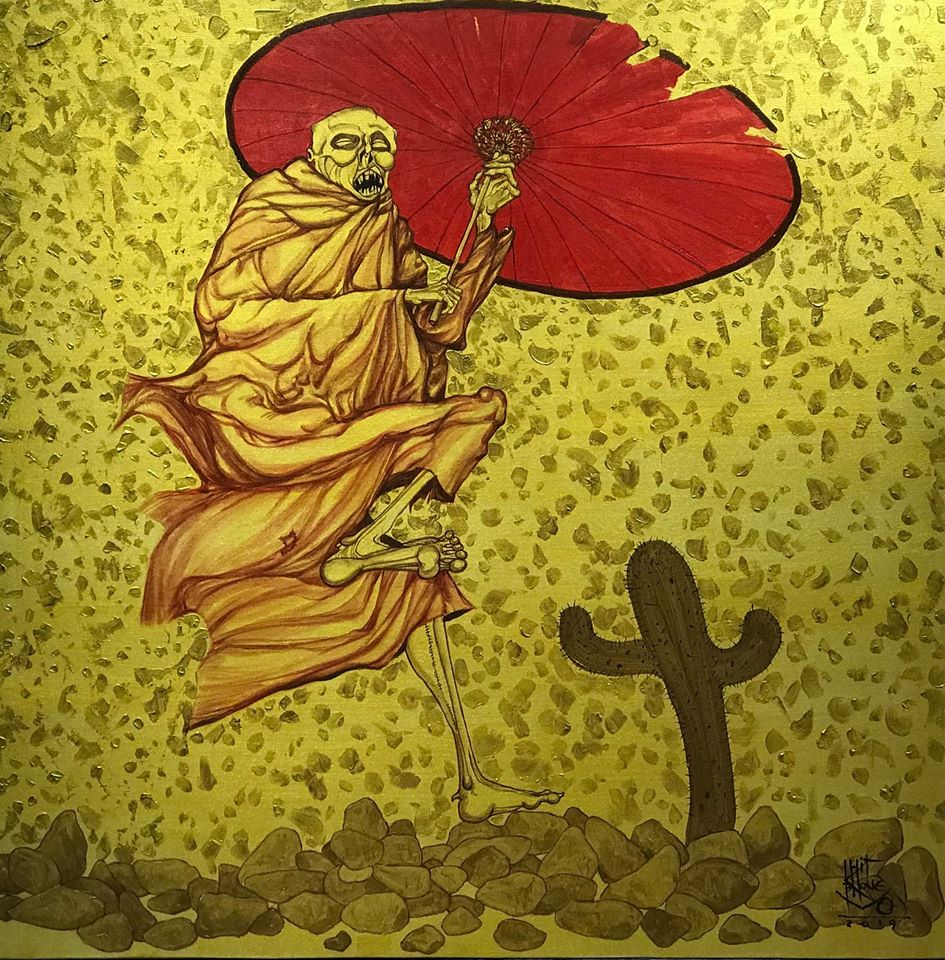

In the image adorning the wall of the CEO’s office in the Yangon Book Plaza, a young novice carrying a large food container follows a monk in a neat robe who is putting up a ragged and frayed umbrella. Both are striding so fast they could disappear out of view in a blink. They are also tilting their heads back, looking up to the gold-soaked firmament.

This spectacular serenity has long been identified with Buddhist art in Myanmar. But once the familiar flesh of the figures is stripped away, and their skeletal beauty is embraced, the painting can be reduced to a downright disgrace, even in the eyes of a monk. As San Mon Aung puts it, Khit Bhone Mo’s skeleton paintings can be “distasteful” to Burmese, who tend to seek utopia in art.

Maybe the fact that an art connoisseur like San Mon Aung has consistently collected only the artworks of late master Bagyi Aung Soe suggests that boundary pushers are a rare find in contemporary art in Myanmar. But when Khit Bhone Mo held his first solo exhibition, Deadly Rhyme, in 2017, San Mon Aung discovered that the artist had this “unusual” element. It seems that sometimes fate makes the great short-lived to punish mediocrities. On his 48th birthday on Oct. 20, Khit Bhone Mo departed this life on the same day he arrived.

That was exactly 13 days before his second solo exhibition, Saffron, which is organized by Yangon Book Plaza’s We Collection. All 16 paintings, evocative of the Saffron Revolution in Myanmar in 2007, feature skeleton monks. A gasping monk with many bullet holes in his skull puts up a ragged and frayed umbrella on which two pigeons are resting. A monk runs in a panic, spreading his battered robe like a wing. A boggle-eyed monk presses the left side of his skull with an umbrella clutched under his armpit.

Most relate Khit Bhone Mo’s morbid panache for mortality in his paintings with his deteriorating health over the last few years. He suffered from chronic heart problems and had a severe stroke, and had to visit the ICU several times for these and other illnesses, and have many surgeries. But, years before all of these commenced, his close friend L Minpyae Mon said, Khit Bhone Mo had often talked about his inspiration for painting skeleton monks.

Far from being morbid, the artist was well known for being annoyingly optimistic, prone to sudden bursts of laughter, and possessing a wicked sense of humor. As a wedding present, he once gave a friend a painting of skeleton musicians performing in a traditional Myanmar drum ensemble. If someone told him anything negative, he would say with a grin his signature line: “There is nothing to feel sad about in life—not even death.”

It seems that what Khin Bhone Mo truly captures in his paintings is a sense of time passing—whether fast or slowly. Be it a man in a battered cloak—in one painting in his Deadly Rhyme series—playing a wavy piano on a seemingly flowing bed of dry leaves; or the delicate yet frigid movement of a woman’s hands as she combs the hair of another skeleton woman. Sometimes, even when the figure is still, like that of a translucent skeleton monk sitting on a bench, unaffected by a bunch of ghoulish crows hovering around him, there is an urgent sense of action within him.

The anatomy of the skeleton seems to have ultimately enabled him to conjure this true living element of time, rather than death. Yet, Khin Bhone Mo had to go through fire and water to get to this artistic enlightenment. There were times things got so despondent for the artist that he had to take off the frames of his paintings and sell them to earn money—however little—when not a single piece sold. But even when he was so penniless he could not afford to buy paints and canvases, he alienated customers, who tended to bargain for his art—while the true art he fought for was not marketable.

According to his friends, there were only two things in his life—art and alcohol—and both seemed to take his life in the end. For such a maverick artist, there can be few places on Earth to take refuge. But the Deadly Rhymes and Saffron series put Khit Bhone Mo’s art in the company of the medieval French Danse Macabre paintings and the Spanish master Francisco de Goya’s Two Old Men Eating Soup.

In fact, San Mon Aung said, Khit Bhone Mo’s hopes for the Saffron exhibition are what kept him going as his illness advanced day after day. But death seemed to have a different script, in which Khit Bhone Mo would not live to see Saffron open. Despite this, his bodily sickness could never deter his hyperactive imagination.

In Deadly Rhyme, the musical notes the skeleton is playing are a mixture of three famous Myanmar traditional songs. Aye Myat Mon, the partner of Khit Bhone Mon, said they are Hmone Shwe Yi (Gorgeous Lady) and Hsaung Ami (In Time for Winter)—but she can’t remember the name of the last one.

In Saffron, Khit Bhone Mo hid his scarred identity somewhere. An observant viewer will see that the inner left legs of the monks in most paintings bear a long vertical rough stitch, running from right above the ankle almost up to the knee. To anyone who would think of this as a tragic episode, Khit Bhone Mo would probably say, “There is nothing to feel sad about in life—not even death.”

The “Saffron” exhibition is held at Yangon Book Plaza, Lamdaw, from Nov. 2-4.

Myint Myat Thu is a freelance journalist and cultural researcher, focused on the development of art economy and the Myanmar film industry.

You may also like these stories:

Myanmar Hosts First Major Art Auction

High-Definition da Vinci: Exhibition to Display Digital Versions of Leonardo Masterpieces